It is almost a decade since the United Nations (UN) agreed to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that now drive much of the world’s investment activity in developing countries. Progress has been mixed across the 17 goals, which includes ensuring “access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all” under SDG 7.

According to the latest official SDG 7 progress report, the current pace is “not adequate to achieve any of the 2030 targets”, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) where average annual increases in electricity access have barely exceeded population growth in recent years. Over 83% of the world’s unelectrified population live in the region as a result, with 600 million lacking access to electricity.

Unlock unlimited access for 12 whole months of distinctive global analysis

Photovoltaics International is now included.

- Regular insight and analysis of the industry’s biggest developments

- In-depth interviews with the industry’s leading figures

- Unlimited digital access to the PV Tech Power journal catalogue

- Unlimited digital access to the Photovoltaics International journal catalogue

- Access to more than 1,000 technical papers

- Discounts on Solar Media’s portfolio of events, in-person and virtual

A report presented to the African School of Regulation (ASR) in September, and seen by PV Tech Premium, outlined the difficulties in getting back on track over the next five years. Less than one-fifth of African countries have targets to reach universal electricity access by 2030 while fewer than half have set targets that are less ambitious than the goals under SDG 7. This is likely to leave a projected 540 million people in SSA still waiting for access to power by 2030.

Off-grid solar and mini-grids offer one of the most cost-effective means of delivering electricity access and, as detailed in PV Tech Power issue 41, cost reductions in solar and battery energy storage systems alongside advances in management systems have removed many of technology-related barriers to deployment. Mini-grids are expected to play a crucial role in achieving complete electrification in SSA alongside improved grid connectivity and proliferation of stand-alone systems.

Business model limitations

About 3,000 mini-grids are currently operating in SSA, primarily funded through grants and non-commercial capital, with many supported by business models of questionable sustainability. Unlike the development of distribution and transmission grids, which have been heavily subsidised to help cover initial capital expenditure (capex) costs, mini-grids are characterised by part-subsidisation of capex, private ownership and tariffs of various levels.

According to Irene Calve Saborit, principal specialist for energy access (partnerships and innovations) at Sustainable Energy for All, this is not the right approach if the goal is to attract private capital.

“The least cost solution is going to be mini-grids for a lot of sites but no way on earth with the existing business model [of a] cost reflective tariff with partial capex subsidisation is anyone going to invest. Most of the villages that [could be] electrified through a mini-grid for minimising cost will not be bankable,” she tells PV Tech Premium.

This often remains the case even with projects tied to productive use of electricity (PUE), which aim to sustain mini-grid profitability by connecting to local economic activities to ensure a level of demand is maintained to help recover investment costs. While PUE is becoming a more common requirement for mini-grid funding, it fails to fully address the high tariffs paid by those connected to mini-grids compared to main grid networks.

Saborit says: “A cost reflective tariff implicates a higher tariff than the rest of the world [so] when people talk about PUE as industrialisation and not diesel displacement, it’s mathematically wrong because the electricity price is going to be [higher than] in the rest of the world. So you will never produce anything industrially because it’s always going to be cheaper to import and that’s something we need to think about if we are going to be serious about SDG 7.”

Overcoming the challenges posed by existing mini-grid business models has never been more important, following the unveiling of Mission 300 by the World Bank and the African Development Bank Group. The two financial institutions partnered in April to provide at least 300 million people in Africa with electricity access by 2030 through grid connections or distributed renewable energy solutions, such as solar mini-grids and stand-alone solar installations.

This ambition has yet to be matched by the guidance needed to achieve Mission 300’s goals, despite the acknowledgement that drawing in private capital will be essential in filling funding gaps.

Delivering sustainability and scalability

The key to creating mini-grids fit for SDG 7 lies in making them commercially sustainable and scalable. A non-sustainable model does not meet the UN goal’s requirements, since electricity access may disappear after a few years, while a model that cannot attract the investment needed to scale and maintain mini-grids will also fail to deliver universal access for all.

For the mini-grid industry to be sustainable, developers need to receive a revenue that covers the total cost of providing the service, meaning capex and operational costs (opex), on a permanent basis. According to Saborit, this will lower the perceived risk of cost recovery for private investors and deliver a lower weighted average cost of capital (WACC).

“If you ensure to them a regulated return with enough collateral, warranties and whatever else is needed to be perceived as a safe return, then the WACC will decrease a lot [meaning] the whole electrification plan would change dramatically,” she says.

This will require a change in mindset of all stakeholders involved. Investors need to provide long-term commitments and take on a role similar to a utility; customers must accept that electricity is a service that must be paid periodically on a regular basis; and the government and regulator need to take responsibility for the financial viability of the indefinite supply of electricity to bridge the gap between the cost of service of each non-viable mini-grid and what customers can afford.

