Grid infrastructure has emerged as a key stumbling block in Europe’s transition to a cleaner energy system. Chris Rosslowe of Ember considers how the EU’s power network can be made fit for purpose as an enabler rather than an impediment to greater renewables deployment.

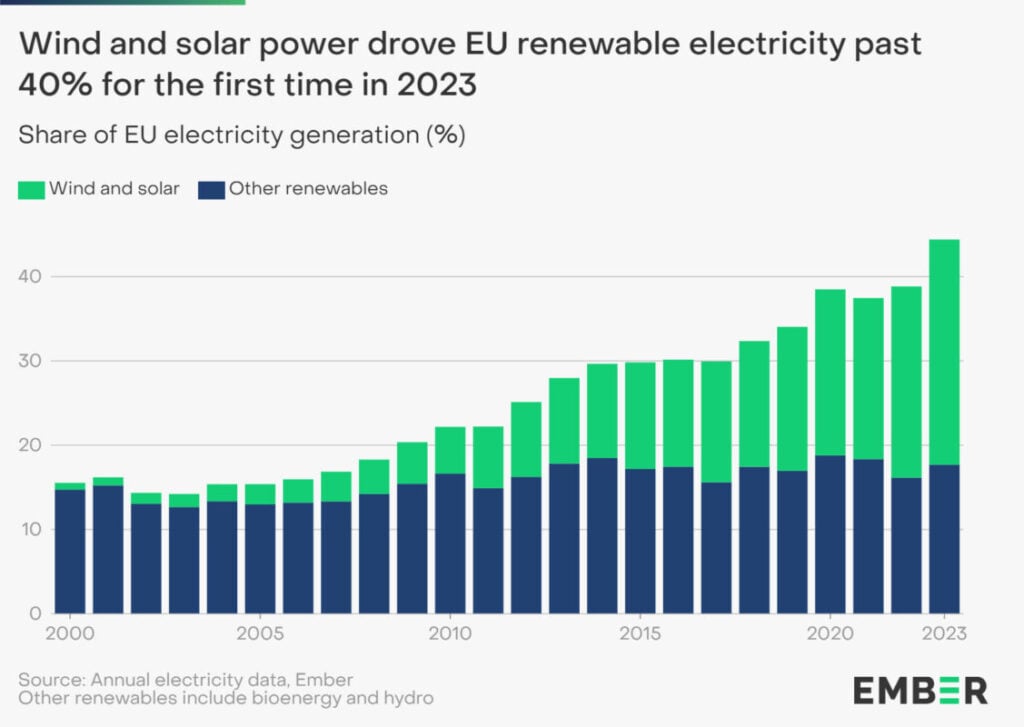

Europe’s power grids are under the spotlight like never before, having emerged as a key bottleneck in the energy transition, which is rapidly gaining pace. Clean technologies are being added to the grid at record rates, with both wind and solar additions breaking records in 2023. This acceleration began with the

EU Green Deal, which significantly raised ambition. Further urgency was injected by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent rush to find alternatives to costly fossil gas. Simultaneous to these events, the economics of renewables and other clean technologies are ever improving. This combination of factors explains why the demands placed on Europe’s grid infrastructure have escalated so dramatically.

Unlock unlimited access for 12 whole months of distinctive global analysis

Photovoltaics International is now included.

- Regular insight and analysis of the industry’s biggest developments

- In-depth interviews with the industry’s leading figures

- Unlimited digital access to the PV Tech Power journal catalogue

- Unlimited digital access to the Photovoltaics International journal catalogue

- Access to more than 1,000 technical papers

- Discounts on Solar Media’s portfolio of events, in-person and virtual

The road ahead doesn’t look easy: the European Commission expects electricity consumption to increase 60% by 2030, by which time the power mix should be roughly 70% renewables, up from 44% in 2023. This cleaner, expanded power system is expected to meet more than 50% of the EU’s total energy demand, even as early as 2024. Put simply, the electricity network will be at the heart of Europe’s future energy system. With the energy transition already in full swing, all of the processes shaping Europe’s power grids need to quickly shift from a mode of incremental changes to a new era of rapid expansion and modernisation that could last decades.

