At the COP28 summit in Dubai late last year, 118 countries, excluding China and India, signed the ‘Global Renewables and Energy Efficiency Pledge’ to triple global renewable energy capacity to 11TW by 2030.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) published the report Renewables 2023 in January 2024, stating that the current growth trajectory would enable global renewables capacity to increase to 2.5 times its current level by 2030 under current policies and market conditions, surpassing 9TW.

Unlock unlimited access for 12 whole months of distinctive global analysis

Photovoltaics International is now included.

- Regular insight and analysis of the industry’s biggest developments

- In-depth interviews with the industry’s leading figures

- Unlimited digital access to the PV Tech Power journal catalogue

- Unlimited digital access to the Photovoltaics International journal catalogue

- Access to more than 1,000 technical papers

- Discounts on Solar Media’s portfolio of events, in-person and virtual

However, the study also mentions four challenges that could prevent countries from reaching the 11TW target by 2030, including policy uncertainties and delayed policy responses to the new macroeconomic environment; insufficient investment in grid infrastructure; cumbersome administrative barriers, permitting procedures and social acceptance issues; and insufficient financing in emerging and developing economies.

Grid connection queues

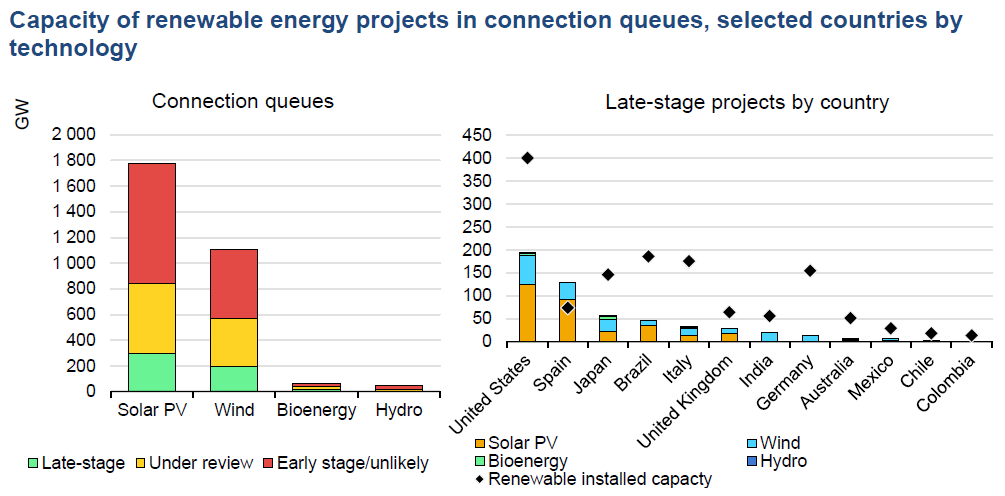

Collectively, nearly 3TW of solar PV, wind, hydropower and bioenergy capacity are waiting to connect to the grid in the US, Spain, Brazil, Italy, Japan, the UK, Germany, Australia, Mexico, Chile, India and Colombia, according to IEA. About 1.5TW of this capacity lies in wind and solar projects in advanced stages, with a connection agreement in place or under active review. That’s equivalent to five times the capacity additions of solar PV and wind in 2022.

A third of these solar and wind projects (500GW) have either signed connection agreements or are in the final stages of this process. They will likely connect the grid in the next five years. The remaining 1TW of projects are under active connection review to determine their viability and the required grid upgrades.

However, another 1.5TW of projects are still in early-stage development and less likely to become operational in the medium term. These projects may only represent an early expression of interest and may also require additional feasibility studies.

Solar projects account for more than half of the capacity waiting to connect to the grid. Totally, about 1.8TW of solar PV projects are in connection queues, with more than half of them in early stages or unlikely to be built.

Potential causes of delay

The development of grid infrastructure usually goes through three phases: scoping, permitting and construction. Delays frequently take place in each phase, especially for high-voltage interconnections.

During scoping, grid developers may have difficulties in securing funds, obtaining the land, and incompatibility with local conditions such as soil and the environment. In the permitting process, developers could face complex procedures and a lack of personnel. Even after receiving permits to build the infrastructure, they may encounter successful appeals against the project that cause further delays.

Public opposition and changing legislation could also take place during scoping and permitting.

After both steps, developers may also face supply chain constraints, shortages of skilled workers, difficulties in accessing the site and further technical difficulties.

Investment Growth

According to the IEA, global spending on power grid infrastructure has remained stable for many years. Annually, investments in grid infrastructure reach US$300 billion, hovering at about US$300 annually. However, the spending is focused on grid upgrade and replacement rather than expansion.

Additionally, the majority of investments are concentrated in advanced economies and China, underpinned by the need to address grid balancing requirements in power systems that are increasingly reliant on renewables.

Alex Whitworth, vice president and head of Asia Pacific power research at Wood Mackenzie, says: “Not all countries have under-invested in the grid. China’s annual grid investments have surged 60% over the last decade, and this has supported lower curtailment and allowed China to take the lead in renewable energy deployment globally.”

Wood Mackenzie’s How China became the global renewables leader report states that China has budgeted US$455 billion in grid investments from 2021-2025, up 60% from a decade before. Moreover, it deploys long-distance transmission lines of more than 1,000 kilometres to support over 100GW of renewables development in remote inland areas.

Aside from the concentration of investments in China and advanced economies, planning, permitting and completing a new grid infrastructure could take up to 15 years, compared with one to five years for new renewables projects.

“In many countries, this poses a significant risk of being derailed before completion,” Whitworth says.

To ensure the completion of grid infrastructure projects, IEA suggests: “Robust stakeholder and public engagement is key to inform scenario development. The public needs to be aware and informed about the link between grids and successful energy transitions.”

Looking ahead, IEA says grid investment needs to nearly double by 2030 to over US$600 billion per year, with an emphasis on digitalising and modernising distribution grids.

However, the most important barriers to grid development vary by region. For example, the financial health of utilities is a central challenge in India, Indonesia and South Korea. Access to finance and high cost of capital are the main barriers in many emerging markets and developing economies, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa. In Europe and the US, the most substantial obstacles lie in public acceptance of new projects and the need for regulatory reform.

“To support transition to a high variable renewables grid, there will need to be either a major increase in government support for grid and storage or a difficult and expensive reform to create new revenue mechanisms for these critical assets,” says Whitworth.