The sun wasn’t shining in Glasgow for COP26 and many in the solar sector lamented the lack of mention in countries’ pledges. Nonetheless, some vital announcements were made that will be crucial to the industry’s growth and its role in reaching net zero, writes Sean Rai-Roche.

It was billed as the last chance to save the world in the ‘decisive decade’ for climate change but COP26 did not result in the commitments that many activists, campaigners and climate vulnerable nations had hoped for. While there have been some positive multilateral organisations formed to tackle key emissions causes, countries’ individual commitments or Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), have not been enough to limit the world to 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming above pre-industrial levels.

Unlock unlimited access for 12 whole months of distinctive global analysis

Photovoltaics International is now included.

- Regular insight and analysis of the industry’s biggest developments

- In-depth interviews with the industry’s leading figures

- Unlimited digital access to the PV Tech Power journal catalogue

- Unlimited digital access to the Photovoltaics International journal catalogue

- Access to more than 1,000 technical papers

- Discounts on Solar Media’s portfolio of events, in-person and virtual

Analysis from renowned climate analysis group Climate Action Tracker (CAT) shows that under current national plans, the world would be headed for 2.4 degrees of warming, which climate scientists have said would be disastrous. While other analyses, including by the International Energy Agency (IEA), have said pledges could result in 1.8 or 1.9 degrees of warming, these place too much weight on net zero targets in the second half of this century, resulting in a more favourable outlook, says Taryn Fransen, an international climate change policy expert at the World Research Institute (WRI).

The draft text of the Glasgow Climate Pact called on all parties to “accelerate the development, deployment and dissemination of technologies, and the adoption of policies, to transition towards low-emission energy systems, including by rapidly scaling up the deployment of clean power generation and energy efficiency measures”.

If it wasn’t already, the role of renewables has been made abundantly clear. While this is no surprise to those of us in the solar industry, with energy consumption accounting for around 75% of global emissions according to the WRI, it does give our sector the ammunition and added urgency required to make an even more compelling case for the role of solar PV in decarbonising economies, protecting the natural environment and future proofing societies from the climate crisis.

So, what specific targets and policies have been set for renewable power generation and solar more specifically? Which countries have been the most ambitious when it comes to solar deployment? And what state support will there be to facilitate such deployment?

India pledges achievable, realistic targets

India entered COP26 as one of the countries to watch and it was likely it would transfer its domestic policy of reaching 450GW of renewable energy by 2030 into its NDC. This has essentially happened, with the country committing to 500GW of renewables by 2030, including nuclear and large-scale hydropower.

While its pledge to reach net zero by 2070 was received with disappointment in many quarters, it was never likely to be any sooner given the country’s historically low emissions and growth requirements, says Ulka Kelkar, director of the World Research Institute in India. Many analysts predict that 2070 is the earliest date India can reach net zero. Kelkar says that a net zero date had become a hotly contested debate in India and the fact that one was set was a positive.

On its 500GW target, “people don’t fully appreciate the scale of these targets,” says Kelkar, adding: “500GW by 2030 means India will have to install the UK’s total renewable capacity of 45GW every year, for 10 years”. While India has missed some of its short-term targets – it was planning on reaching 100GW of solar PV by next year, which it will almost certainly miss – it has witnessed a “spectacular rise” of solar PV, according to the IEA’s India Energy Outlook report, with this sure to continue under its current NDC.

But India’s domestic manufacturing capacity is not enough to meet its current climate goals, says Saon Ray, senior fellow at the Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations (ICRIER). In response, the country is eyeing a build out of PV manufacturing capacity, which it hopes will spur domestic deployment and protect itself from any market shocks. The head of India’s Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE), RK Singh, has openly stated the country’s desire to challenge China’s dominance in solar manufacturing.

“India needs to develop domestic solar manufacturing capacities and reduce its dependence on imports, which at present is close to 90%, of which 80% is imported from China, to avoid disruption in the future,” says Ray, adding that while this should help to scale up domestic manufacturing, imports will still rise in the short term until the basic customs duty is introduced next year. India also lacks access to certain key minerals needed in PV manufacturing and is trying to solve this via joint venture agreements, she adds.