Grid connection delays are already commonly cited as the top barrier to deploying new wind and solar power – the drivers of Europe’s energy transition. Furthermore, curtailment of renewable generation is increasing, wasting cheap power and potentially harming the case for new investments. The present grid challenges have their origins in decades of under-investment in ageing grid infrastructure, linked to persistent underestimation of renewable energy growth, which is now coming home to roost. What we’re left with is a grid that is unprepared to deliver power from the best renewable locations to our economic centres.

The IEA used its first major analysis of power grids last year to send a warning to Europe: failure to develop grids quickly will not only result in higher carbon emissions but also continued dependence on fossil gas. In that sense, grids represent a critical piece in Europe’s security puzzle. It has also repeatedly been shown that by enabling a more integrated European electricity market, grids create efficiencies that ultimately save consumers money.

Arguably the most important roles in this critical project belong to Europe’s Transmission and Distribution System Operators (TSOs and DSOs for short). They are the technical enablers of the energy transition, responsible for planning and executing the necessary grid enhancements. But there are important roles for others, too, from regulators to policymakers; all parties need to pull together to tackle the problems urgently.

In the rest of this piece, I will discuss five key challenges for Europe’s grids, before discussing some of the solutions that have been proposed, including by Ember’s own research. Those challenge areas are: grid connections, planning and oversight, permitting, transparency and collaboration, and investments.

The challenge

Grid connections

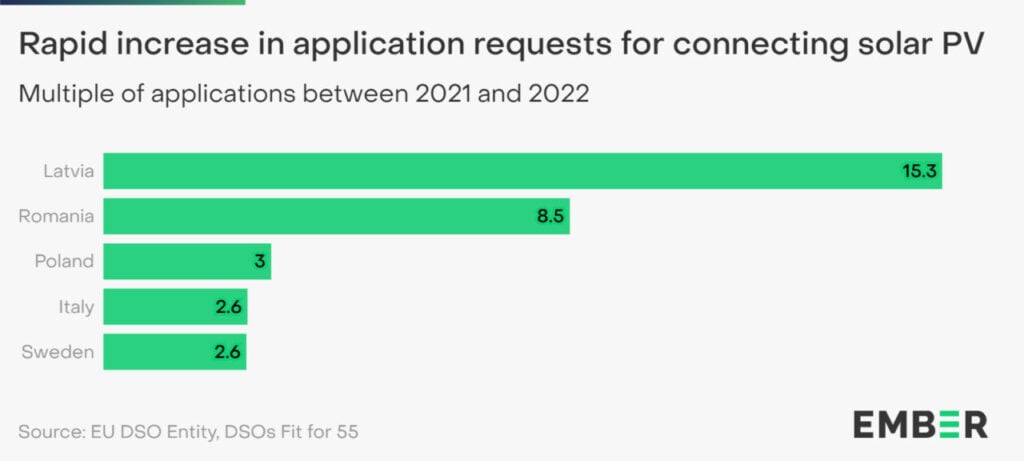

The simple fact is that many more assets are trying to connect to the grid in a much shorter time than ever before. The situation has exposed our current processes – which may have worked in yesterday’s world of fewer, larger, less frequent connection requests – as cumbersome and inefficient. While data on grid connection queues is scarce, the few available numbers are eye-watering. According to Wind Europe, at least 100GW of renewables projects are waiting for grid connection in Spain, with more than 50GW in Romania and 40GW in Bulgaria. While it should be noted that many of these projects will be somewhat speculative, the numbers far exceed the operational capacities in these countries.

SolarPower Europe reports that the average lead time to connect ground-mounted PV projects can go up to eight years, with an average of around four years. Even small PV can take up to a year to connect. Grid connection times are even longer for wind projects, such that WindEurope now cites these delays as the top barrier to accelerating roll-out. Just this year, the Netherlands announced a one-year delay in reaching its target of 21GW offshore wind due to grid connection delays.

Grid connection rules are complicated, often unclear and highly non-uniform across member states. Compounding this is a lack of administrative capacity to help developers navigate the bureaucratic labyrinth. Paper documentation is still central to parts of the process in many member states, which is scarcely believable in the 21st century.

