OCI Holdings’ decision this week to buy a Vietnamese solar wafer facility to supply the US solar cell manufacturing industry makes clear the biggest vulnerability facing the sector today.

Korean chemical giant OCI bought a 65% majority stake in a 2.7GW silicon wafer facility in Vietnam this week, currently being built by Elite Solar Power. The company said it would be supplying wafers that meet US Foreign Entity of Concern (FEOC) requirements to the market by “early 2026”.

Try Premium for just $1

- Full premium access for the first month at only $1

- Converts to an annual rate after 30 days unless cancelled

- Cancel anytime during the trial period

Premium Benefits

- Expert industry analysis and interviews

- Digital access to PV Tech Power journal

- Exclusive event discounts

Or get the full Premium subscription right away

Or continue reading this article for free

The move, which an industry expert told PV Tech Premium would likely be the first of numerous wafer facility acquisitions in Southeast Asia, speaks to the strategic importance of reliable wafer supply for the US solar manufacturing industry.

The US needs solar wafers

Next year is set to see an expansion in US domestic solar cell capacity. Manufacturers T1 Energy, Talon PV, Hanwha Qcells and Mission Solar (a subsidiary of OCI) are all slated to start new cell production in 2026, which will significantly increase the roughly 2GW of operational cell capacity currently in the US.

But there is newfound pressure on the inputs for those cell facilities. From 1 January 2026, FEOC restrictions prohibit the use of any components from China or companies with significant Chinese financial backing. Chinese companies overwhelmingly dominate global production of solar wafers, ingots and polysilicon.

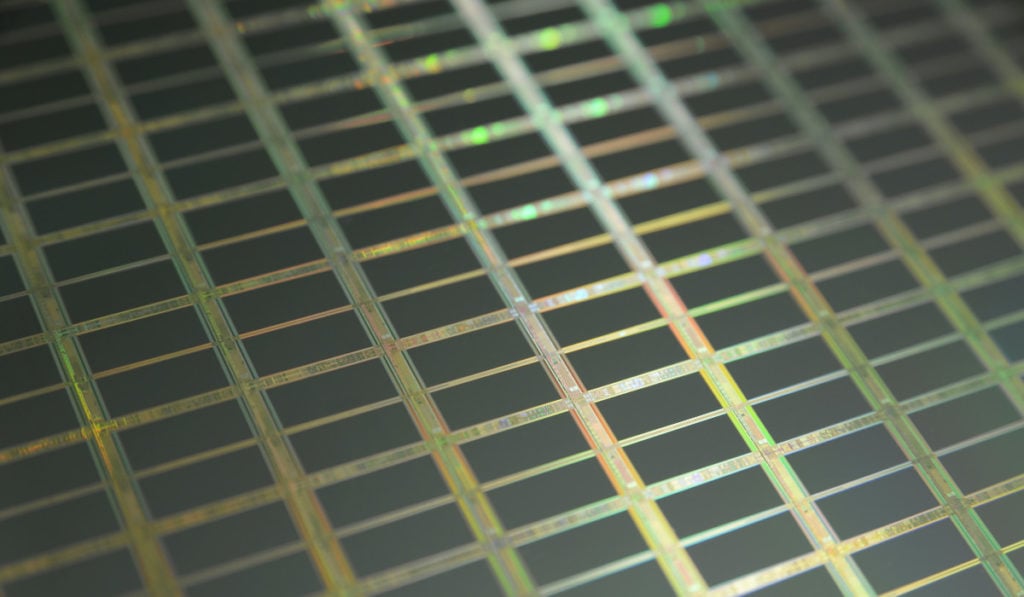

Wafers will be the essential chokepoint for US solar supply as cell capacity comes online. US solar producers have long needed bespoke supply chains to avoid trade barriers with China, but the FEOC regulations passed in the “One Big, Beautiful Bill Act” in the summer go further and are more restrictive than previous rules.

Reporting from the RE+ trade show last month, PV Tech heard that, thanks to FEOC and other restrictions like the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA), supply chain transparency and security are paramount for manufacturers and buyers alike.

It makes sense for non-FEOC companies to buy wafer capacity to supply reliable products to the US, given that meaningful domestic wafer capacity isn’t around the corner. US cell producers have an increasingly premium offering in the domestic market, given the pressures on imports from the antidumping and countervailing duty (AD/CVD), UFLPA and FEOC and the vast disparity between domestic module production capacity and domestic cell output, as shown in the graph below.

Major tier-1 Chinese manufacturers, such as LONGi and Jinko, have wafer and ingot capacity in Southeast Asia, which was built explicitly to supply the US market but has now been rendered defunct, partially by (AD/CVD) tariffs on solar imports from the region in tandem with FEOC.

In this light, OCI’s acquisition of Elite Solar’s wafer plant is a smart move. But the timing is surprising, given that most of the US industry is waiting for the other shoe to drop on the government’s Section 232 tariff investigation into polysilicon “and its derivatives”.

There is an argument to say that OCI is better off with the wafer facility than without it, regardless of the outcome of Section 232. The company told PV Tech that its wafers would supply “a range of customers, including our affiliate Mission Solar Energy, as well as other partners.”

Korean companies are likely to be hit particularly hard by the potential Section 232 tariffs, given the prominence of firms like Hanwha, which owns Qcells and is set to become the largest silicon solar manufacturer in the US, and OCI itself, which owns Mission Solar and has a polysilicon supply deal in place with Hanwha Qcells.

The Korean government has petitioned the US for a “flexible” approach to polysilicon tariffs on its products, warning that severe levies could affect its investments in US manufacturing.

Section 232 tariffs

Earlier this year, a report from energy analysts Wood Mackenzie said that Section 232 could be the “biggest supply vulnerability” for US solar and could “choke the entire market”. Depending on the final ruling, it could be a hammer blow to upstream US solar supply, affecting imports of polysilicon, silicon ingots, wafers and cells.

The Coalition for a Prosperous America (CPA) has proposed a Tariff-Rate Quota (TRQ) in its support for Section 232 tariffs, which was discussed at last week’s PV CellTech USA event, held in San Francisco. This would mean that a set amount of solar-grade polysilicon, wafers and cells would be allowed into the US each year before the tariff was applied; a practice which already features in other types of tariffs.

While only a proposal, PV Tech has heard that at least one major US market analyst is treating the CPA quota as a rough base case in forecasting for the Section 232 outcome.

The CPA—a bipartisan body representing US manufacturing—proposes applying a TRQ to Germany and South Korea, as “trusted allies” of the US, for their polysilicon, ingot, wafer and cell imports. But neither country has wafer or ingot capacity.

It is currently unclear whether other countries, like Malaysia, where OCI has polysilicon capacity, or Vietnam, where it just bought a wafer plant, could be included in the TRQ scheme. If they were, OCI’s purchase would look very astute, as favourable tariff conditions for a given country would increase the value of any wafer production facilities located there. But it’s likely that US producers will lobby against including countries with meaningful wafer or polysilicon capacity in a potential TRQ.

Most of the industry is still waiting for the chips to fall on Section 232. Once they do, we might see more non-Chinese firms follow OCI’s lead and move the non-FEOC supply chain one link further.