Mini-grids are growing in number as their economics versus traditional diesel systems improve. David Pratt examines some of the innovations in finance, technology and business models helping the mini-grid sector further expand its reach.

Mini-grids have been a feature of the global electricity system for decades, often serving as a starting point for what would later become larger distribution and even transmission networks. In the modern era their use has been closely tied with remote locations, acting as a key solution in providing energy access to areas not served by national or local grid systems.

Unlock unlimited access for 12 whole months of distinctive global analysis

Photovoltaics International is now included.

- Regular insight and analysis of the industry’s biggest developments

- In-depth interviews with the industry’s leading figures

- Unlimited digital access to the PV Tech Power journal catalogue

- Unlimited digital access to the Photovoltaics International journal catalogue

- Access to more than 1,000 technical papers

- Discounts on Solar Media’s portfolio of events, in-person and virtual

“We’re putting systems into off-grid locations where there isn’t really any cabling because the local network doesn’t go out that far,” said William McQuilter, business director and a co-founder of Zhyhen, a Northern Ireland-based technology firm deploying mini-grid technologies in Africa and Pakistan.

“There’s a saying about connecting ‘the last man in the village’ but we deal with the villages where they haven’t even supplied the first person.”

Delivering universal access to “affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all” by 2030 has become a prominent global target under goal 7 of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Great progress has been made in recent years according to the 2024 State of the Global Mini-Grids Market (SOTM) Report, which found the number of people without electricity fell by 466 million between 2010 and 2021. Mini-grids have been a key driver towards greater energy access, with installations in 2024 set to be over six times higher than in 2018.

The UN has nonetheless predicted that 660 million people around the world will still lack access to electricity by 2030, with Sub-Saharan Africa particularly in need of accelerated efforts. Those in the region without access – around 600 million, according to the World Bank – have increased in recent years, almost returning to 2013’s peak.

Lower costs promoting cleaner mini-grids

An overwhelming technology trend recorded in recent years has been the reduction in the share of diesel capacity in mini-grids, which fell from 42% to 29% in the six years to 2024, and the rise of solar PV mini grids. These systems account for a 59% share of mini-grids, climbing from just 14% in 2018 as advancements in technology have led to increased affordability. The SOTM report points out that the price of PV panels has fallen by around 23% every time the volume of manufacturing has doubled, which has occurred every two years over the past five decades.

Irene Calve Saborit, principal specialist for Energy Access (Partnerships and Innovations) at Sustainable Energy for All and one of the key figures behind the SOTM report, tells PV Tech: “The reduction in prices is not coming from mini-grids especially but from renewables being installed everywhere and the high level of production of PV panels.”

Increased affordability and availability over recent decades is just one of the benefits solar technology offers to mini-grids. Esteban Manuel Pérez González, independent technical consultant for off-grid and energy access projects in Sub-Saharan Africa, explains: “Solar has an advantage compared to other technologies like wind, for example, because of how well the costs scale down due to the minimum building block being a PV module.

“There is also the resource reliability. You know when the sun comes up and down, so the resource is pretty easy to measure compared to wind, where you really need to do some surveys over a year for specific locations.”

The fall in solar PV prices is being reflected across many mini-grid components, particularly battery energy storage. According to BloombergNEF’s 2023 analysis, the average price of lithium-ion battery packs had reached US$139/ kWh at that time compared to an average of US$780/kWh in 2013.

Price reductions for cleantech components, along with advancements in technology and procurement efficiencies, have contributed to an overall fall in capital expenditure (capex). Average capex per mini-grid connection fell from US$1,250 in 2020 to US$707 in 2024, according to the SOTM report, while capex per kWp stood at US$2,200 in 2024 compared to US$3,000 in 2021.

The shifting technology-related economics have contributed to significant growth in solar mini-grids in places like Sub-Saharan Africa, where installations have risen from around 500 in 2010 to more than 3,000 by November 2023, according to the World Bank. Gabriela Elizondo Azuela, manager of the World Bank’s Energy Sector Management Assistance Program (ESMAP), said in 2023 that solar mini-grids “have the potential to transform the power sector in Sub-Saharan Africa”.