Planning and oversight

Moving on to my second challenge, a historic failure of planning is one of the reasons for the connection bottleneck and shortage of grid capacity. At the risk of sounding trite, the best time to plan for a highly renewable and electrified energy system was ten years ago, but the second best time is today. Transmission system planning at the national level is typically conducted on a two-year cycle with a ten-year outlook. In theory these plans feed into the Europe-level ten-year planning process orchestrated by the network of system operators (ENTSO-E), which evaluates interconnection needs.

However, Ember’s research highlights a fundamental problem: national grid plans frequently lag behind the latest national energy targets, which in turn lag behind EU energy targets (due to delayed transposition), which in turn lag behind the reality of the accelerating energy transition. The result of this cascading delay is that grid plans are always playing catch-up to the latest ambition and the real economy. This is exactly the opposite of what should be happening – networks should enable, not limit, the expansion of clean energy.

One of the key buzzwords around grids at the moment is ‘anticipatory’ investments. This is the idea that grid capacity can be built in anticipation of its being needed. Bringing this concept to reality was a key theme of the EU Action Plan for Grids (EU APG), and it is desperately needed. Anticipatory planning is imperative for anticipatory investments, as you cannot proactively build infrastructures without bold and forward-looking planning.

It would be unfair to lay too much of the blame for this with TSOs or DSOs. In many ways they are limited in what they can plan for by the regulatory framework. Furthermore, oversight of development plans by national regulators remains largely limited to financial implications, ignoring the question of whether the planned infrastructure is sufficient to deliver on energy and climate goals.

Permitting

My third challenge area is grid permitting. We have heard a lot about the permitting of new generation projects, but slow permitting of grid projects is also an important blockage. As well as the time taken to permit new grid capacity, there are also efficiencies to be gained in the sequencing. For a new project, it is currently common for the generation part and the grid part (if necessary) to go through permitting one after the other. The EU DSO Entity has, sensibly, called for these to be conducted in parallel where possible.

This would, however, require better cooperation and communication between project sponsors and local grid operators, which brings me to the next challenge.

Transparency and communication

Communication between all actors involved in building grids and connecting renewables is insufficient. Grid users lack information on where they are likely to obtain a timely grid connection, helping them to plan projects in greater harmony with the existing grid. Many DSOs produce so-called ‘hosting capacity maps’ with this information, but there is a great variation in content and quality across Europe’s 2500 DSOs. Simultaneously, DSOs are often not informed as early as they could be about new assets wanting to connect to the grid. Greater openness and willingness to collaborate is needed both ways.

The issue of poor communication is not helped by a lack of data transparency around grids. Official permitting and connection data are not made available by public administrations. TSOs and DSOs do not collaborate closely enough on data exchange, nor is data exchange sufficient between them and grid users. The resulting lack of data exacerbates several problems. Firstly, the debate as a whole is starved of clear information, limiting any discussion about solutions. Secondly, tracking and reporting on key problems such as grid congestion and connection queues are impossible, limiting the ability to monitor improvements. Thirdly, long-term visibility of network needs is not as well informed as it could be, hindering planning and supply chain preparation.

Investment

The fifth and final challenge area in my (non-exhaustive) list is investments. The European Commission estimates that €584 billion (US$627.6 billion) investment is needed between 2020 and 2030 at all grid levels. The need is greatest at the distribution level, where Eurelectric estimates around €400 billion is required by 2030. Unlocking these investments will be no small feat. There are three main drivers behind the estimated needs. Firstly, renewables-related expansions and replacements. Secondly, modernisation (more than 50% of the grid has been in operation for over 20 years). Thirdly, the increase in electrification rates necessary to decarbonise other sectors means physically strengthening the grid is a necessity.

