The global market for clean energy technologies will exceed US$2 trillion by 2035, bringing it near parity with the global crude oil market today. Simultaneously, global supply chains will become more expansive than ever, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA).

Figures in the ‘Energy Technology Perspectives 2024’ (ETP-24) report from the IEA show that the global market for solar PV, wind power, battery energy storage systems (BESS), electric vehicles, electrolysers and heat pumps will almost triple over the next ten years.

Unlock unlimited access for 12 whole months of distinctive global analysis

Photovoltaics International is now included.

- Regular insight and analysis of the industry’s biggest developments

- In-depth interviews with the industry’s leading figures

- Unlimited digital access to the PV Tech Power journal catalogue

- Unlimited digital access to the Photovoltaics International journal catalogue

- Access to more than 1,000 technical papers

- Discounts on Solar Media’s portfolio of events, in-person and virtual

At the same time, international trade in renewable energy technologies will more than triple to US$575 billion—more than 50% larger than the trade in natural gas today.

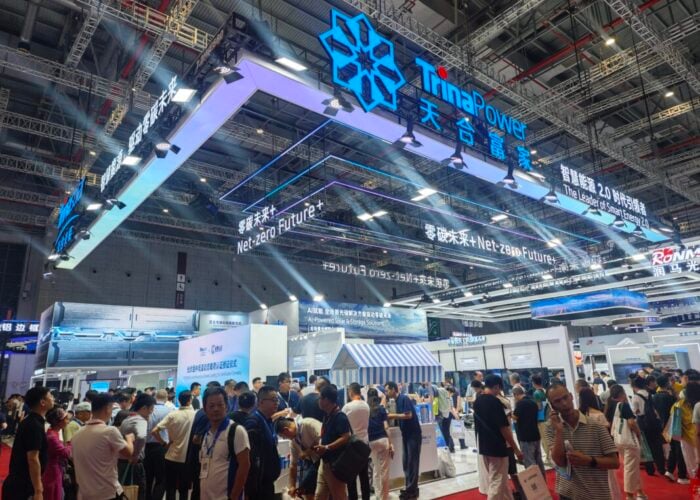

Today, global renewable energy technology supply chains are overwhelmingly concentrated in China. More than 90% of the supply of solar PV products, for example, is based in China, for all parts of the supply chain except for modules.

That will continue in 2035, the ETP-24 report said. Based on current policies, China’s clean energy exports will exceed US$340 billion by 2035, roughly the equivalent of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates’ oil export revenues for 2024. This level of growth over a comparatively short period – compared with oil markets – illustrates the “pace” of growth that the IEA expects for the global clean energy industry.

Shipping concerns

International trade in renewable energy technologies like solar modules and batteries is significantly more efficient than fossil fuel shipping, the IEA said.

“A single journey by a large container ship filled with solar PV modules can provide the means to produce as much electricity as would be generated from the natural gas onboard more than 50 large liquefied natural gas (LNG) tankers, or from coal onboard 100 large ships,” the report said.

This is mostly because solar modules can be installed and then produce reliable energy for years, rather than being used up like oil or gas.

Today, around half of all maritime trade in clean energy technologies passes through the Strait of Malacca, which connects the Indian and Pacific Oceans. The report said that this is a “significantly” higher concentration than the roughly 20% of maritime fossil fuel shipments which pass through the Strait of Hormuz, between the Gulf of Oman and the Persian Gulf.

The IEA report said: “The dependency on maritime chokepoints poses risks to supply chain resilience worth monitoring, especially since the average clean technology cargo is more than ten times the value of the average fossil fuel cargo per tonne.”

PV Tech previously reported on the potential impact that Houthi attacks from Yemen on ships in the Red Sea could have on international solar supply.

‘Tensions and trade-offs’

As global trade becomes more important for energy markets increasingly relying on renewable energy technologies, centralised supply in China and an over-reliance on a small number of shipping lanes could pose supply and security problems. IEA executive director Fatih Birol said that clean energy markets and policies are subject to “tensions and trade-offs” between affordable and timely deployments and secure supply chains.

In response to supply chain insecurities and the market dominance of Chinese companies, countries including India and the US have implemented trade barriers and tariffs to try and spur domestic manufacturing investment.

India’s basic customs duty (BCD) and approved list of models and manufacturers (ALMM) legislation imposed taxes on solar imports and limited the suppliers that are allowed access to much of the market. In 2022-23, India experienced a significant module supply shortage, as the incentives for domestic production were not strong enough to outweigh the restrictions on incoming supply. In 2023, the government had to suspend the ALMM to bring the country closer to meeting its solar deployment targets.

The US has recently been engaged in a second round of antidumping and countervailing duty (AD/CVD) tariff investigations, which seek to put tariffs on solar cells and modules imported from Southeast Asia, in an apparent effort to support domestic US manufacturing against “unfair” competition.

Both countries have recently seen significant manufacturing expansions, for solar PV in particular, but arguments are split over whether they have been driven by trade defences or the robust incentives both governments have put in place.

Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump has spoken of plans to increase tariffs to replace income taxes as part of his largely protectionist policy proposal. He has previously said: “Tariff is a beautiful word.”

Birol said: “Even as countries have a chance to tap the benefits of clean energy transitions for their citizens, ETP-2024 finds a need for global perspective and cooperation in pursuit of industrial and trade strategies that can ensure widespread prosperity and help keep international energy and climate goals within reach.”

The full IEA ETP-2024 report can be read here. It also covers the role that emerging economies can play in the global energy transition and the global policy and trade landscape for renewable energy technologies.