JP Casey reports on recent developments in Western Europe, where past and future elections are creating waves.

Germany

Western Europe is home to a number of leaders in the continent’s solar sector. According to trade body SolarPower Europe’s latest EU Market Outlook report, covering the period 2023 to 2027, Western Europe is home to five of Europe’s 14 gigawatt-scale markets – Germany, the Netherlands, France, Austria and Belgium – and none is larger than Germany, with a total installed capacity of 81.7GW at the end of 2023.

Unlock unlimited access for 12 whole months of distinctive global analysis

Photovoltaics International is now included.

- Regular insight and analysis of the industry’s biggest developments

- In-depth interviews with the industry’s leading figures

- Unlimited digital access to the PV Tech Power journal catalogue

- Unlimited digital access to the Photovoltaics International journal catalogue

- Access to more than 1,000 technical papers

- Discounts on Solar Media’s portfolio of events, in-person and virtual

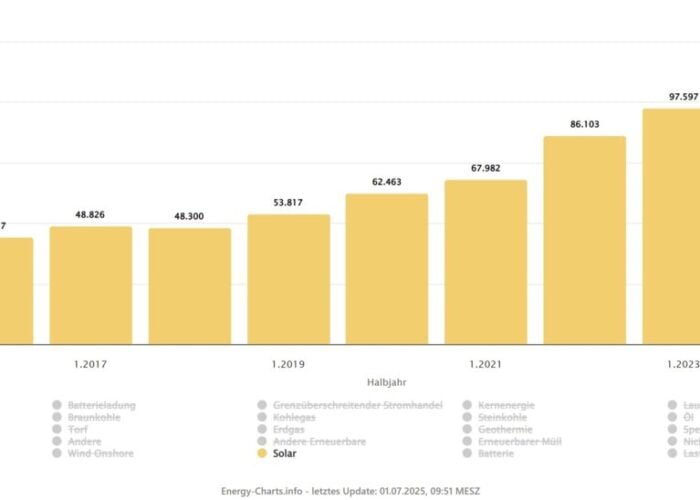

“Solar energy has been the most popular form of energy in Germany for many years,” Carsten Körnig, managing director at the Bundesverband Solarwirtschaft (BSW-Solar), Germany’s national solar association, tells PV Tech Power. “At 15GW, the newly installed solar power capacity in 2023 has almost doubled compared to the previous year.”

Körnig notes that, from 2026, the government is aiming to install 22GW of new capacity per year, which would push Germany’s total installed solar capacity to 215GW by 2030, and 400GW by 2040. Crucially, these targets align with those submitted to the EU by the government as part of Germany’s updated National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP), with the German target of 215GW of solar by far the most in all of Europe, more than double Italy’s target of installing 80GW of solar PV, the second-most ambitious goal.

Strong government support for solar has been a hallmark of the German solar expansion, and was buoyed further by the passage of the Solarpaket I tranche of legislation in April this year. This framework makes a number of changes to German solar legislation, including the raising of feed-in tariffs for commercial and industrial (C&I) solar projects by €0.015 (US$0.016) per kWh, a move intended to make distributed solar more commercially viable and thus more attractive to potential investors.

“This will make it easier for property owners, tenants, farmers and other professional investors to access inexpensive solar power,” says Körnig of the new legislation. “According to the draft law, barriers to accessing solar power generated close to the public, to the electricity grid and to suitable locations for larger solar power plants are to be removed.”

However, as is always the case with a market that has benefitted from government support, impending elections in Germany cast doubts over the long-term future of the solar sector. Germany is slated to have federal elections in 2025 and radical changes to the political status quo could derail this progress.

Yet Körnig is optimistic that Germany’s strong solar sector will endure any such changes, most notably because the sector is, for the most part, an attractive investment destination.

The SolarPower Europe report notes that, in March 2023, Germany’s auction for ground-mount solar power was oversubscribed by 186%, while tenders for rooftop solar launched in June and October were oversubscribed by 75%, showing very strong interest in funding new German solar projects.

“Of course, legal regulations also help to increase the attractiveness of solar energy, as do tax breaks, such as the VAT exemption on the purchase of PV systems and electricity storage systems that has been in force since the beginning of 2023,” says Körnig.

The Netherlands

The Dutch solar sector has also benefitted from a growing distributed sector. The rooftop solar sector alone added 1.8GW of new capacity in 2022, accounting for 46% of new capacity additions that year, helping the total installed capacity of the Dutch solar sector exceed that of France by the end of 2023.