Kelkar does notes that the other four pledges made by India during COP26 are ambitious and, if realised, would send a very strong signal about its attitude to decarbonisation. Other surprising 2030 targets include an absolute reduction in its emissions, achieving carbon intensity reduction of 45% over 2005 levels and sourcing 50% of energy requirement from renewables, although Kelkar says this last point has point has since been clarified by the Indian government to refer to installed capacity and not generation capacity.

India also launched the Green Grids Initiative-One Sun One World One Grid (GGI-OSOWOG or OSOWOG) transcontinental solar grid project at COP26, which aims to connect 140 countries through a “common grid” and will require the input of myriad governmental agencies and private companies.

India was, however, jointly responsible, along with China, for the last-minute watering down of language on coal, modifying the pacts wording to refer to a ‘phase down’ rather than ‘phase out’, much to the dismay of the majority of attending nations.

China sticks to its guns

On 29 October, just before COP26, China submitted its highly anticipated NDC that was branded ‘disappointing’ and ‘a missed opportunity’ by pundits. It was condemned by climate activists who said it represented little progress on its 2016 targets, despite massive reductions in the cost of clean energy.

While the targets contained in the new NDC are an improvement on the 2016 submission, they are no more ambitious than the objectives put forward by Chinese President Xi Jinping at the Climate Action Summit hosted in the UK last December.

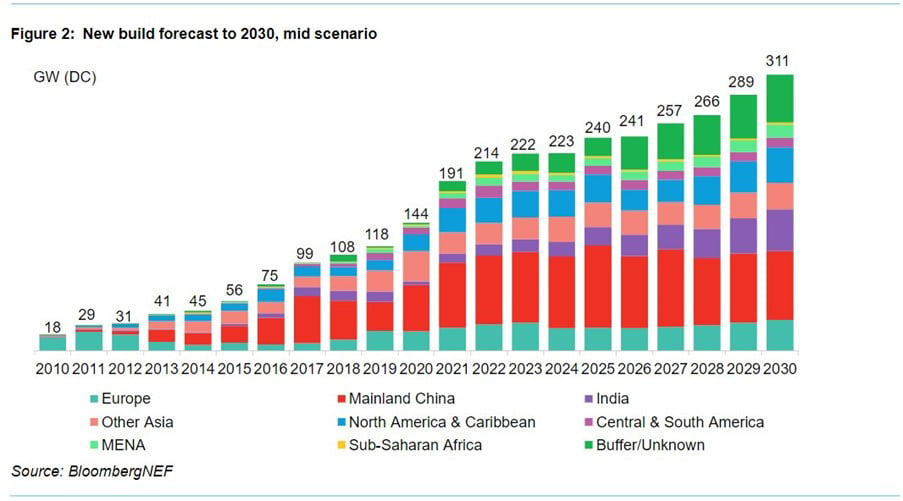

Nonetheless, China, which has over twice the capacity of solar PV than the US and Europe combined, has committed to 1.2TW of renewable capacity by 2030, more than double its current level of 535GW.

The country’s NDC also said it will lower its carbon intensity by more than 65% by 2030 from 2005 levels and increase its share of non-fossil fuels in its energy mix to around 25% by 2030.

“It wasn’t an update from what they announced in 2020,” says Ryan Wilson, a climate and energy policy analyst at CAT. “There has been a slight language change, so before China was going to peak emissions ‘around’ 2030 and now it is peak ‘before’ 2030 but apart from that not much has changed.”

“But 1.2TW of renewables is nothing to sniff at,” says Wilson. “It’s not bad across the board. China’s probably a good representation of how things have gone in general [at COP26] – there has been an incremental step up, but we’re past the point at which we can celebrate incremental increases. We need transformative commitments, and we didn’t get that from China.”

“And a lot of countries haven’t stepped up,” he adds.

Key COP26 climate targets set by major polluters

- China has committed to 1.2TW of renewables by 2030

- India has committed to 500GW of renewables by 2030

- The US has committed to deriving 80% of its electricity supply from renewables by 2030

- The UK has set a target of 100% renewable electricity by 2035

- Saudi Arabi, which was accused of obstructing climate progress, has refused to divest from oil and gas production

- Japan is to source around a third of its power from renewables and will cut its emissions by 46% by 2030 compared with 2013 levels.