This would support a combined business model, regulation and financial strategy able to encourage efficient delivery and reasonable levels of performance in reliability, quality of service, revenue and the incorporation of PUE.

The Integrated Framework for Electrification

The framework being advocated by Saborit focuses on equalising the tariffs paid by those connected to mini-grids with customers connected to main grid systems. Expanding cost-of-service regulation, established on solid concession contracts, to cover both on-grid and off-grid solutions would ensure revenue requirements align with efficient costs of operations and capital investments.

Saborit says: “The model we are proposing basically will increase a little bit the tariff for everyone in the country and we use that excess to finance the PV panels and minigrids. You charge the same tariff as the rest of the country but, using that different tool, subsidise the cost of the mini-grid.”

Unlike incentive regulations, which are only reviewed periodically, cost-of-service models require annual reviews to reflect real-time costs and execution of electrification plans. This creates a more responsive and predictable financial model that offers a more stable investment proposition.

The Integrated Framework for Electrification (IFE) approach recommended to the ASR calls for regulation, business models and financing of mini-grids to be integrated into bespoke strategies developed for each country, which vary in market dynamics and needs.

“Nigeria is Nigeria, DRC [Democratic Republic of Congo] is DRC. There are not similar markets elsewhere in the rest of the continent. In Nigeria you have high consumption and high ability to pay compared to the rest and in the DRC there is also high consumption. That is not going to happen in Zambia or Benin or Niger, they are not the same,” Saborit explains.

The IFE strategy stands on four guiding principles that can be applied across all locations:

- Cost effectiveness achieved through national electrification strategies based on the integration of grid extensions, mini-grids and standalone systems to ensure a least-cost outcome compatible with available funding and national priorities.

- Sustainability of each electrification mode based on permanent cost-of-service remuneration, utilising regulated tariffs and a subsidy, established on solid concessions contracts to ensure electricity supplier costs are covered and an appropriate return on investment is achieved.

- Scalability through utility-like entities responsible for providing permanent supply across a defined territory for a specified long-term period, including default and last resort providers to maintain service.

- Focus on development alongside other sectors to unlock potential of providing electricity access to improve human welfare and promote economic development.

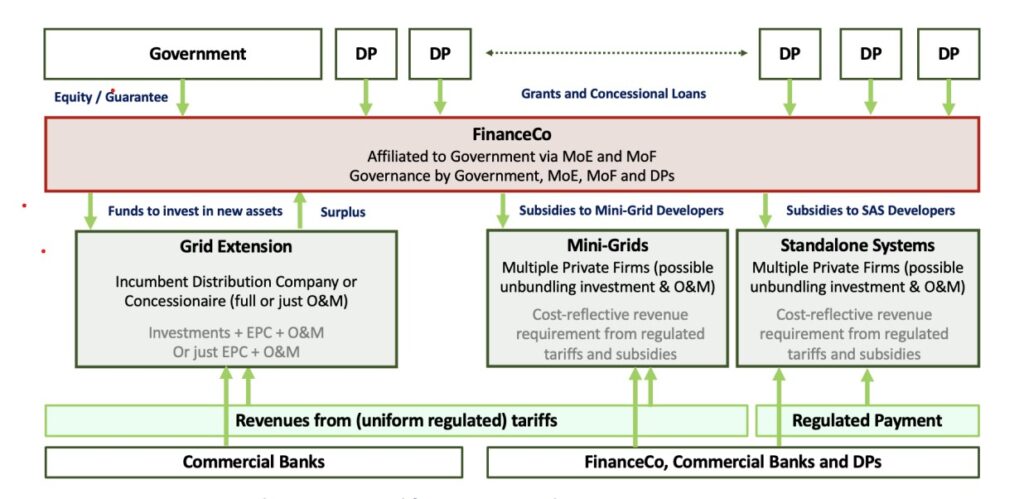

These activities would be backed by a series of entities designed to take responsibility for each element of the deployment programme. A public FinanceCo entity would ensure political commitment and act as a hub for all the financing sources related to the mini-grid project or portfolio by managing flows of public and private funds to various AssetCos. These would develop and build the projects before OpCos take over management of ongoing operations.

Unbundling the off-grid activities divides the risk associated with projects which, alongside long-term public backing, makes them more attractive.

It is hoped this integrated approach offers enough flexibility to be designed for individual countries at scale while adhering to the fundamental principles of SDG 7. Its sustainability and scalability are ensured by an effective financing strategy, supported by a stable regulatory environment, that brings together government, private investors and development partners to manage subsidies, adjust tariffs and mobilise capital.

Together under this approach, it is hoped that enough investment can be raised to deliver the 160,000 mini-grids needed to provide electricity to 380 million people in SSA by 2030.

David Pratt is a freelance journalist.