SolarPower Europe expects this growth to remain steady in the coming years, forecasting growth of 1.6GW in the rooftop sector in 2023 and 1.8GW in 2024. As is the case in Germany, this sector has also benefitted from supportive legislation, such as the Investment Subsidy for Sustainable Energy and Energy Savings (ISDE), which saw its funding increase to €600 million this year to subsidise the cost of devices such as heat pumps and solar panels.

Crucially, SolarPower Europe reports that, in 2023, the sector achieved “average negative subsidy levels”, meaning that the government is no longer making a loss on financially supporting new solar installations, a state of affairs that could encourage more government support for solar. Similarly, the senate rejected a proposed bill to phase out the net metering scheme in February 2024, a move that Juan Monge, principal analyst for distributed solar in Europe at analyst Wood Mackenzie praised.

“The debate on whether to phase out net metering in the Netherlands has been going on for years, with previous attempts at killing the programme,” explains Monge. “This decision brings clarity to the market, providing prosumers with some certainty on expected system economics. Maintaining net metering will also prevent double-digit market contraction for standalone residential solar in the near term.”

The Netherlands is also a strong investor in floating solar, with a funding programme announced in April 2023 setting aside €44.5 million to add 3GW of offshore solar capacity to the country’s energy mix. The government aimed to pair these floating solar projects with offshore wind farms, building floating panels between turbines to take advantage of existing energy infrastructure in place off the coast.

“This tech will be deployed by hybridising offshore wind farms in the North Sea,” says Daniel Garasa, a Wood Mackenzie solar research analyst in Europe, the Middle East and Africa. “[This] means these

offshore floating solar projects will also benefit from grid infrastructure that is already planned, if not built already. This would allow Dutch transmission system operator TNO and developers and asset owners to increase the capacity factor for these assets, without the need to invest in additional grid infrastructure.

“What makes the Netherlands stand out as a key offshore floating PV market is the fact that its government is clearly betting on this technology due to the need to drive innovation, solve critical grid congestion challenges and deal with land scarcity for large-scale solar development onshore.”

However, there are questions over the future of the Dutch solar sector, especially with regard to government support for projects such as floating solar. Last July, the collapse of the country’s government led to a snap election, which saw the right-wing Party for Freedom win more seats than any other party, although not enough for an outright majority.

While the party’s leader, Geert Wilders, has said he will not take the office of prime minister, as his party tries to form a ruling coalition government with several other parties, the Party for Freedom voted against the creation of a €35 billion fund to aid in the renewable transition last year. The prospect of a party sceptical of the need to decarbonise the country’s energy mix holding significant power in the Dutch government casts a doubt over the long-term health of the country’s solar sector.

France

France is Western Europe’s third-largest solar market, with around 20GW of capacity in operation, and 3.1GW of new capacity added in 2023. This was a record high for the country, exceeding the previous annual installation record of 2.8GW, set in 2021, and roughly tripling the annual installation totals of 2012-2019, which never exceeded 1.02GW during this period.

The French Renewable Association also has a number of ambitious targets for the solar sector, aiming to install 65GW of operating solar capacity by 2030 and 115GW by 2035, figures that are more ambitious than the NECPs submitted to the EU, and could help France reclaim its top-two spot among Western European countries.

Making solar an attractive investment destination has been a priority for the government, which hopes to encourage private investment into the sector to meet some of these targets. The government plans to offer tenders for 3.2GW of new solar projects each year, and while these tenders have been historically undersubscribed, the government granted tenders to 129 projects, with a combined capacity of 1.5GW, in September 2023, a record tendered capacity.

“The French solar sector is attractive to investors due to robust government support and clear regulatory frameworks,” explains Alejandra Pérez-Pla, regional manager of the Mediterranean at financial adviser Global Capital Finance, and maintaining this state of investor-friendly affairs could be vital if France is to meet some of these more ambitious targets.

“Opportunities for public-private partnerships and financial instruments like green bonds provide secure and targeted investment channels, making France a prime market for solar investment,” adds Pérez-Pla.

Other government initiatives include the passage of a law that requires all new car parks built with space for 80 vehicles to include solar panels and a law that mandates solar projects built on farmland to include an agrivoltaics (agriPV) element.