- South Korea has pledged to cut its emissions by 40% by 2030, up from 26.3%, with 30% of power from renewables, up from 7% in 2020.

- The European Union has pledged to source 40% of its final energy demand from renewable sources.

- Russia did not strengthen its climate targets, rated ‘highly insufficient’ by CAT, and intends to reduce emission by 30% by 2030, based on 1990 levels.

The US arrives empty handed but acts as orchestrator

The US was hoping to ‘step up’ by arriving at COP26 with one of the largest infrastructure packages the world has ever seen, but President Biden’s Build Back Better bill is yet to be passed.

At the start of the month US lawmakers passed a US$1 trillion bipartisan infrastructure deal that will see the country’s power infrastructure modernised to support new renewables projects. But Congress is still at a deadlock regarding the US$1.75 trillion reconciliation package that includes nearly US$570 billion for tax credits for utility-scale and residential clean energy – including solar PV – as well as incentives to spur domestic PV manufacturing.

Speaking at the time of the announcement, US President Joe Biden called the bill the “most significant investment to deal with the climate crisis ever” and said it will position the country to achieve its target of a 50-52% emissions reduction by 2030.

But this bill has not yet been passed because of resistance from Democrat senators Manchin and Sinema, with rumours of the watering down of some areas, although the White House has reaffirmed the centrality of renewables to the bill.

And current infrastructure funding is by no means enough to get the US on track to meet its NDCs. “It’s not going to get us to the NDC by any stretch,” says Fransen, “so we’re really watching the reconciliation bill, which has, in its current version, very significant climate provisions”.

Nonetheless, the conference was not fruitless for the US, which joined the International Solar Alliance (ISA), took the lead on multilateral agreements on deforestation and methane and signed a joint agreement with China that, while thin on detail, agreed to cooperate on climate change more closely and was a positive step forward for the two powerhouses who have recently been embroiled in bitter political and trade disputes.

Source: See references (1)

South America shows progress

When it comes to South American countries, CAT rates most of their NDCs as ‘insufficient’ or ‘highly insufficient’ for keeping 1.5 degrees within reach. Countries currently with net zero commitments on the continent include Brazil, Colombia, Argentina, Uruguay, Peru and Costa Rica (government positions, but not legislated) and Chile (legislated), says James Ellis, BloombergNEF’s head of research in Latin America. “We can expect to see redoubled efforts to support the growth of solar and other sources of renewable energy,” he adds.

While specific policies under net zero pledges in South America have not been explained in full, Ellis says solar PV will play a “very significant” role is the continent’s decarbonisation. “Despite uneven support for it across the major markets of the region, solar has generally been growing the fastest of any source and its levelised cost of energy (LCOE) has been falling the most rapidly,” he explains.

“In many markets of Latin America, solar is and will continue to be the most competitive source of new bulk generation. This means of course that solar is an essential ingredient in the mix as countries, cities, companies and consumers across the region push to decarbonise.”

Ellis notes another few important policy announcements that were made by South American countries at COP26: Chile’s Ministry of Energy’s joint announcement with power company AES to increase battery energy storage capacity to 1,563MWh, many times what the country (or region) has today; Colombia’s announcement that it is to hold its next auction in 2022, “which will likely be important for solar,” says Ellis; news of Brazil’s hydrogen strategy being set for release next year; and Argentina’s agreement with Australian mining company Fortescue’s proposal to invest US$8.4 billion in a 2.2 million tonnes per year green hydrogen export project in Patagonia.

EU and the UK need to match words with action

In July, the EU pledged to reduce emissions by at least 55% by 2030, as part of its ‘Fit for 55’ policy, and to source 40% of its final energy demand from renewable sources. SolarPower Europe estimates this will require 660GW of solar power installed by 2030, amounting to 58GW installed each year.

