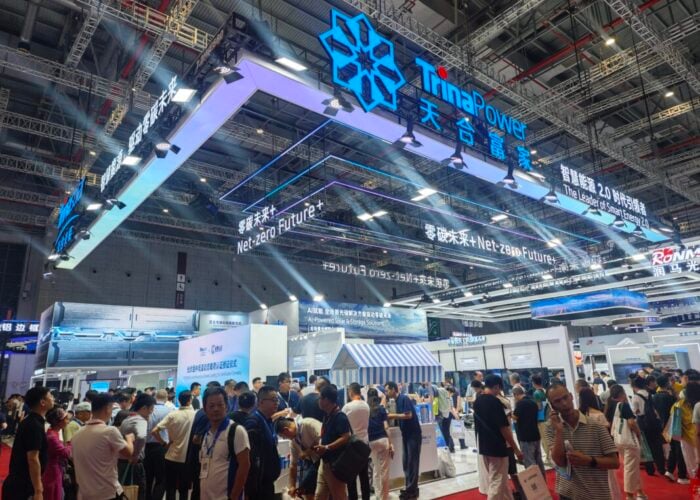

Having just finished three days in Shanghai at the SNEC event in China, one is left with much to ponder over, with regards the state of the global solar industry in the middle of 2016. And looking at all the drivers and leading indicators that emerged from the meetings, talks and events, it is clear that the solar PV industry today has moved into an altogether different paradigm, and one that can possibly be characterised by three somewhat competing business related activities.

In this two-part blog, I will seek to explain what this solar PV world of three parts looks like today, how this has come about, and what the implications of this could be to the industry in the next 12-18 months.

Unlock unlimited access for 12 whole months of distinctive global analysis

Photovoltaics International is now included.

- Regular insight and analysis of the industry’s biggest developments

- In-depth interviews with the industry’s leading figures

- Unlimited digital access to the PV Tech Power journal catalogue

- Unlimited digital access to the Photovoltaics International journal catalogue

- Access to more than 1,000 technical papers

- Discounts on Solar Media’s portfolio of events, in-person and virtual

China solar part 2 – what happened next after Europe & trade wars

On a very broad level, the solar industry now has two parts: China and non-China. And while one could argue this has been the case for the past decade, there are several factors today that make this far more important with knock-on effects to the supply of components to any global PV end-market.

Right now, China is both the largest producer of solar silicon wafers (by some margin) and has the largest end-market globally. Indeed, on the second issue here, it is amazing how we have the largest solar end-market being sized and governed by ‘allowed’ capacity additions that by the middle of the year have yet to be sanctioned by Beijing. On the low side, annual figures of 16-18GW were being brandished: at the upper end, figures as high as 25GW were being touted.

But it is the dual thrust of silicon solar wafer supply (at the 80% level) and end-market size dominance that sets out the top-level split of China and non-China dynamics at play in the sector.

The other factor that then comes into play is one that has emerged post-European market dominance (where China modules were shipped to Europe in droves), and a few years into the trade-war climate that effectively controls the way Chinese (and Taiwanese) cell and module components can be exported to both the US and Europe.

All things considered we now have 3 elements of the solar PV industry today that have to be considered as somewhat sub-segments of the overall solar PV industry, but that effectively have their own supply and demand (and capacity related) dynamics.

The following sections of the blog seek to outline these, how they came about, and how they may play out going forward. Lastly, I will provide a hint of what this means for capex, expansions and technology, each of which is directly linked to the companies operating within the three different segments.

Made-in-China; bought-by-China; installed-in-China

It was the holy grail of politicians and lobbyists the world over, that would justify incentives and stimulate local employment and indigenous economic growth: establish (through FiTs or similar) a government backed local end-market for solar deployment, backed up by a thriving local domestic upstream manufacturing base, that in turn creates jobs and stimulates research activity down through the academic community.

Not the unique model for solar by any means, such aspirations have constantly been voiced by politicians and lobbyists alike when rolling out solar roadmaps for any individual country. Until now, no country has succeeded, or come close to this. In fact, almost the opposite could be seen in the way the manufacturing (or attempts to create this) have largely failed across Europe and the US in the past decade.

So, as we digest the Chinese market in May 2016, we are confronted by China that has an almost 100% supply consumption to what is the largest end-market in the world today. Here however, we have a situation that has developed largely by default, not by intention, and has been shaped by market and political forces outside the country that have largely led to the artificial market-cap levels being set on an annual basis out of Beijing.

But regardless of the factors that caused this, this is what we have today. And in many respects, it is not what China intended, as it is no secret that China’s solar PV aspirations for manufacturing were intended to put the country in pole position on a global scale, not simply having to artificially control domestic demand to justify sustaining manufacturing that was meant to be driving export levels.

The result of this is that we have two types of solar PV manufactures in China. One falls into the sub-header of this section: made-in-China; bought-by-China; installed-in-China.

Having participated in the deluge of European PV exhibitions during 2005 to 2010 that characterised the first wave of Chinese exports to Germany, Italy and other subsidy-rich European end-markets of the time, I remember being amazed at seeing so many new Chinese cell and module producers appear by the dozen each time a new Intersolar or PVSEC exhibition was held in Europe.

Fast-forward Europe just a couple of years to 2012, and about 80% of these Chinese producers were gone from the market, and at the time, even China spoke about having a domestic manufacturing segment in which just ten or so key players would be allowed to continue (or as was the case, be prioritised for finances needed to expand or continue operations).

Briefly, many thought this was happening. Some of these zombie operations at the time would be consumed by leading Chinese players to easily add capacity (mostly at the wafer to module stages) with a bare minimum of capex showing on the books.

However, in the past three days at SNEC, the halls were again thriving with almost exactly the same companies that a decade ago had been left on the scrapheap when Europe introduced trade restrictions while at the same time seeing its market share decline rapidly.

This time though, many of these companies have just one role to play in the industry – supplying local end-market demand, something that was blatantly clear from the total lack of English-based marketing collateral on show at some pretty large booths.

As such, this forms the first segment of the industry to consider from a manufacturing perspective, with no shortage of GW cell and module producers whose output is a mix of in-house branded, OEM supply or contracted production, but ultimately is being consumed domestically.

“Having participated in the deluge of European PV exhibitions during 2005 to 2010 that characterised the first wave of Chinese exports to Germany, Italy and other subsidy-rich European end-markets of the time, I remember being amazed at seeing so many new Chinese cell and module producers appear by the dozen each time a new Intersolar or PVSEC exhibition was held in Europe.

Fast-forward Europe just a couple of years to 2012, and about 80% of these Chinese producers were gone from the market, and at the time, even China spoke about having a domestic manufacturing segment in which just ten or so key players would be allowed to continue (or as was the case, be prioritised for finances needed to expand or continue operations).”