In August, the Georgia Public Service Commission (PSC) approved the 2025 Integrated Resource Plan (IRP) submitted by local utility Georgia Power, which sets out a framework for the state’s energy mix for the next decade.

While the IRP includes a number of positive components for the clean energy transition – including plans to install 4GW of new renewable power capacity by 2035 – Georgia Power plans to meet some of the growing electricity demand in the state with fossil fuel projects. These include upgrades to a natural gas plant near Savannah, and the expansion of the Vogtle nuclear plant, leading to an IRP that balances components of renewable power and fossil fuels.

Try Premium for just $1

- Full premium access for the first month at only $1

- Converts to an annual rate after 30 days unless cancelled

- Cancel anytime during the trial period

Premium Benefits

- Expert industry analysis and interviews

- Digital access to PV Tech Power journal

- Exclusive event discounts

Or get the full Premium subscription right away

Or continue reading this article for free

However, when asked if this IRP is the sort of robust middle ground that could help set a precedent for effectively transitioning from fossil fuel-dominated resource plans to ones that rely on renewable energy, Sean Garren, chief programs officer at advocacy group Vote Solar, tells PV Tech Premium that, “you’re probably being a little generous to the Georgia Power IRP.”

“This IRP, in general, is skewed so heavily towards fossil fuels and locking us into further dependence on fossil fuels and their unpredictable prices and market dynamics,” he continues. “I think the reality is that the gigawatts of renewable capacity in Georgia Power’s latest IRP are simply an admission that renewable energy is the only technical path forward – or at least a critical piece of the only technical path forward – to serving the growing demand for energy in the US.”

This shift towards greater reliance on fossil fuels in state IRPs is present across the US; when asked about the state of IRPs in the US at present, a spokesperson from think tank RMI says that more states are expecting to use more fossil fuels in the coming years.

“Utility resource plans now include 53GW more gas capacity than wind and solar capacity in 2035,” says the spokesperson. “This is a stark contrast to our Q2 2024 IRP review, in which planned wind and solar capacity in 2035 were nearly equivalent to planned gas capacity.”

With many utilities incentivised by market dynamics and their own business models to support fossil fuel developments, rather than renewable and distributed energy projects, questions remain as to how solar and storage projects can be better integrated into state IRPs in the future.

Practical considerations

An obvious question to come out of Georgia Power’s decision is why support fossil fuel plants at a time where the energy transition is more urgent than ever? To an extent, there is an increasing demand for electricity to meet – figures from RMI show that utilities that updated their IRPs in the second quarter of this year plan to increase project load by 2% through 2035 to meet growing electricity demand – and commissioning as much new power generating capacity from as many sources as possible is a route to meeting this demand.

However, the RMI spokesperson tells PV Tech Premium that the financial argument in favour of fossil fuels is less compelling than ever.

“With demand for gas turbines reaching new heights and tariffs further threatening international supply chains, costs for new gas plants are soaring,” says the spokesperson. “We see that the cost assumptions used in planning are growing year-over-year, and exceeding the levels commonly assumed in industry benchmark studies.”

The spokesperson notes that Duke Indiana’s latest cost estimates for its Cayuga combined-cycle gas plant, for instance, are 36% higher than in previous years’ resource plans. This translates to an US$900 million increase over planned costs for just one fossil fuel plant in the state.

“We know that there’s a multi-year waitlist for new gas turbines, that the waiting time to build out new fossil gas infrastructure to deliver gas to plants is really long and constrained,” adds Garren, highlighting administrative delays associated with fossil fuel plants.

As a result, Garren says that the combination of fossil fuel unattractiveness and the low levelised cost of electricity (LCOE) for solar means that large-scale solar deployment is the only viable option to meet growing electricity demand.

“Solar-plus-energy storage [and] solar-plus-wind, and energy efficiency and demand-side management – where you’re controlling customer demand at certain points – is getting to the place where it provides reliable 24-hour power,” says Garren.

“With that reality, and layering on the economics of solar being so cheap, as compared to any other energy resource, really, you are going to win in any open-source competition, for essentially any type of energy you need.”

Perhaps most strikingly, he suggests that utilities such as Georgia Power are actively working against these trends and the very spirit of competition by continuing to include fossil fuels in their IRPs.

“That is something that the Georgia Power IRP skews away from, open competition, because they want to put their finger on the scale for fossil generation.”

Shifting responsibility from the federal to state governments

With the impracticalities of fossil fuel plants clear, particularly in relation to solar projects, Garren suggests that the political climate of the US is driving utilities towards an otherwise surprising level of support for fossil fuel projects.

“This is an example of what we’re seeing nationwide, unfortunately, that is particularly in Republican-led states, there is a lot of political pressure to support expansion of fossil fuels and increased dependence on fossil fuels, flowing from this federal administration on down to the state level,” he says.

