Following a surge in solar glass imports from China and Vietnam, Indian glass manufacturer Borosil launched an investigation into unfair dumping practices last year. According to Pradeep Kheruka, Borosil chairman, glass imports skyrocketed to 9,000 tonnes per day, more than three times the annual manufacturing capacity of Indian companies, prompting immediate action by the government.

The move followed on from the Indian Director General of Trade Remedies (DGTR), a part of the Ministry of Commerce, recommending the imposition of preliminary antidumping measures on solar glass imports in November 2024.

Unlock unlimited access for 12 whole months of distinctive global analysis

Photovoltaics International is now included.

- Regular insight and analysis of the industry’s biggest developments

- In-depth interviews with the industry’s leading figures

- Unlimited digital access to the PV Tech Power journal catalogue

- Unlimited digital access to the Photovoltaics International journal catalogue

- Access to more than 1,000 technical papers

- Discounts on Solar Media’s portfolio of events, in-person and virtual

While waiting for the outcome of a hearing with stakeholders, PV Tech Premium spoke to Kheruka about the numbers and how a ministry communication error may have impacted media reports.

The Ministry of Finance’s decision to impose provisional duties is aimed at curbing what Kheruka describes as a “tsunami of imports”. The duty provides interim relief while a more detailed investigation is conducted. A public hearing followed on 20 December last year, allowing stakeholders across the ecosystem – including module manufacturers and customers – to present their views.

After evaluating all input, the Ministry will issue a final recommendation to the Ministry of Finance, which has up to 90 days to take further action. The provisional duty stems from concerns over predatory pricing by exporters.

Kheruka claims that Chinese exporters, whose prices were oscillating up and down by just 10% over the last three years, have now reduced their prices by 40% in less than a year. This price, he says, barely covers the cost of raw materials, and perhaps some power and fuel. Other production costs, labour, depreciation and finance costs are not covered in their selling price. He also claims that there have been no significant input cost changes in the industry ecosystem that could account for this 40% drop in prices.

“It’s very clearly a predatory matter,” he adds. “They want to dominate the world solar manufacturing capacity.”

Impact of the duties

The antidumping duties aim to bridge the price gap between domestic and imported solar glass. Domestic solar glass producers have welcomed the decision, as it provides a level playing field for India’s burgeoning solar glass manufacturing sector. However, India’s module manufacturers have expressed concerns about the increased costs they may have to face by importing glass from Vietnam and China.

A reference price has been announced; the antidumping duty will be calculated as the difference between the total import price – which shall include the cost, insurance and freight (CIF) price – plus 10% Basic Customs Duty and the reference price. As a result, the import cost should always reach the reference price.

Miscommunication initially clouded the rollout. The first notification from the Ministry of Finance erroneously equated the reference price with the duty, sparking backlash from developers over the perceived additional costs. This led to swift amendments, with the Ministry issuing a corrigendum within 24 hours to clarify the situation.

Based on the first Ministry release, articles appeared in the press citing unnamed developers’ rough calculations that price hikes could be as high as INR1-2.5/Wp (US$0.012-0.029/Wp) for imports from China. However, to counteract these claims, Borosil publicly issued its own rough calculations based on the corrected Ministry figures. It found that the duty on average would be INR0.48/Wp for conventional modules with backsheets, and INR0.63/Wp for glass-glass modules.

However, Pranav Master, senior practice leader and director of Crisil Research, says that on the basis of his teams interaction with the industry, the overall impacts would be higher, at roughly INR1-1.10/Wp.

Challenges for Indian solar glass producers

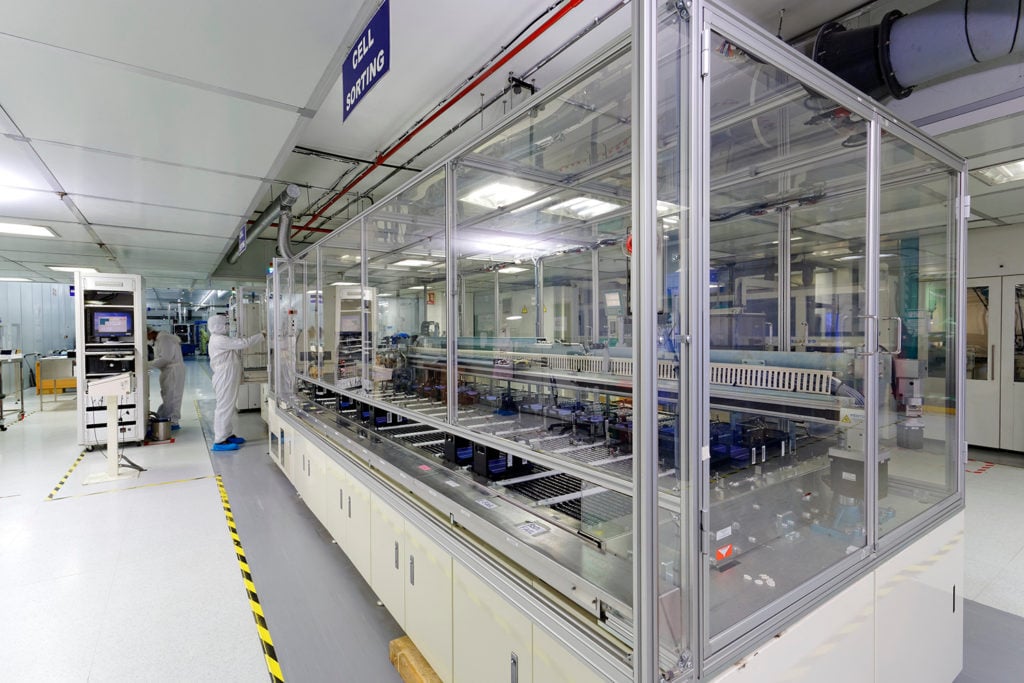

This uncertainty over production prices comes at a time where India’s solar glass production capacity has grown substantially, with six manufacturers now collectively producing 2,300 tonnes per day (equivalent to 16GW of modules), of which Borosil Renewables accounts for 1,000 tonnes. This marks a significant leap from 2022 when Borosil was the only operational domestic player.

Nonetheless, local demand, which is driven by an expanding solar module industry projected to exceed 24GW this year, outstrips supply, keeping imports from China necessary despite the duties.

The extra costs on these imports, which Kheruka believes can be easily absorbed by the larger ecosystem, are weighed against the benefit of creating viable conditions for more Indian manufacturers to start producing solar glass domestically.

“We have enough skilled manpower, capital, land and raw material,” says Kheruka. “We can make it domestically, so there’s no reason for us to import it and India really needs the jobs.”

Solar glass is a specialised material critical to PV modules, with high transparency and low iron requirements. Its strategic importance makes the global solar glass market a focal point for competition. Kheruka claims that through predatory pricing, Chinese manufacturers have already “completely demolished” solar glass industries in Europe.

At the end of last year, India further strengthened its domestic PV manufacturing support with the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) confirming it will include solar cells in its approved list of models and manufacturers (ALMM) legislation from June 2026.