The world needs more renewables, and the scale of the task ahead remains daunting. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), solar and wind power will have to contribute to 70% of the world’s electricity production by 2050, up from just 1.1% and 2.2% respectively in 2019, according to Our World In Data. This deadline has left world’s national governments and energy companies just 27 years to fundamentally change the Earth’s energy mix, and avoid irreparable climate damage.

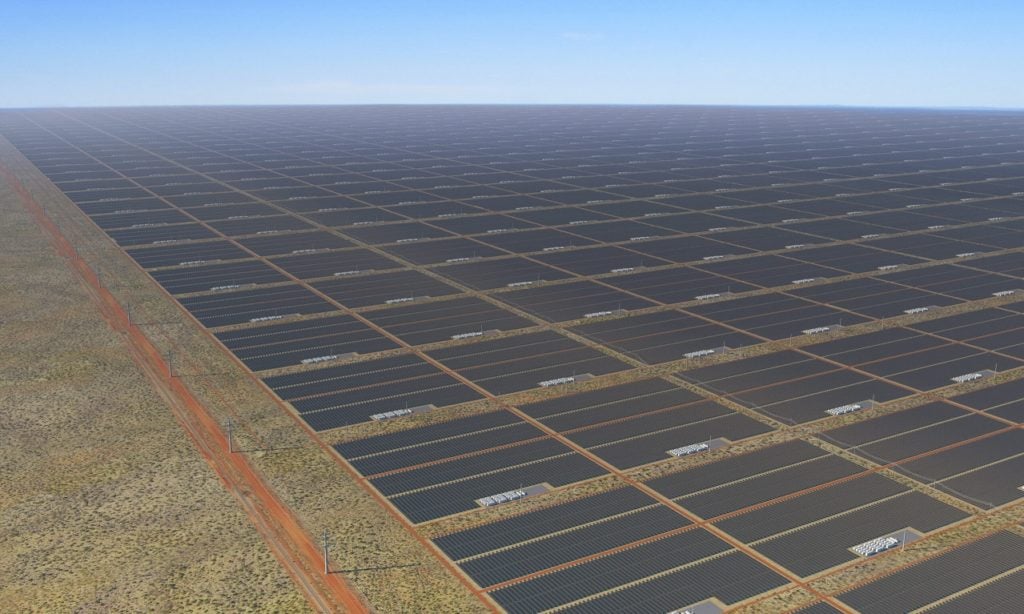

With that in mind, many countries and companies are investing in large-scale solar projects to meet this massive demand, and building gigawatt-scale solar facilities from scratch brings with them a number of administrative and logistical difficulties. To overcome these challenges, most developers have adopted one of three models of funding and ownership: direct involvement from a central government, support from a myriad range of private investors, or a combination of private bidding for government-sanctioned permits.

Unlock unlimited access for 12 whole months of distinctive global analysis

Photovoltaics International is now included.

- Regular insight and analysis of the industry’s biggest developments

- In-depth interviews with the industry’s leading figures

- Unlimited digital access to the PV Tech Power journal catalogue

- Unlimited digital access to the Photovoltaics International journal catalogue

- Access to more than 1,000 technical papers

- Discounts on Solar Media’s portfolio of events, in-person and virtual

While each approach brings benefits and drawbacks, from the decisive action of a single government to the complexities of multi-party investment, the uncertainty surrounding all of these approaches draws attention to the fundamental challenges facing large-scale solar power, raising the question as to whether such massive projects are simply too big to succeed?

Highly centralised efforts

The most obvious example of large-scale solar delivered by a centralised organisation is China, where the state’s stake in solar power companies means that the government is often directly involved in the commissioning and constructing new projects.

For instance, the government announced plans to build new solar facilities on land with “low ecological value,” a move that could generate significant profit margins by constructing in-demand power facilities on historically unused land. The government’s instruction also sidesteps some of the permitting and environmental obstacles that exist in other countries, where stakeholders such as environmental agencies and local authorities can push back on such sweeping policies.

The relative ease with which the government can push through new projects has contributed to China’s dominance of the global solar sector, and is compelling evidence for the benefits of such a centralised approach.