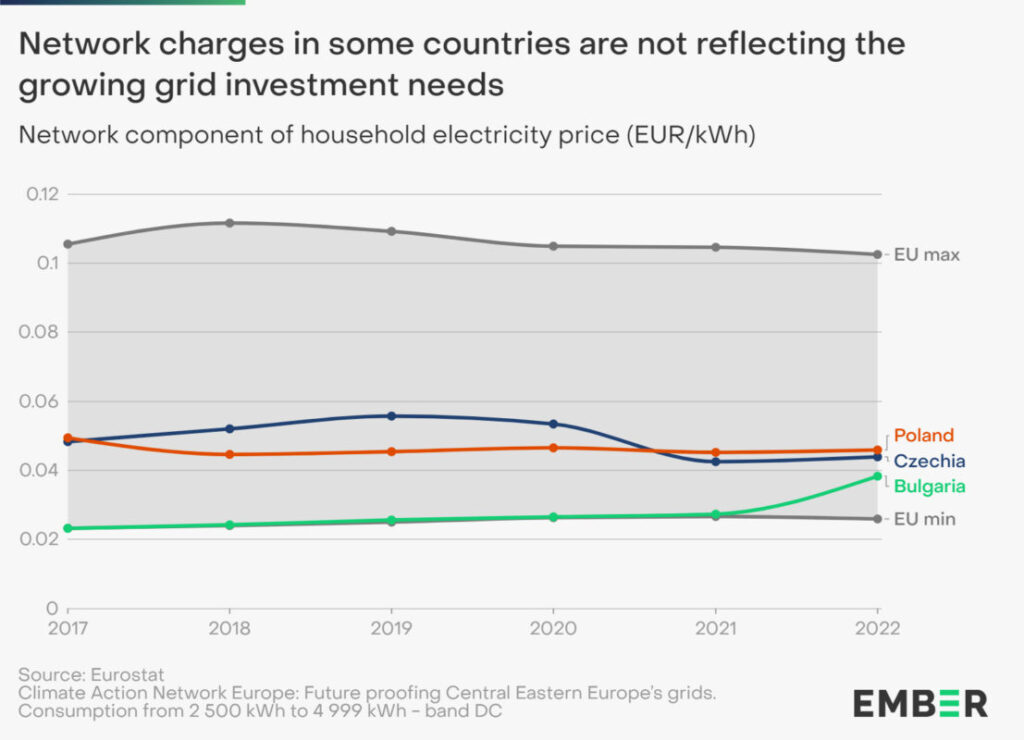

The good news is that system operators are large infrastructure players who know how to handle capital intensive projects. The problem is the framework in which they operate doesn’t yet incentivise the right volume or types of investment, and access to finance is becoming a problem. Investments have been slow to pick up, especially in Central and Eastern Europe, where the available EU funds (for example, the Modernisation Fund) have also been under-used for electricity grids. Under the current model, grid operators recoup their costs through tariffs, but a reluctance by regulators to allow higher tariffs has limited investment. The share of tariffs allocated to grid costs has even decreased in some countries.

As well as sluggish capital investment, there are insufficient incentives for the uptake technologies that would improve the operation of the grid, such as smart grids, network efficiency and innovative technology. This is because system operators are typically remunerated based on their capital expenditure, with little consideration for their operational expenditures, which these grid improvements would help to minimise.

The solutions

The solutions to the above challenges are being debated at the highest political levels. The problem and its solutions are so cross-cutting, from finance to planning to skills, that it is vital to sustain this political attention. Improvements need to be made across all processes and rules that dictate not only what gets built, but also why, when, and how.

Grid connections

Governments and system operators must clarify and streamline grid connection rules. The way connection requests are assessed also needs to change, broadly moving from the widespread “first come, first served” system to “first ready, first served”. Projects could also be clustered for the purposes of assessment. Furthermore, connection management processes need to be optimised, primarily through digitalisation. These would be major steps towards reducing grid queues and achieving faster, more efficient integration of assets. Alongside these changes to rules and processes, efforts should be made to standardise them between regions and member states, reducing complexity for renewables developers and investors.

All this should be done without forgetting the rights of energy communities, who play a key role in the energy transition, but often lack the resources to compete for grid capacity. Good practice would be to prioritise community energy projects or reserve grid capacity for their use. The EU APG proposes another important solution, instructing national regulators to provide a clear framework to discourage connection applications by unsubstantiated projects, which can block useful grid capacity for years.

Planning and oversight

When it comes to grid planning, longer-term perspectives are needed. Plans need to consider Europe’s 2030 (REPowerEU) and 2040 targets (when agreed), and the shared 2050 climate neutrality goal. Some TSOs already look beyond the mandatory ten-year horizon. The Dutch TSO publishes a ‘target grid’ for 2045. German TSOs publish outlooks to 2037 and 2045 (Germany’s net-zero date). While it’s true that longer outlooks are less certain, only by taking such perspectives can TSOs understand the need for anticipatory investments and achieve timely execution of large projects that can take a decade or more.