Overcoming financial barriers

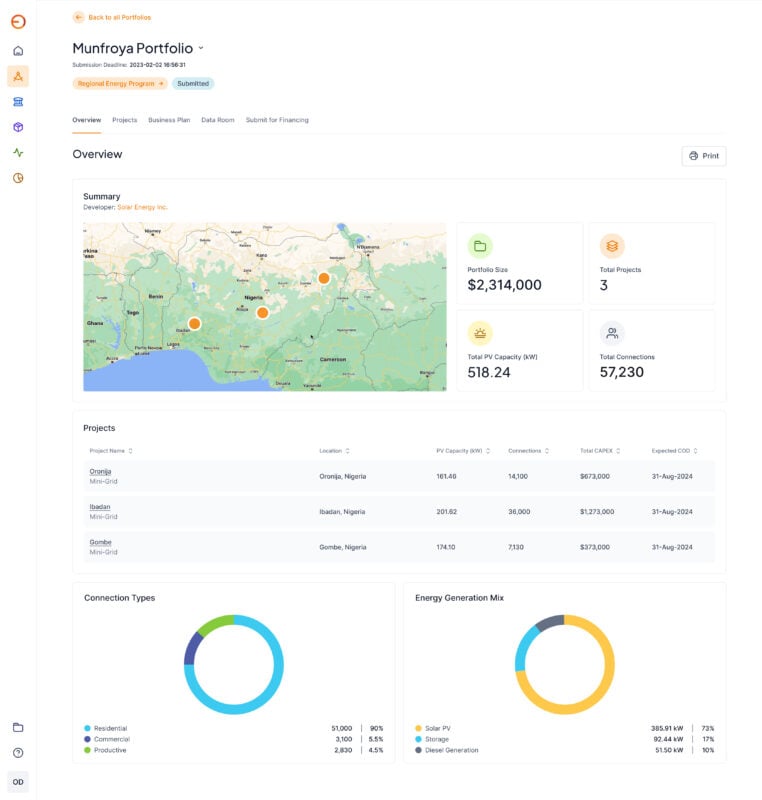

Despite a rise in committed funding, which has reached over US$3.1 billion across 377 programmes with the bulk of investment headed to African initiatives, financing mini-grids can still prove challenging according to Emily McAteer, co-founder and CEO of Odyssey Energy Solutions and previously chief revenue officer of Frontier Power, a SunEdison subsidiary developing solar microgrids in India and Africa.

“There are a couple of things unique to why financing and applying mini-grids is difficult. One is that these are relatively small assets and so standardising the way you evaluate them can really streamline the financing process,” she tells PV Tech.

“The experience [at SunEdison] of living firsthand with the inefficiencies of the financing process for portfolios of many small assets helped us realise that digitisation and standardisation was going to be really essential for financing distributed energy, which led to the birth of Odyssey.”

The company’s end-to-end digital platform, which provides over 2,600 companies with access to more than US$2.6 billion of capital, streamlines the plan-build-operate phases of mini-grid projects beginning with origination, due diligence and financial modelling. A standardised financial model is applied to a range of input data to determine project economics before the same platform can be used to carry out the procurement process for mini-grid developers.

“Essentially because we have so much capital in our platform, which attracts a lot of developers and projects, we end up with a lot of negotiating power with OEMs. Through that sort of aggregation potential, we can offer developers guaranteed lowest pricing and often significant cost savings to procure with those OEMs,” McAteer says.

Displacing traditional mini-grid generation

The combination of digital platforms helping to standardise and validate the value of mini-grid projects and lower component costs is creating ideal opportunities to displace diesel generators.

González explains: “For the last five to ten years you have seen more projects with solar replacing diesel. The sweet spot of the balance of an off-grid system from the financial point of view is with about 90% solar and batteries and 10% diesel. If you have diesel as back up, it’s not that you are using it as the main source and reducing the use of the solar; it’s the other way around. In a solar system with batteries, you use the diesel genset just in case of rainy days or for maintenance purposes. This strikes the right balance.”

According to McAteer, activity on the Odyssey platform would support the view that solar is increasingly being deployed in place of diesel. “We are seeing a tonne of diesel replacements because the unit economics of mini-grids, and generally distributed energy systems, have gotten so strong,” she said.

In countries such as Nigeria, these economics are becoming even more attractive as regulation becomes more supportive towards clean power. The country has long represented a “huge hub” for mini-grids, according to Saborit, largely due to the successes of the Nigeria Electrification Project (NEP). The federal scheme, signed in 2019, is providing energy access to homes, businesses and universities through solar hybrid mini-grids, as well as standalone solar systems for households and small businesses.

The NEP received a combined total of US$550 million from the World Bank and African Development Bank to fund mini-grid tenders and performance-based grants and, according to the SOTM report, had resulted in 110 operational mini-grids as of October 2023.

The removal of Nigerian fuel subsidies in 2023, which had been in place for decades at various levels, has provided a bigger opportunity for solar mini-grids in terms of cost and environmental impact, as McAteer stated: “[Solar] is now the lowest cost form of energy, and you can do some pretty good emissions savings from replacing the diesel on a minigrid.

Digital solutions delivering value

With solar helping to deliver lower capex, operational expenditure (opex) is also benefiting from the advancement in digital technologies, as González explains.

