Solar modules manufactured in countries such as the United States, India and Laos display some of the highest defect rates, according to PV quality assurance provider Kiwa PI Berlin.

In a webinar yesterday discussing its recently published ‘2025 PV Module Manufacturing Quality Report’, experts from Kiwa PI Berlin offered insights into changing patterns in PV module quality worldwide.

Unlock unlimited access for 12 whole months of distinctive global analysis

Photovoltaics International is now included.

- Regular insight and analysis of the industry’s biggest developments

- In-depth interviews with the industry’s leading figures

- Unlimited digital access to the PV Tech Power journal catalogue

- Unlimited digital access to the Photovoltaics International journal catalogue

- Access to more than 1,000 technical papers

- Discounts on Solar Media’s portfolio of events, in-person and virtual

One notable finding was that countries that have seen a rapid recent ramp in manufacturing capacity have struggled with quality control, as revealed by higher defect rates.

“This can be attributed to the rapid increase in manufacturing capacity over the past year, which has created a challenge in quality control, operational stability and workforce training,” said Matthew Lu, vice president of Kiwa PI Berlin’s global factory service.

Countries including China, Indonesia, Vietnam and Turkey, on the other hand, report only “moderate” defect rates, reflecting their more “stable” operations, Lu said. Others, such as Thailand, Cambodia and Malaysia, also showed relatively low defect rates given their “robust quality protocols and efficient supply chains”.

“So, actually [this] shows how experience and infrastructure maturity affect defect rates, and also why it’s so important to stabilise operations as new capacities are added,” he said.

The most common defects

Based on data from its quality assurance and factory inspection activities wordlwide, Kiwa said 40% of defects were related to cell processing and soldering. The ratio of these findings has increased due to the introduction of new cell and module technologies.

Looking more closely, Lu said cell defects specifically accounted for 22% of the total. “This has been the industry’s most consistent and long-standing challenge over the past decades,” he said.

The most prevalent cell-level issue was metallisation, accounting for 39% of all cell defects. “This has become particularly problematic with the industrialisation of TOPCon cells, where metallisation-related issues frequently arise during production,” Lu explained.

“Then another significant concern is cell cracks, which represent a serious challenge in both cell quality and process control. In fact, cracks can greatly affect the structural integrity of the cells, compromising the overall reliability and performance of the modules,” he added.

To address these issues, Lu said the solution was to put enhanced quality control measures and additional factory audits to extend the quality insurance to the cell production facilities.

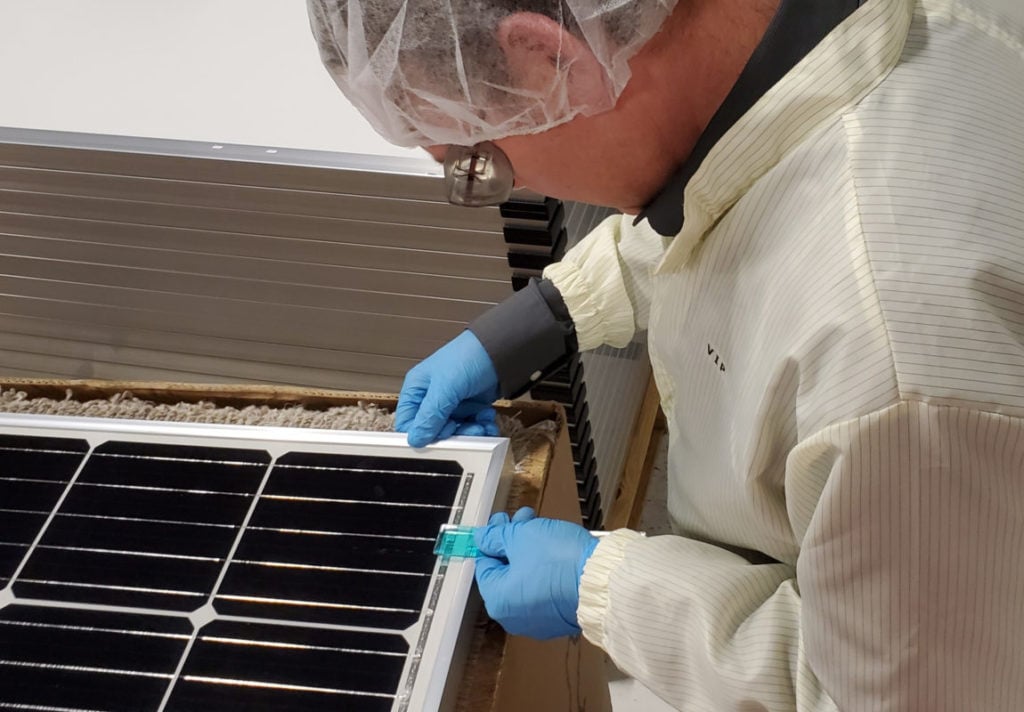

Frame damage had “surprisingly” become the second most common defect category, Lu said, accounting for 17.82% of the total. Kiwa PI Belin said the recent high level of module breakage in the field was possibly linked to frame damage, which was itself a consequence of the increasing size of solar modules.

“Our hypothesis is that the issues with the framing machine, process control and the sealant application are being impacted by the increasing size of the modules,” Lu said.

Glass damage was another issue of growing importance for the industry, one, again, most likely linked to the increasing size of modules. “Scratches or bubbles on the glass can weaken its mechanical strength and also significantly increase the likelihood of the breakage in the field, so this defect poses a serious risk to the long-term durability of the modules, especially in extreme weather conditions,” he said.

‘Whack-a-mole’

Don Cowan, Kiwa PI Berlin’s director of sales and marketing, highlighted how over the past decade, the overall module quality picture has fluctuated in step with the appearance of new technologies.

“In 2016 the industry achieved a fairly low defect rate, largely due to the maturity of polycrystalline modules. With the increasing shift towards monocrystalline, in 2017 and 2018, there were different changes in materials, processes and different production equipment. These advancements drove technological progress, which, of course, is great news, but they did introduce different quality training challenges and bumped up some of those defect rates.

“Moving into 2019, monocrystalline technology became more refined, and defect rates started to slightly decline. But in 2020, we had the influence of really large wafers, multi-busbar technology, increased module sizes and, of course, the various challenges posed by the pandemic and supply chain shortages.

“In 2021 and 2022, we saw those rates start to stabilise; some improvements in manufacturing automation, implementation of advanced quality control measures, such as wider adoption of automated soldering and also in-line defects detection systems. Most recently, 2023-24, the industry faced challenges arising from many shifting policies, increased requirements for supply chain traceability and the expansion of manufacturing into really new regions.”

Cowan said the industry had “essentially been playing ‘whack-a-mole’ when it comes to managing quality and constant change over the years”.

“Therefore, as the industry evolves, it’s really key for buyers and anyone in ther procurement process to stay the course, when it comes to managing quality with their suppliers. This really is an essential part of the current process,” he concluded.