India’s push to achieve its ambitious 500GW renewable energy target by 2030 requires a significant growth in investment, but if commissioning delays and a new focus on dispatchable projects cause costs of capital to increase then the country could fall 100GW short, according to a new report by think tank Ember Climate.

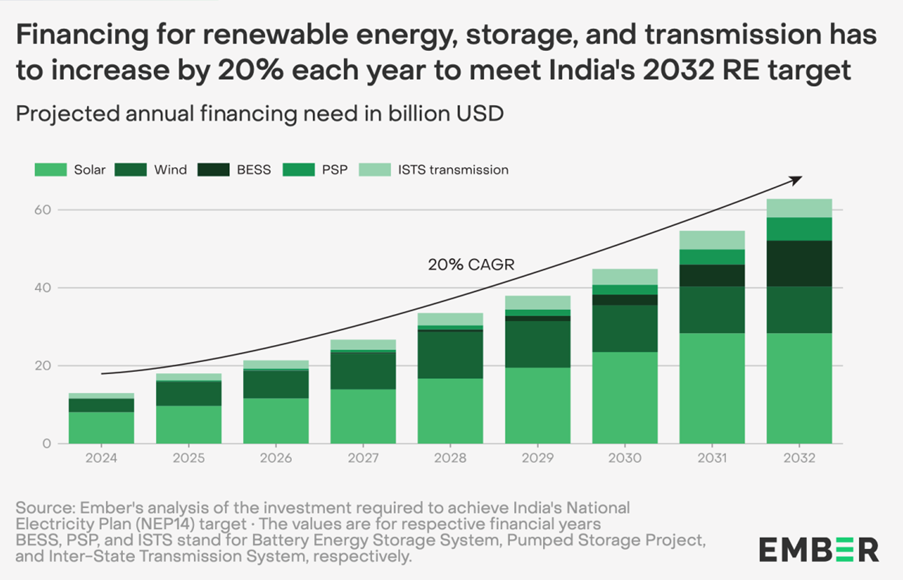

In FY2024, a total of US$13.3 billion was invested in renewables, storage and transmission in India. However, to meet the National Electricity Plan (NEP-14) by 2032, the annual investment requirement will be US$68 billion, which needs a growth rate of 20% each year, Duttatreya Das, energy analyst, Asia, at Ember Climate tells PV Tech Premium.

Unlock unlimited access for 12 whole months of distinctive global analysis

Photovoltaics International is now included.

- Regular insight and analysis of the industry’s biggest developments

- In-depth interviews with the industry’s leading figures

- Unlimited digital access to the PV Tech Power journal catalogue

- Unlimited digital access to the Photovoltaics International journal catalogue

- Access to more than 1,000 technical papers

- Discounts on Solar Media’s portfolio of events, in-person and virtual

Das, an author of the report ‘Navigating risks to unlock India’s 500GW renewable energy target by 2030’, adds that the main roadblocks to the necessary financing increases are risks around project delays and the evolving nature of new energy tenders, which combined could raise the cost of capital by 400 basis points. This is critical because the cost of financing is almost half of the cost of renewable power in India.

One of the most pressing issues is the prevalence of commissioning delays, caused by land acquisition bottlenecks, grid connectivity issues and power purchase agreement (PPA) slowdowns. These setbacks, which have historically averaged a delay of 17 months and sometimes extend beyond two years, increase financial uncertainty for developers and investors.

The cost of clean power

Meanwhile, another major shift in India’s renewable energy landscape is the rise of Firm and Dispatchable Renewable Energy (FDRE) projects, which require generators to meet specific demand profiles rather than simply supplying power as it is produced.

Until recently, the government opted for “plain vanilla” PV systems that supply energy as and when they generate it, but last year more than 60% of all tenders were for FDRE projects, with the eventual aim of having 24/7 renewable electricity, says Neshwin Rodrigues, Ember Climate’s senior energy analyst.

Indeed, the Indian Central Electricity Authority recently advised state utilities and all renewable energy implementing agencies to co-locate energy storage systems (ESS) with solar PV in future tenders.

“India is now getting into setting up more and more dispatchable renewable energy through FDRE, and there are multiple risks that come along with these new types of renewable energy tenders or capacities that an investor would have to deal with,” says Rodrigues.

Developers must account for penalties if they fail to meet these demand profiles, leading to oversized project designs that generate excess electricity. This surplus often ends up in the wholesale market, where price volatility and potential price cannibalisation create additional financial risk.

Rodrigues suggests one way of mitigating price volatility would be to adopt a UK-style Contracts for Difference (CfD) system where a fixed ’strike price’ is guaranteed for electricity. When market prices fall below the strike price, the generator is compensated for the difference, and when market prices exceed the strike price, the generator pays back the surplus.

Investing in more energy storage capacity is another option. However, uncertainty over battery technology and costs are also causing concern. Given that FDRE projects require substantial storage facilities, fluctuations in battery costs could also significantly impact financing.

Das notes: “Any new endeavour would entail new risks, and that’s inherent to the design of these mega infrastructure projects with big solar, wind and a large amount of storage all combined together.”

Referring to both project delays and the new FDRE landscape, Rodrigues also warns: “We estimate that if these risks actually materialise into a higher cost of capital, India might build up 100GW less of renewables capacity till 2030 and miss its 500GW target.”

Domestic content effects

Beyond project execution risks, India’s focus on domestic solar module manufacturing could also hamper project timelines. Higher levels of Domestic Contact Requirement (DCR) tenders have rubbed up against limited local manufacturing capacities, leading to revisions in tender specifications and subsequent delays.

Inadequate local supply chains, transportation challenges for heavy equipment and lengthy permission processes further contribute to extension of project timelines and therefore risk pushing the cost of capital up further.

One of the key concerns with localisation is the rise in domestic module and cell costs, states the Ember Climate report. With the implementation of the Approved List of Modules and Manufacturers (ALMM), module prices are reported to have increased by 20%. Meanwhile, the cost of cell manufacturing in India is presently estimated to be 50% more than imported Chinese cells.

Outside of pure Indian manufacturing, even the performance of newer TOPCon module technology is under the spotlight after multiple testing agencies and universities have reported significant UV-induced degradation (UVID) occurring in short periods of time. The report warns that “careful technology appraisal” is necessary to avoid such pitfalls and greater quality assurance from government is needed to enhance investor confidence.

Although financial difficulties have historically plagued India’s distribution companies (Discoms), current regulatory measures have stabilised payment timelines for renewable developers and Discoms not paying on time has no longer been a major risk in the last four years.

While Discom finances are still questionable, says Rodrigues, noting that their losses “worsened” last year, he adds that government mechanisms, including clearer processes for payment delays and options for developers to sell excess power in the wholesale market, have mitigated immediate concerns.

“With the deepening of the wholesale market, that risk itself is going to reduce,” Rodrigues says. “But again, that’s a ticking time bomb.”

With investment needs growing each year, addressing the various risks drawn out by the report will be crucial to ensuring India meets its renewable energy ambitions.

Rodrigues says: “Understanding project-specific financing risks for renewable energy projects is key to designing targeted mitigation measures that keep the cost of capital low. Staying attuned to evolving risk profiles in renewables is essential for sustaining their growth and ensuring India meets its renewable energy targets.”