Planning at the distribution level is subject to even less scrutiny than the transmission level. To address this, the EU DSO Entity is instructed by the AGP to support DSO grid planning by mapping the ‘existence and characteristics of distribution development plans’. National regulators are also encouraged to provide guidance to DSOs on planning and promote consistency among plans. This is a good start, but we need much stronger assurances and guarantees that these sub-national plans will be fit for purpose. The end goal should be high-quality plans that are aligned and consistent across voltage levels as well as regions and member states, and which are fully compatible with Europe’s climate and energy targets.

We also need more forward-looking regulation, allowing more risk when it comes to grid planning and investments, but without totally transferring this risk to end consumers. We must not forget that limiting development to current system needs may increase future system costs more than over-investing. At the level of cross-border interconnection, oversight is provided by ENTSO-E and ACER, who do consider energy and climate goals in the planning process. How can we embed the same considerations into the way national and sub-national systems are planned? The introduction of a net-zero mandate for national regulators is one way of achieving this.

Permitting

The revised Renewable Energy Directive aims to accelerate permitting of both generation and grid. Member states can optionally designate ‘dedicated infrastructure areas’ – similar to the much-discussed ‘renewables acceleration areas’ – where grids and storage infrastructures can benefit from more streamlined environmental assessments. This could accelerate grid build-out significantly, but timely implementation at the national level will be key.

The APG commits the Commission to providing specific guidance on dedicated infrastructure areas by mid-2025. In the meantime, member states should look to do whatever they can to accelerate the authorisation and permit granting processes, without undue harm to the environment or exclusion of the citizens.

Transparency and communication

A quick win for data transparency would be the publication of regular data on congestion, curtailment and available grid capacity. This would lead to improved understanding of grid conditions for all potential grid users, steering development towards available capacity and focusing solutions on problematic areas. In turn, potential grid users should provide data on their projects to DSOs at an early stage, helping them plan and understand future grid needs.

Better cooperation between TSOs and DSOs is required for active system management as the traditional ‘one-way’ power system becomes a more distributed ‘two-way’ system. This should help both to realise the coordinated use of distributed flexibility, which in turn could reduce the need for new grid investments. Regional collaboration is also important, especially among Central and Eastern European Member States where interconnection is relatively low. Shared capital investment for interconnection capacity across multiple governments, and more coordinated planning, could help this region reach EU interconnection targets.

Investment

Finally on investments, one of the most significant things provided by the EU APG is the promise of guidelines on anticipatory investments. This cannot come soon enough. The plan also promises new financial instruments for grid investment. However, it’s not just about making money available. More needs to be done to promote the use and facilitate access to these funds, especially for the distribution grid.

Beyond tinkering with the current system, we need a deeper re-think of the value provided by electricity grids and who pays for them, especially as we enter a more electrified world with the power system at the heart of Europe’s energy system. Such a re-think presents opportunities to connect the way we develop grids to how we address more structural problems such as energy poverty, and how to incentivise electrification in a just way. Future energy bills will be increasingly linked to interest rates due to the capital-intensive nature of the energy transition, including investments in grids. In this context, and considering the wider societal benefits that clean energy brings, we should be questioning whether electricity bills are the best way to pay for grid upgrades going forward.

Conclusion

There’s no doubt that significant progress has been made in the last 12 months in our collective understanding of Europe’s grid problem and solutions. The case for continued focus is strong. According to Eurelectric, around 90% of future grid investments could be captured by EU companies, delivering economic benefits to all regions of Europe. The speed of change is also possible, given the political will. The project to decouple the Baltic states from Russia’s power system is inspirational. Already an ambitious project, involving construction or reconstruction of over 1,200 km of high-voltage lines, the deadline was brought forward following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This shows that complex grid projects can move rapidly with enough political will and support in place.

This is the spirit that policymakers, regulators, grid operators and administrators alike need to adopt. The shape of our future energy system will be defined by the grid – we need to ensure it can support the sustainable, electrified, resilient, and people-centred energy system that Europe needs.

Chris Rosslowe is a senior energy and climate data analyst at Ember. He uses future energy scenarios to provide insight and guide policy-making for the energy transition. Chris’ recent work focuses on the barriers and enablers of wind and solar power, as the key technologies that will deliver a clean energy system for Europe.