The price of shipping containers from Asia to Europe and North America remains high but should start to fall in the new year, although material price drops won’t occur in earnest until 2023 when new capacity is brought online.

That additional capacity, however, may be offset by new International Maritime Organisation (IMO) rules to address the industry’s emissions.

Unlock unlimited access for 12 whole months of distinctive global analysis

Photovoltaics International is now included.

- Regular insight and analysis of the industry’s biggest developments

- In-depth interviews with the industry’s leading figures

- Unlimited digital access to the PV Tech Power journal catalogue

- Unlimited digital access to the Photovoltaics International journal catalogue

- Access to more than 1,000 technical papers

- Discounts on Solar Media’s portfolio of events, in-person and virtual

That was the view of industry experts who attended a UK Parliamentary Committee on International Trade as well as shipping analysts PV Tech Premium spoke to on the issue.

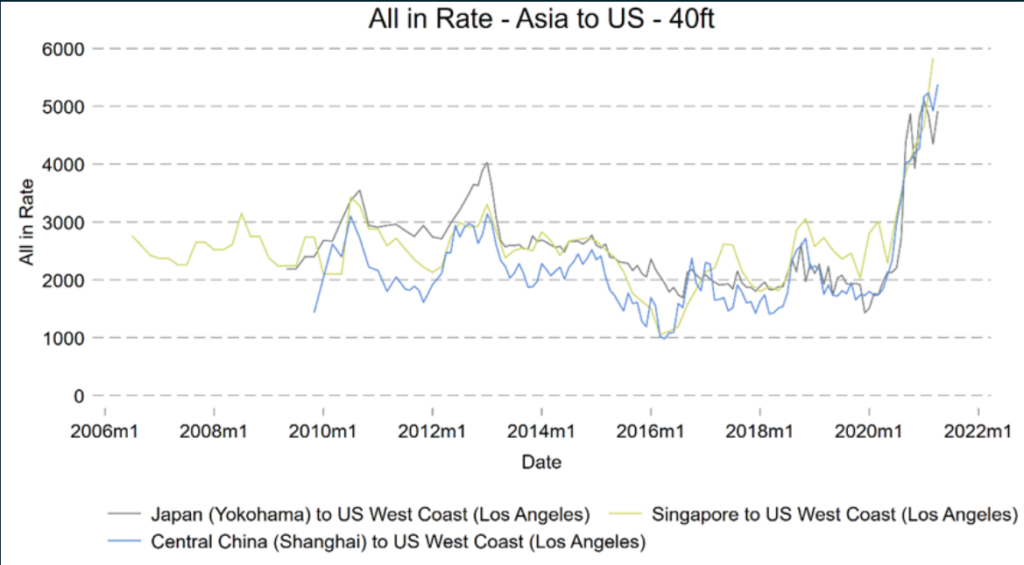

Spot rates for containers from Asia to Europe are up around 366% in a year, according to Michelle Wiese Bockmann, markets editor at Lloyd’s List who gave evidence to the parliamentary committee. Longer term contracts for the same route were up by around 465%, she added. This has placed upward pressure on modules prices shipped from China to the US and Europe.

Meanwhile, the cost of leasing vessels and hiring charter vessels has soared lockstep with traditional container line prices. Bockmann said the industry was paying five times more for a “clapped-out” old ship than it was a year ago, while short distance charter vessels were charging US$250,000, up from US$25,000 last year.

The state of play was similar last time PV Tech Premium gave a shipping update but, importantly, Bockmann said that long term contracts being negotiated now were also 400% higher than they were a year ago.

George Griffiths, global pricing specialist at S&P Global Platts, said this could be read in two ways. Either the sustained high prices could be a signal that shipping companies don’t expect prices to come down anytime soon or they predict that upcoming capacity additions will drive down prices and therefore want to lock in lucrative contracts.

While there is some ambiguity about the extent to which prices will drop in 2022, the industry is certain that a substantial amount of extra capacity is to come online in 2023, resulting in lower prices. According to Bockmann, 270 new vessels are set to come online in 2023. Griffith believed it could be higher than that – closer to 400 perhaps – but added that at least an additional 20% of the capacity of the current global fleet is scheduled to come online.

That said, such capacity additions may be offset by new regulations affecting sea freight that are being brought in by the IMO in an attempt to lower carbon emissions from the shipping industry, which currently accounts for 3% of global emissions.

One crucial part of these new regulations is taxing older, more polluting ships, with the money used for carbon offsetting schemes. The industry will likely respond by reducing the speed of some of its older vessels, rather than scrap them, which would in turn reduce emissions. However, this would also lead to slower turnaround times for deliveries, congest waterways and therefore limit the impact of those 2023 capacity additions, said Griffiths.

“New international regulations coming out in 2023 may see the sailing speed of some vessels reduced in order to meet emission standards, which again can lead to less capacity because you have more ships on the same route sailing,” explained Bockmann, adding that the precise balance between speed reductions and the scrapping of older vessels was unknown.

In short, 2022 doesn’t look any rosier when it comes to shipping costs. Prices should start to come down, but the real drops won’t be for another year. Companies trying to lock in long term contracts are between a rock and a hard place: ensure supply or get overcharged as prices do come down. And even short-term chartered vessels are charging astronomical rates.

Both Griffith and Bockmann pointed to a bleak past decade for the shipping industry, with some companies turning loses year after year. They said container liners are forecast to make US$250 billion profit this year alone after years of loses, meaning there is very little appetite for change, and prices certainly won’t come down to pre-Covid levels for a very long time, if at all.