“We tend to focus on capex and initial costs because it’s really sexy from a financial point of view but I would say the opex is as important, if not more. Maintenance is super expensive in rural areas as the systems could be four or five hours from the nearest technical team. That’s when software becomes very important in energy access projects,” he says.

According to the SOTM report, robust software solutions are “revolutionising” mini-grid development across all phases of the project lifecycle. Remote monitoring and control technologies are enabling greater efficiencies in the management of even the most remote sites, yielding estimated cost savings of at least 15% in operations and maintenance (O&M) expenses. O&M software and hardware has “come so far”, according to McAteer, that it can drastically reduce the need for on-site technicians. Lowering reliance on labour in remote locations can deliver significant savings as sourcing local O&M partners often proves expensive, according to McQuilter, who says Zhyphen has previously sent its own engineers abroad as a cheaper alternative.

González continues: “Labour is one of the main drivers of rural energy tariffs, where half the cost per kWh is capex and the other half users are paying is related to maintenance. It is super important to have some way of monitoring the system to understand when and how to act.”

These digital systems also help operators understand the behaviour of those connected to mini-grids, serving a range of purposes related to not just efficient operations but also validating the investment case.

McAteer explains: “Grant providers want to provide grants based on connections achieved with the mini grid since that’s their end goal. That’s a major technology challenge because how do you know that this one rural customer in the middle of nowhere is actually connected and using power?

“Mini-grids have a lot of data coming from them, even more so than other distributed energy assets, so you need to have a really good platform that can collect all that data, pull it in and then analyse it. On top of that, you need to be able to pull in lots of meter data across many customers and analyse the consumption against revenue to figure out how efficient that mini-grid is.

“Despite being very small assets in the scheme of things, mini-grids are among the most complex to both evaluate in the diligence stage and monitor once they’re operating,”

“What you have to keep in mind with off-grid projects is that your counterparty is not the utility, it is not an unlimited load. You have a consumer on the other end, so if [they’re] not at home or can’t pay, you have no consumption and no revenues,” González adds.

“It’s super important to measure the technical and commercial parts of the asset using smart metering to understand customer behaviour so you can adapt your solution and its production to the customer.”

Productive use in Pakistan

Zhyphen is working with Brunel University and the nonprofit Thar Kunwaa Foundation to deliver a mini grid solution under the SolarERA (Solar Electrification of Rural Areas) project for the people of the Thar Desert in Pakistan. Solar generation will power electric sewing and craft machines used by women to produce Thari embroidery and garments.

McQuilter says the project represented the company’s biggest mini-grid project to date, with Zhyphen providing ~250 kWh of energy storage capacity across 55 battery modules to be connected to various properties.

“The desert region means there are challenges that come up that we’ve seen all the time. The inverters don’t work, for example, [due to the heat and the dust]. We’re designing a DC-to-DC step-down system whereby the batteries will be connected to properties [via] a piece of kit being designed by Brunel University and that step down will then power fans, LED lights and sewing machines,” McQuilter says.

Access to reliable clean power from the mini-grid system will enable the Tharis to increase productivity while growing jobs and deliver £22.5 million in revenues by 2031, according to the UK Department for Science, Innovation and Technology, which is funding the project.

Ensuring demand through productive use

Many funders are looking at productive use of electricity (PUE) applications to ensure a level of demand is inherent to mini-grid projects and able to recover the investment costs. The SOTM report states PUE mini grids deliver a lower LCOE than those without energy applications that enhance economic activity, while also delivering societal benefits for local communities. Digital tools can also be used to collect data related to PUE to confirm consumption reaches the threshold that would qualify as a productive use connection, thus ensuring funding is available.

With increased digitisation helping to optimise the size, operations and efficiency of mini-grid systems, and capex expected to continue to fall towards 2030, the levelised cost of electricity (LCOE) is also forecast to continue its decline. A 31% decrease from US$0.55 per kWh in 2018 to US$0.38 per kWh in 2021 has already been recorded, primarily as a result of decreased costs of mini-grid components, particularly PV generation and storage. Country-specific conditions affect this figure across regions, with Husk Power reporting LCOEs of less than US$0.30/kWh at sites in India.

Modelling by the Energy Sector Management Assistance Program (ESMAP) has predicted LCOE for best in-class mini-grids will continue to fall by 2030, driven by anticipated cost decreases in components like solar panels and Li-ion batteries. The prediction ranges from US$0.29/ kWh to US$0.16/kWh depending on load factor, suggesting considerable gains can be made by increasing the efficiency of mini-grid systems.

Despite these positive forecasts, further proliferation of mini-grids will require quicker dispersal of finance – among programmes with available data, only 57% of committed funds were disbursed as of March 2024 – and improvements to the business models supporting them. With the correct regulations and financing strategies in place, mini-grids can continue to build on the successes of their technological development and ensure wider energy access for all by 2030 and beyond.