A German government-funded project has developed a new methodology for predicting the lifetime of inverters used in solar, battery and other energy systems.

The Reliability Design project is intended to provide a more precise methodology for predicting failures and defects in inverters, the causes of which have to date not been well understood.

Unlock unlimited access for 12 whole months of distinctive global analysis

Photovoltaics International is now included.

- Regular insight and analysis of the industry’s biggest developments

- In-depth interviews with the industry’s leading figures

- Unlimited digital access to the PV Tech Power journal catalogue

- Unlimited digital access to the Photovoltaics International journal catalogue

- Access to more than 1,000 technical papers

- Discounts on Solar Media’s portfolio of events, in-person and virtual

The project was led by the Fraunhofer Institute for Microstructure of Materials and Systems (IMWS) in collaboration with Stuttgart University’s Institute for Machine Elements and power control specialists SMA Solar, ELECTRONICON Kondensatoren and MERZ Schaltgeräte.

Inverters are increasingly exposed to harsh operating conditions such as wind, bad weather, dirt and high voltages. Although some inverters achieve a service life of 20-25 years in such conditions, it is still largely unknown which construction methods, materials and designs ensure this. As a result, inverters are manufactured with safety margins and often sold ‘oversized’, which can make them more costly.

In the Reliability Design project, the consortium partners worked together to underpin and expand the existing empirical knowledge with scientifically sound data, models and measurement methods.

They said the result is an efficient and precise methodology for predicting the reliability and service life of PV and battery inverters and their critical components and how they will operate over a typical service life.

“Our results enable a more precise design in the development of new inverters and faster tests during quality inspections. This reduces manufacturing costs because we have a much deeper understanding of the behaviour of the components,” said Sandy Klengel, who led the project at the Fraunhofer IMWS.

Klengel said the consortium analysed field data from inverter failures and examined how other application scenarios can be transferred to these phenomena.

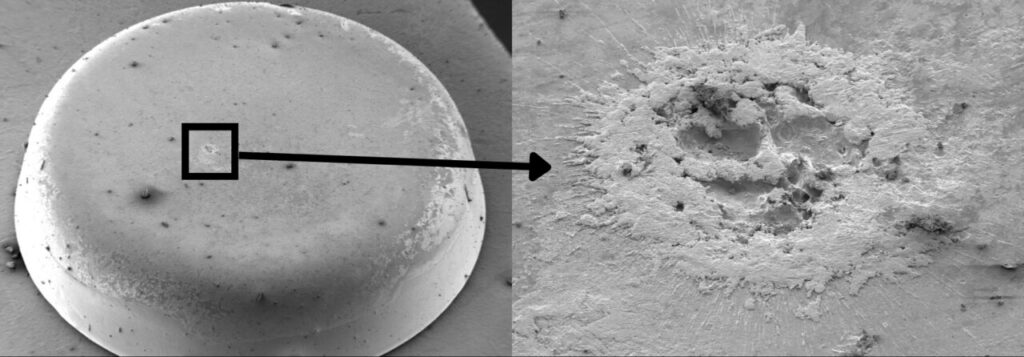

“We can contribute an excellent understanding of material and component behaviour in power electronics and extensive experience in the field of test development, analysis and evaluation of corrosion processes of microelectronic components,” said Klengel. “Thanks to the project, we have now also developed a great deal of expertise in the often particularly critical interaction of voltage, temperature and humidity on insulation materials.”

The project used specially developed test setups to measure defects and degradation mechanisms in various conditions and ascertain which of those were relevant to reliable operation in the field.

Klengel said the new methodology would enable inverter manufacturers to reduce material requirements and thus device costs, without compromising their reliability and service life.

“This is also a contribution to making the renewable energy system more affordable,” added Klengel.