“The strategy to achieve 100GW of solar capacity by 2050 involves more than substantial investment in rooftop solar; it includes balancing utility-scale and rooftop solar installations. Innovations like floating solar panels and integrating solar infrastructure are considered to help mitigate land use issues,” says Pérez-Pla, highlighting the range of investments needed to meet these ambitious targets.

“Innovations like agrivoltaics and the use of non-conventional sites are crucial for scaling up France’s solar capacity,” adds Pérez-Pla, who is supportive of the potential of agrivoltaics to overcome this land-use challenge. “Community engagement and modernised infrastructure also play key roles in supporting the expansion of solar installations.”

However, Pérez-Pla concedes that the availability of connections to France’s energy grid poses a challenge for new solar deployments. As is the case in much of Western Europe, the speed with which new solar projects are being commissioned is faster than the pace at which the grid can be expanded and these projects connected to the grid, creating a frustrating wait for grid connections and preventing countries from meeting the targets they have set.

“The success of expanding solar capacity will also depend on simplifying regulatory processes and enhancing energy storage technologies to manage solar energy’s intermittent nature,” says Pérez-Pla, suggesting that parallel reforms of regulation and investment into technologies such as storage will be needed to modernise the French energy grid to facilitate the connection of new solar capacity.

“Overcoming these obstacles will require concerted efforts from the government, the private sector and local communities.”

Less mature markets

Beyond the big three in Western Europe, there has also been considerable growth in smaller solar markets, led by Austria, which crossed the 1GW threshold for the first time in 2022. The country expanded its total installed solar capacity to 6.2GW in 2023 and plans to reach 41GW of cumulative installed capacity by 2040.

The country’s Renewable Energy Expansion Act, passed in 2021, obligates Austria to meet 100% of its electricity consumption by 2030, and the act targets a renewable power output of 27TWh by this date, of which 11TWh will have to be produced by solar sources. To meet these targets, the national government has increased its PV subsidies considerably, almost sextupling financial support from around €110 million (US$118.5 million) in 2021 to €600 million (US$646.5 million) in 2023. The government also supports 700MW of new capacity installations per year through a contracts-for difference scheme.

However, this raises questions about the long-term viability of large-scale solar in Austria. A common feature of the more mature solar markets in Germany, the Netherlands and France is that solar projects are often lucrative investments for potential investors. These projects can generate a profit without relying exclusively on generous government subsidies, and the Austrian solar sector will also likely have to attract greater private interest to scale up its solar deployment in the coming decades.

“Look at the track record in countries where you don’t have a very developed permitting or even auction system, like in the east of Europe,” explains Naomi Chevillard, head of regulatory affairs at SolarPower Europe, who suggests that private interest is a necessary component to solar expansion.

“You have a lot of interest for power purchase agreements, completely private contracts between a buyer and a seller. That really shows the interest there is from the market to invest in solar.”

Belgium, meanwhile, added less new capacity in 2023 than Austria, commissioning 1.8GW of new projects, but its solar sector is much larger on the whole, with 9.9GW of capacity in operation. This is already in excess of the 8.9GW target in place in its latest NECP and, as has happened in Austria, this growth owes much to supportive government policies.

Between 2021 and 2022, the government implemented a “social tariff” to cover some of the energy costs for Belgium’s poorest citizens, which amounted to the government committing €600 million (US$651 million) to help grant energy access to those who would otherwise struggle to meet their energy needs.

The government has also deployed the Energy Effective Retrofit (ASTER) programme in Flanders, the Belgian region that accounted for 1.4GW of new capacity additions in 2023, that will see local social housing companies invest around €155 million (US$168.2 million) into a rooftop solar installation scheme, where local people will be charged just €0.2 (US$0.22)/ kWh for electricity consumed.

However, the long-term viability of many of these projects is unclear, considering Belgium is one of many European countries set to hold elections over the summer. In March, far-right party Vlaams Belang held a lead in the Flemish polls, with 27.8% of the vote, and the party’s members have already made their scepticism of renewables clear, calling for an abolishment of the Green New Deal in the European Parliament.

Should the party’s popularity continue, the shape of Belgian politics could come to resemble that of the Netherlands, raising many of the same questions that the Dutch solar sector will have to address, if it is to meet its targets. With such uncertainty in place, there is more emphasis than ever on answering the question that is asked of many smaller solar sectors, namely how can solar projects be made attractive for private investors, so money will continue to flow into the sector even as government support falters?