Off the back of a report stating that US solar assets are not meeting performance expectations across all segments, one of the authors has told PV Tech Premium that this risks damage to the industry’s reputation in the long term if, as a result, equity investors in PV projects do not see their return profiles being realised several years down the line.

San Francisco-based data analytics and insurtech firm kWh Analytics’ most recent annual Solar Generation Index gave an overview of field observations in US solar, showing persistence in asset underperformance.

Unlock unlimited access for 12 whole months of distinctive global analysis

Photovoltaics International is now included.

- Regular insight and analysis of the industry’s biggest developments

- In-depth interviews with the industry’s leading figures

- Unlimited digital access to the PV Tech Power journal catalogue

- Unlimited digital access to the Photovoltaics International journal catalogue

- Access to more than 1,000 technical papers

- Discounts on Solar Media’s portfolio of events, in-person and virtual

There are a number of hypotheses for why this trend is happening, says Jason Kaminsky, CEO of kWh Analytics. The foremost is that, up until recently, there has been a lack of historical data for running models about future performance.

The second is that optimistic PV project performance estimates that make financial models look better are attractive for asset buyers looking to raise capital from lenders, tax equity providers and equity investors.

“If you’re trying to buy or finance an asset, you need to believe the numbers in order for your financing to work,” adds Kaminsky. “So, it’s the incentive structures. I don’t think anyone is acting with bad intent, but in some weird ways people are maybe more comfortable with higher numbers that support their return forecasts.”

The third hypothesis is that forecasts tend to focus on module performance, but in the field, the biggest loss of production is typically inverter availability. Most models are assuming 99% inverter availability, but last year, data from US operations and maintenance (O&M) specialist NovaSource, said availability was closer to 96%, although this percentage can rise after the first few years of operation. Meanwhile, 60% of overall lost energy from PV projects was due to inverters.

Kaminsky noted that 2022 did not see major fires, with wildfire smoke on the west coast becoming a typical cause of underperformance. Given geopolitical events and supply chain issues, nowadays it takes longer to fix broken equipment than it did in the past where sourcing spare parts is necessary.

“All of those don’t necessarily get baked into a model but are real issues that the operators are trying to address,” adds Kaminsky.

Module degradation is underestimated

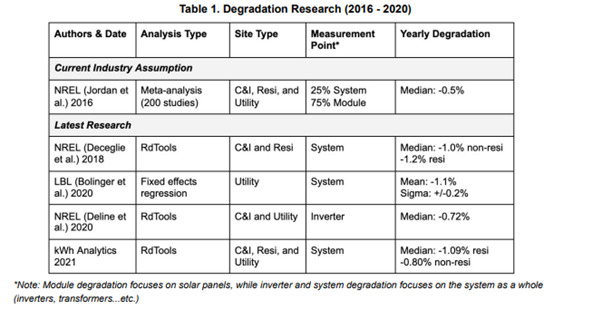

kWh Analytics did a study funded by the US Department of Energy on degradation and found 0.8% median annual degradation for non-residential assets. This is similar to research by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory that consistently shows between 0.75% to 1% degradation in system performance per year, whereas most financial models are still forecasting just 0.5% degradation. Over time, this will result in a divergence between what’s happening in the field versus what most stakeholders are estimating.

The degradation findings were summarised in a table from kWh Analytics’ 2021 Solar Risk Assessment below:

Overconfident estimations

Investors are typically evaluating the revenue streams from solar projects to support their economic assumptions, so higher production figures can support higher asset valuations.

“If you’re putting together financing, you want to put together a set of assumptions that you think are going to give you an adequate return for the capital that you’re deploying, and a developer’s optimistic assumptions can be pervasive throughout the entire financial model,” says Kaminsky. “Production forecasting is a component of what you’re looking at and it’s not hard to think that you’re going to be a better operator, or that your availability is going to be perfect.”

He noted that it also takes a while for assumptions to change. For example, the industry has worked off half a percent degradation since Kaminsky joined it 15 years ago and it continues to do so despite evidence suggesting otherwise. The same goes with the 99% inverter availability forecasts.

Field observations can take time to be relayed back up the chain because developers are typically developing a project and selling it or handing it over to an asset manager, so some of the underperformance statistics get buried in the data, says Kaminsky, adding: “It’s easy to come at this with good intentions and still have a quite aggressive number.”

Again, Kaminsky says that he does not think industry players are deliberately putting out numbers that they don’t think they will hit, but there’s a risk that the industry wakes up and realises the assets aren’t performing in the way they’re supposed to be.

“In a world of higher interest rates, the capital has to be more judicious and focused on the return and focused on the assumptions,” he says. “With the Inflation Reduction Act here in the US, some of the solar facilities are going to be financed with the production tax credit. In that world, your returns are even more sensitive to production, because you don’t have the investment tax credit anymore. You’re getting your tax credits based off production.”

For 2023, Kaminsky takes hope in the emergence of new data usage in the sector and a trend of carrying out validation studies on the models being used, as happened in the wind industry two decades ago. The sector has to be honest with itself to start with when looking at data. Companies are beginning to try and improve, asking questions about minute fluctuations in sunlight, availability issues and the quality of estimations.

Long-term reputation damage

Due to how projects are financed and the way revenue from power sales gets eaten up by O&M and debt, a percentage hit on project performance can have a much larger percentage impact on the overall return on investment.

“The long-term risk that catches up to us is that you’re going to have equity investors that are looking to deploy capital and realising, three-to-five years down the line, that the return that you would expect from the long-term stable cash flows is not being realised,” says Kaminsky. “That has much more longer-term damaging effects to us as an industry if we’re not credibly providing the returns to people that they anticipate.”

The same trend historically in the wind sector had led to a reckoning driven by the tax equity community; however, Kaminsky noted that “tax equity and debt are probably a little bit more protected in solar than they were in wind, but the equity is much more exposed”.

In conclusion, Kaminsky says that the PV sector is growing rapidly and is expected to double in the next five years and so it is important as more professional investors come into the market that the current industry acts as “appropriate stewards of the capital” to avoid setting itself up for a big surprise in the capital markets.

“It’s not always news that people want to hear,” he adds, “but wind has been through this, and it’s fine, it came out the other end, and the PV sector will weather this as well. We just think it’s important that we can use the data as a growing industry to help inform our decision-making and financing strategies.”