According to BP’s Statistical Review of World Energy, China dominated global solar capacity in 2021, leading the world with 306.4GW of installed capacity, more than six times that of India, which boasted the second-most capacity in the world, and more than one-third of the global capacity of 843.1GW.

From January to May 2023, China added 61.2GW of capacity. According to previous statistics released by the National Energy Administration from January to April, the newly added PV capacity during the first four months this year was 48.3GW, indicating that the installed capacity added in May alone was nearly 13GW. The National Energy Administration in July also announced that China’s total installed solar PV capacity was 471GW as of June 2023.

State-owned projects beyond China

This governance structure has also been effective in other parts of the world, and could have encouraged collaboration and cooperation with other countries whose solar sectors are similarly driven by national interest.

In March, the China Energy Engineering Corporation announced a bid to build a 1GW floating solar facility on Zimbabwe’s Lake Kariba, in conjunction with the Zimbabwe Power Company, a move dubbed a “great idea” by Anthony Phiri, director of environmental management at the Renewable Energy and Climate Change Center, at the Harare Institute of Technology in Zimbabwe.

“[Projects like these] don’t require land space, utilise unused water space, generate additional electricity, reduce evaporation and is good for large electricity sources as the panels are effectively cooled by moist winds,” adds Phiri.

Both companies are owned by their respective national governments, and such decisive action as building large-scale power projects quickly may only be possible where governments can mobilise resources quickly for a single purpose.

“Certainly, I would support such an initiative from China or any other country,” says Phiri, explaining that this model of ownership can help deliver tangible benefits for an energy infrastructure. “If the China Energy Engineering Corporation proposed the Lake Kariba solar project, I would you welcome this kind of involvement from a Chinese company in Zimbabwe’s energy mix.”

Complex private ownership

The influence of a single, influential government has limitations, however, namely that the influence of a government is often limited to areas within its borders. Some of the largest solar power projects in the world span multiple borders, and involve several stakeholders, and could exert more significant influence over the solar sector as a result.

The most obvious examples are Sun Cable’s Australia-Asia PowerLink and Xlinks’s subsea power line, two massive transmission projects that were commissioned with the aim to generate solar power in Australia and Morocco and deliver energy to Singapore and the UK, respectively.

The two projects have a total capacity of around 30GW and are thought to cost around US$40 billion, vast projects in terms of both their investment potential impacts on the countries in which they operate. PowerLink was planned to cover 15% of Singapore’s energy needs, while 10,000 new jobs will be created during the construction stages of the Xlinks project.

However, there is a very real opportunity that, without the oversight of a central government, these projects can be so big as to become unwieldy.

“The majority of them never get anywhere,” says Glenne Drover, secretary of the Melbourne office of the Australian Institute of Energy, speaking about private projects whose ambition far exceeds their capacity to deliver. “In that 17 years [I worked in the Victorian government] I would have met 1,000 companies who felt that we’re going to change the world, or at least Australia, and the majority never did.”

Pressure on private owners

Of course, the multi-faceted nature of each project has led to similarly complex challenges. Drover argues that private owners need to have total clarity of the direction and goals of such a project, as they are singularly responsible for providing vital funding.

“You need patient investors that are prepared to provide that seed funding and continue to provide it because it’s like a house renovation, it will take twice as long as expected [and] it will cost twice as much as expected, and that was part of where the Sun Cable ran to a point where it was beginning to fail to meet the deadlines,” says Drover.

A lack of coherency contributed to the recent downfall of Sun Cable, which saw joint venture partners Mike Cannon-Brookes and Andrew Forrest fall out, and the latter sold his share in the company to the former, leading to questions as to the future of the project.

Indeed, the company’s new backer, David Scaysbrook, of Quinbrook Infrastructure Partners, is reported to be “agnostic” about the project’s work in Singapore, and open to the idea of expanding the company to work with wind power, in addition to solar.

While these are not step backs per se, the emphasis on Singapore and solar power were fundamental parts of the initial Sun Cable offering, and to have such aspects challenged, or at least reconsidered, by a new ownership group highlights the uncertainty that can stem from variations in leadership, an aspect of private ownership models.

