Some of the BRICS nations are witnessing a shortfall of billions of dollars in the renewables investment required to meet climate change mitigation policies, according to a report from the Institute of Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA).

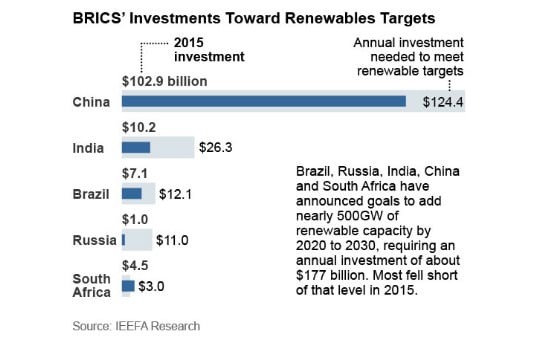

A total of US$130 billion was invested in renewable energy development in these countries last year, but combined the four countries – Brazil, Russia, India and China – require a total of US$177 billion invested annually. Collectively the BRICS nations aim to install 498GW of renewables capacity over various time horizons ranging from 2020-2030.

Try Premium for just $1

- Full premium access for the first month at only $1

- Converts to an annual rate after 30 days unless cancelled

- Cancel anytime during the trial period

Premium Benefits

- Expert industry analysis and interviews

- Digital access to PV Tech Power journal

- Exclusive event discounts

Or get the full Premium subscription right away

Or continue reading this article for free

IEEFA has found that there is a gap in what is being spent and what is necessary, particularly in India, Brazil and Russia. China has a hefty US$21.5 billion shortfall, but has come a long way by hitting 80% of its target:

Jai Sharda, IEEFA energy-markets consultant and managing partner of Equitorials, cited the introduction of the New Development Bank (NDB), a jointly owned and operated bank funded by the five BRICS nations, as a positive step. However, even though NDB made its first loans this year, IEEFA said this was not enough and that there is a need for private-public partnerships, or what it describes as “blended finance”.

Sharda explained that with a “blended finance” model, public capital can catalyse much larger private investment in renewables, by overcoming various impediments to the flow of private funds. Under this model, every US$1 put forward to fund infrastructure projects in developing countries will draw US$4 in private investment.

Among other benefits, Sharda said: “Public funders can take a greater risk exposure for investments by providing partial or full credit guarantees, political risk insurance, currency swaps etc, which can enhance the risk-adjusted returns for private investors, increasing the attractiveness of the investment for them.”