New EU commitments at COP relevant to solar were few and far between but it did announce a ‘Just Energy Transition Partnership’ with South Africa – that will support South African decarbonisation of its electricity system – and the US$1 billion ‘EU-Catalyst partnership’ with Bill Gates and EIB President Werner Hoyer, which aims to boost investments in “critical climate technologies”.

While many individual states were critical of slow progress and watered-down language at the conference, the European Commission said the event had helped get the world closer to 1.5 degrees of warming.

The UK has some of the world’s strongest climate targets, but they are not necessarily backed up with funding or policies, says Wilson. The country has set a target of 100% renewable electricity and has pledged to reduce its emissions by at least 78% by 2035, compared to 1990 levels, along with its net zero by 2050 target.

To do so, it has earmarked around US$1.34 billion to support the electrification of UK vehicles, US$2.02 billion for net zero research and innovation and US$5.24 billion for the decarbonisation of homes and buildings. At COP26, UK chancellor Rishi Sunak also told companies and financial institutions in the City of London to submit public plans on how the world’s largest financial centre aims to reach net zero in line with the UK’s 2050 commitments.

“The policies and spending brought forward in the Net Zero Strategy mean that since the [UK’s] ‘Ten Point Plan’, we have mobilised £26 billion (US$35 billion) of government capital investment for the green industrial revolution,” says the UK government.

However, Wilson says the current spending and policy commitments in the UK do not match up with their targets and more funding needs to be made available for the country to have any chance of achieving such lofty commitments.

Another shot in Egypt

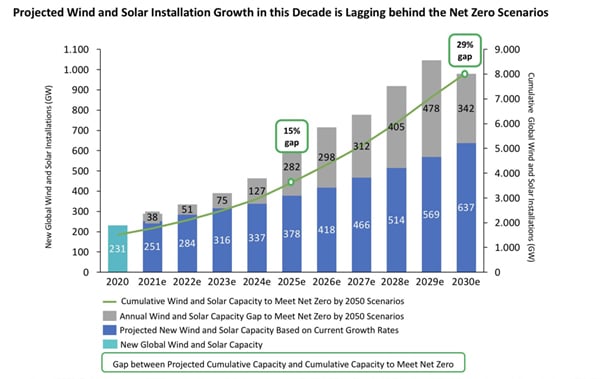

Despite the many positive, promising pledges made at COP26, there was an overwhelming feeling that not enough had been achieved at this seismic conference. Current commitments still put us on a trajectory of 2.4 degrees of warming and there were not enough mentions of the role of solar, one of climate change’s biggest adversaries, at the two-week event.

The lack of progress has been so acute that many, including the architects of the landmark 2015 Paris Agreement, called for countries to submit further upgraded plans at the next summit, COP27, which will take place in Egypt. This will now happen. But that is a year away and a lot can happen, or not happen, in a year.

Key COP26 announcements

- Global Renewable Energy Alliance (GREA) formed by Global Solar Council (GSC) and Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC).

- More than 100 world leaders, including Brazil, pledged to end deforestation by 2030.

- The Global Methane Pledge aims to limit methane emissions by 30% compared with 2020 levels.

- The world’s two biggest emitter, the US and China, sign commitment to enhance climate action in the 2020s

- US joins International Solar Alliance (ISA)

- OSOWOG initiative launched

- The Global Energy Alliance launched a US$10.5 Billion fund for emerging economies

- Over 40 countries promised to phase out coal

- Financial entities with assets totalling US$130 trillion agreed to back “clean” technologies, such as solar, and direct finance away from fossil fuel industries.

References

(1) Source: GWEC Market Intelligence, SolarPower Europe GMO 2021, IEA Net Zero by 2050 Roadmap (2021). Projected new wind capacity from 2021-2030 is based on GWEC’s Q1 2021 Global Market Outlook; projected new wind capacity from 2026-2030 assumes a ~4% CAGR, same as the projected CAGR from 2021-2025; projected new solar capacity from 2021-2030 is based on SolarPower Europe’s Global Market Outlook; projects new solar capacity from 2026-2030 assumes a ~14% CAGR, same as the projected CAGR from 2021-2025; Capacity gap figures are estimations based on the IEA Roadmap milestone for 2030. This data represents new and cumulative capacity and does not account for decommissioned projects.