A more flexible approach

Combining these elements of state-sanctioned projects and work driven by private investment is a model in which a government offers permits for various private projects in rounds. The model has been used across the energy industries, and has seen some success in South Africa, in the form of the Renewable Energy Independent Power Producer Procurement (REIPPP), which has awarded permits to six generations of projects since 2011.

The flexibility of such a model means that projects are less restricted by the narrow interests of a single government, or the investors and shareholders behind a multi-billion dollar project, who may insist that their money is invested in a particular manner.

Even Phiri, who is broadly supportive of state ownership of energy projects in Zimbabwe, is aware of the limitations of the model, and the benefits of bringing multiple stakeholders into a project’s management and financing.

“I don’t think Zimbabwe is getting closer to its clean energy at the moment,” says Phiri. Despite renewables accounting for 72% of Zimbabwe’s energy demand in 2019, 96% of this came from biofuels, with neither solar nor wind accounting for more than 1%, according to the International Renewable Energy Agency.

“Depending on the subcontractors state-operated companies can design, build and operate large-scale solar projects quickly and effectively,” adds Phiri, pointing to the benefits of some private ownership in renewable power generation. “Monitoring and evaluation can be done by an independent company in a fair and transparent manner.”

Ambition and oversight

This flexible approach also allows the government to benefit from the long-term oversight afforded by a government with the ambition provided by a private enterprise. Drover notes that these groups often operate different projects with different levels of proficiency, and combining these groups into managing a single facility could deliver benefits that neither could achieve alone.

“There are some things government does well, and there are these sorts of projects that have this high risk and need this early work done [and they’re] not something governments do particularly well,” says Drover, pointing to Sun Cable in particular as a project that a government would struggle to implement.

Using the example of REIPPP, the body doing the funding – in this case the South African government – is then able to alter its priorities and preferences for projects as market conditions change, rather than be locked into a fixed multi-year commissioning and construction process.

Considering how quickly the solar sector moves, particularly with regard to the implementation of new technologies and fluctuations in electricity prices, it can be of great benefit to reassess and reconsider priorities regularly. The fifth REIPPP bid window, completed in October 2021, saw the government grant funding to 13 solar projects, each with a capacity of 75MW, for a total of 975MW.

The sixth bid window, meanwhile, saw funding granted to just six projects, but with a capacity of between 120MW and 240MW, for a total capacity of 1GW, a move which suggests that the government is more interested in supporting a small number of more powerful solar farms, rather than a greater number of small-scale projects.

An incomplete answer

While the flexible timeframes of funding rounds are a benefit, there are other ways in which the REIPPP model has led to greater uncertainty. In the latest bidding round, only solar power projects were awarded funding, with no wind power projects receiving investment.

While this was encouraging news for the solar sector, the result contradicts South Africa’s own interest in wind power; prior to the award of the funding, the government doubled the total capacity wind developers could apply for, from 1.6GW to 3.2GW.

Indeed, the government plans to meet 15.7% of the country’s energy needs from wind power by 2030, compared to just 10.5% of this need met by solar, long-term plans that do not align with the most recent bid awards. With IEA figures suggesting that wind and solar collectively meet just 5% of the country’s energy needs today, the government’s reluctance to invest in wind power, and not replace this with greater solar funding, is a concern.

This is also to say nothing of the growing interest in direct private investment in South African solar, bypassing the state-sponsored aspect of REIPPP altogether.

Ultimately, it may be impossible to determine which of these models is simply ‘the best’, and instead focus on which is likely to be the most effective considering the specifics of the project in question. In some parts of the world, state-operated companies can mobilise more resources to quickly construct large-scale projects, whereas in others, a range of public and private investors could help stabilise solar power generation at a time where the market is growing, and changing, faster than ever before.

As a result, commissioning and operating large-scale solar facilities is a process of assessment and improvement, and Drover points out that this process of learning is a key aspect of any such energy project.

“We’re still learning,” says Drover. “We’ve got a lot of people, many thousands of people, and everybody’s still learning. The mega-project people are learning … the billion-dollar hydrogen plan people, they’re all learning.”