Governments should focus on mini-grids as a means to enabling access to reliable electricity for hundreds of millions of people that don’t yet have it and mini-grids using solar and batteries have matured as a technology class, but financing such projects remains problematic, a new report has found.

Around 789 million people worldwide still do not have access to electricity, which is the seventh of the international Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) adopted in 2015 at the UN Sustainable Development Summit. The new report, from the Sustainable Energy For All organisation launched by the UN in 2011 in partnership with Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF), argues that mini-grids are often the lowest cost means of providing access, from extensive research of Sub-Saharan Africa, Asia and small island nations, with case studies of existing projects in six countries.

Unlock unlimited access for 12 whole months of distinctive global analysis

Photovoltaics International is now included.

- Regular insight and analysis of the industry’s biggest developments

- In-depth interviews with the industry’s leading figures

- Unlimited digital access to the PV Tech Power journal catalogue

- Unlimited digital access to the Photovoltaics International journal catalogue

- Access to more than 1,000 technical papers

- Discounts on Solar Media’s portfolio of events, in-person and virtual

To meet the challenge of SDG7, around 238 million households in those regions would need access to electricity by 2030. The report’s authors found that around 111 million households could be electrified in 10 years at a cost of around US$128 billion, with the estimated cost of electricity from solar hybrid mini-grids set at around US$0.49 to US$0.68 per kWh today.

Mini-grids can be a far cheaper and faster alternative to building out the grid to rural or isolated areas, and from around 60 solar and solar hybrid (usually solar with battery storage) in 2010 in the regions assessed, there were more than 2,000 by the end of February this year. Around 60% of those mini-grids are in Asia, and the majority use solar with batteries. At the moment, about two-thirds of those are lead acid batteries and about a third lithium-ion, but according to the report the uptake of lithium-ion is increasing as a proportion.

Contrast with large-scale renewables

However, the mini-grid and rural electrification space has not benefited from the same economies of scale and policy support that have been a huge enabling factor for large-scale and grid-connected renewables, which often come with long-term off taker contracts or have been supported by subsidies of either initial cost or operating expenditure.

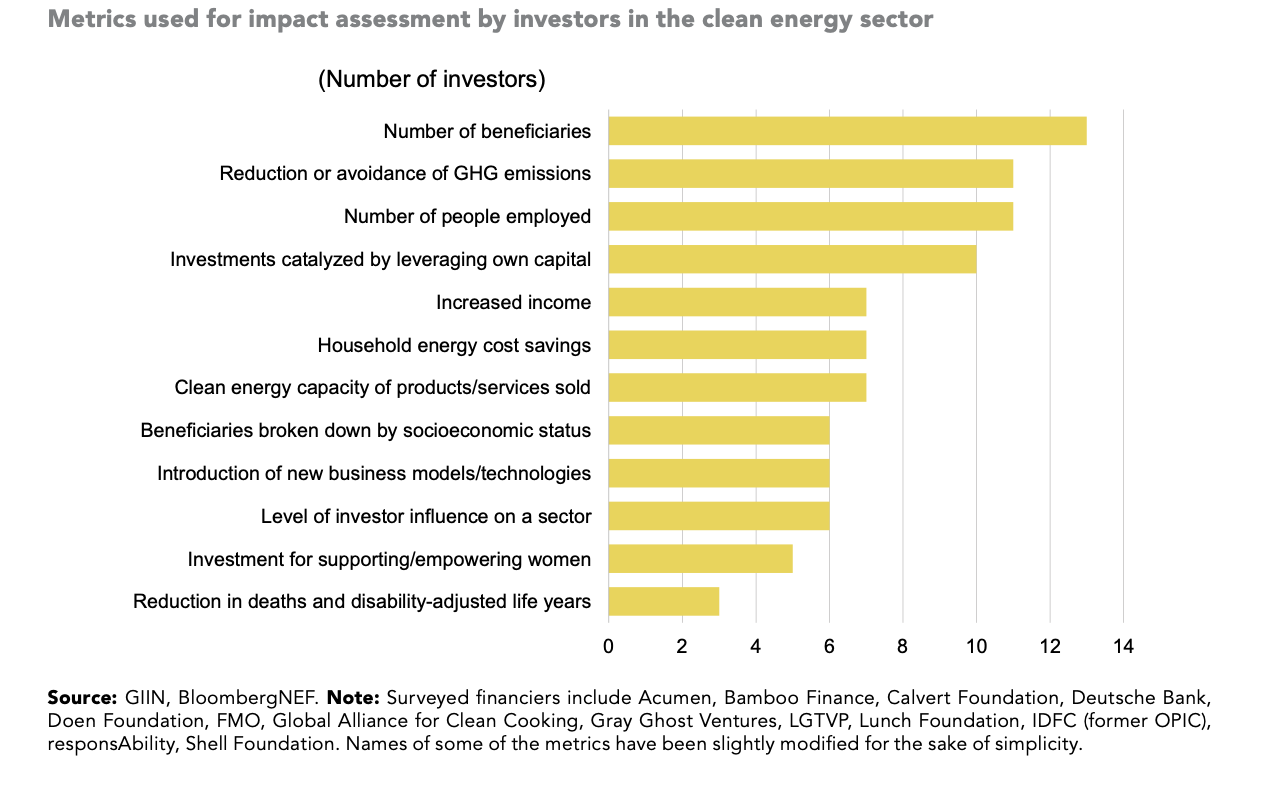

It is much more difficult for investors to gain long-term visibility into returns as well as the impact their financing will have on mini-grids and the sector is yet to achieve a “tipping point at which it can expand exponentially without subsidised support”, the report said.

Another barrier is that mini-grids tend to be between around 10kW to 100kW generation capacity, sometimes becoming bigger and reaching megawatt-scale if serving whole communities. By contrast, bulk renewables projects tend to start out at around 1MW and can go up to 1,000MW, offering a chance to do the larger deals that private financiers tend to favour, since they can amortise transaction-related costs over bigger volumes of capital. One answer to this could be aggregated portfolio investments in mini-grids.

There can be policy enablers at government level, BNEF and Sustainable Energy for All said, including direct financial support. There are many potential mechanisms for this, but results-based financing (RBF) – where financing is paid out at stages contingent on success – is generally preferred to full payment upfront when a project is first started out.

Industry stakeholders can also take steps, the authors wrote, with one big barrier at the moment a lack of data, especially data that proves and compares the impact that mini-grids can have on communities, quality of life and economics, not to mention the potential revenues that can be generated.

Some electrification programmes and companies offering access to electricity also emphasise economic empowerment of their customer communities such as enabling them to start businesses using their power, while other developers might ensure that a planned mini-grid has an industrial off-taker customer as well as households.

In short, the report argues that while there is a challenge ahead, supportive policy frameworks, maturing industry practises and technological awareness as well as visibility of impact for investors and development funders could make a big difference in providing electricity access in line with the world’s goals on sustainable development. Despite the barriers, the market continues to grow, with more than 5,000 projects underway counted by the report's authors and it was also noted that while it was previously the domain of mostly small companies and NGOs, a wider range of stakeholders are becoming involved in the mini-grid space including major legacy power sector players.