Much of this stems from the president himself, whose “drill, baby, drill” rhetoric has led to significant policy shifts to disadvantage clean energy projects, most notably in the form of shortened timelines for projects to receive tax credits once guaranteed by the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA).

Even without this federal-level political context, the RMI spokesperson notes that regulatory frameworks often used by utilities are “a barrier to building the smarter, cleaner, more affordable systems,” suggesting that there are administrative delays, as well as political ones, to shifting to a greater reliance on renewable energy in state-level IRPs.

However, Garren notes that this situation grants individual states greater responsibility for setting their own energy agendas, and while this has proven damaging to the clean energy transition in Georgia, there are examples of other states whose IRPs encourage a greater reliance on clean power.

“If you look at a place like Texas, which is largely skewed towards very open-source [energy generation] – ‘whatever resource can provide what we need, we’ll go with that’ – we’re talking about the fastest-growing renewable energy market in the country,” he explains, calling Texas a “shining example” of how a state government can embrace a technology-agnostic approach to energy policy, and one where the more favourable economics of renewable energy in general, and solar in particular, are evident.

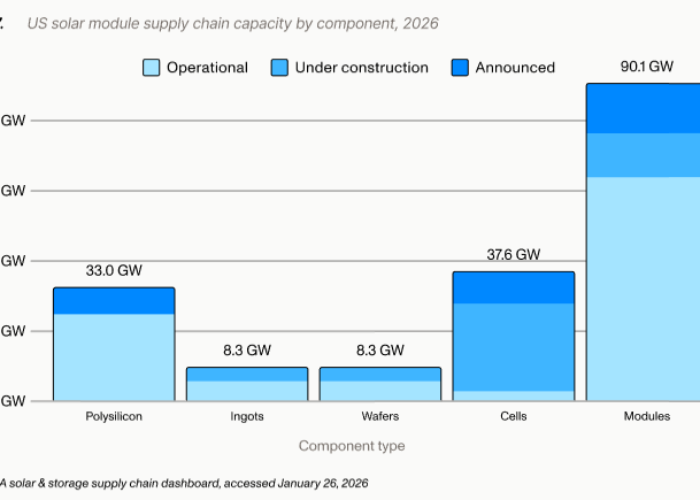

Indeed, Texas’ commitment to its solar sector is well-known, boasting the most new solar capacity additions among the US states in 2024. The Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA) expects the addition of a staggering 37.6GW of new solar capacity in the next five years – again the most in the US – and notes that close to US$60 billion has been invested in the state’s solar sector.

Steps towards the next IRP

Garren suggests that much of the reluctance to include more renewable power in a state’s IRP comes from the risk associated with tinkering with an energy mix that has, historically, relied heavily on fossil fuels.

“There’s a certain risk to doing something that feels new and innovative, like building a programme that uses 100 local solar projects instead of one massive gas plant, and I think that decision-makers are nervous about taking risks at a time in which they know that people’s bills are going to go up,” he says, suggesting that fear of being blamed for rising bill prices is affecting utilities’ decision-making.

“Even if it was a way to save people money, the challenge is you’re so afraid of getting blamed for rising rates that you tend to be reticent to take risks,” Garren ads.

However, he also suggests that the business model used by a number of utilities does not necessarily align with greater renewable energy deployment. A single centralised grid system, where a single operator is responsible for, and profiting from, grid expansion and project approval, is fundamentally different to, say several residential solar-plus-storage systems providing power generation and grid-balancing services, each on a much smaller scale.

“The reality is that building lots of big wires to connect these projects [and] investing in fossil generation that you’re going to operate for the rest of its life are all part of the utility business model that make them a great deal of money,” says Garren.

“Running a more efficient system that needs less wires [and] involves more private customers and developers that are offering different, innovative solutions is an exciting future for us as ratepayers, but it’s a daunting future for utilities that have a very cushy business model now, and are not interested in changing it.”

This has been particularly evident in California in recent weeks, where the California Solar and Storage Association (CALSSA) has called for fines to be levied against two utilities operating in the state for not reaching approval decisions on solar and storage projects within their targeted timeframes.

Speaking at the time, Kevin Luo, policy and market development manager for CALSSA, suggested that the utilities’ business models are so threatened by the growing storage industry, in particular, in California that they see local storage projects as a direct competitor to their commercial interests, and that they are able to “get away with suppressing what they consider to be their competition”.

Ultimately, with states granted more autonomy in setting their energy policies, separating those states’ utilities from older business models that incentivise fossil fuel deployment, and reforming grids to make better use of renewable and distributed energy sources, could yield positive results in the future.