Last week, Danish independent power producer (IPP) Better Energy postponed the deployment of a 3GW solar PV portfolio in its home country, blaming “lagging” demand for renewable power capacity in the country.

While aligning power supply with demand is itself nothing uncommon, the scale of this portfolio, and the extent of its postponement, are notable, as Better Energy expects to commission the portfolio after 2030.

Unlock unlimited access for 12 whole months of distinctive global analysis

Photovoltaics International is now included.

- Regular insight and analysis of the industry’s biggest developments

- In-depth interviews with the industry’s leading figures

- Unlimited digital access to the PV Tech Power journal catalogue

- Unlimited digital access to the Photovoltaics International journal catalogue

- Access to more than 1,000 technical papers

- Discounts on Solar Media’s portfolio of events, in-person and virtual

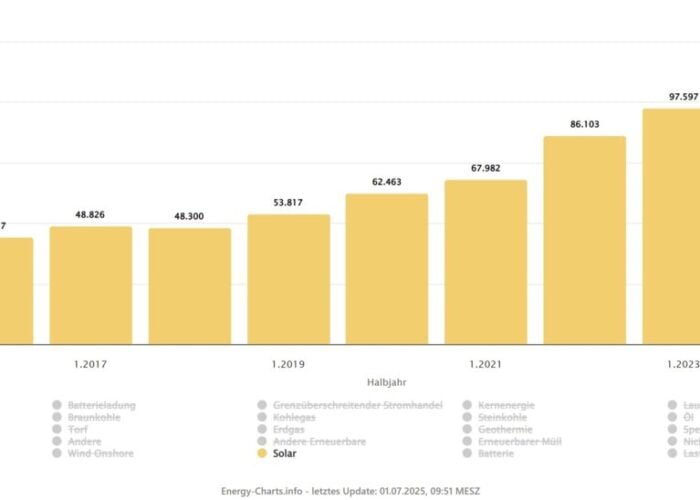

The fact that both Better Energy itself, and Denmark more broadly, have made significant progress with their renewable power deployments in recent years, also suggests that, as the clean energy transition takes place, demand for new renewable power projects could decline sharply. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), wind and solar PV accounted for over two-thirds of the country’s total electricity generation, with coal and oil responsible for about 7.5%, while Better Energy generated more than double the electricity from its PV plants in 2023 than in 2022.

“We have very large projects, and we’re very aware that we need to match our production to expected demand in the regions [where we’re active],” Christian Bergmann Mølgaard, Better Energy vice president and head of communication told PV Tech Premium this week. “Some of it [the shift towards greater supply than demand] has happened very quickly, and more quickly than we had anticipated.”

Bergmann Mølgaard noted that, while Better Energy has not yet announced which of its projects in particular will be subject to delays, the company’s work in general has been affected by “the expected rise in [electricity] demand is moving slower than expected”.

Making financial sense

The primary motivating factor for these postponements is financial, namely that new projects will struggle to sell electricity at a profit if demand for clean power continues to be low. Minimising financial risk has become a key consideration for investors in the solar sector this year, and Bergmann Mølgaard was keen to stress that the clean energy transition must progress in a manner that makes financial sense.

“[The growth of renewable power capacity has] affected the investor environment very quickly, because the tendency in the investment market is that when there’s uncertainty, you pause,” said Bergmann Mølgaard. “Not necessarily to stop, but you hesitate, and you’re less likely to follow through as usual.

“Part of that will fix itself once the market consolidates, and in that regard, I don’t think this is very different to a lot of other industries; we produce a product, and make factories that produce that product, and obviously if we don’t have customers, we don’t build another factory.

“That can be hard to understand because its power—and we need a lot of power—but it also has to be tied to development and demand, like anything else on a marketplace,” he added, suggesting that energy generation should not be thought of as race to install as much capacity as possible, but one that must take into consideration financial realities.

Sensible timing, not mere passivity

However, there is a risk that solar deployment can become almost passive, with investors and developers stuck waiting for favourable economic conditions before committing to investments in large-scale projects. Bergmann Mølgaard, however, did not describe Better Energy’s postponement in this manner.

“‘Passivity’ is the wrong word, ‘timing’ is the word we use ourselves,” he said. “It is not fully in our control, but it’s not fully out of our control either. In order for a project, or a green hydrogen facility, to be built, you will need an expectation of a massive amount of additional green energy production, so we play a key role in saying ‘this is the foundation for any of the other things to happen’.”

“If we didn’t have any projects, you’re looking at something that’s more or less impossible to realise, because you need a lot of affordable green electricity to make these transitions happen.”

Bergmann Mølgaard mentioned this idea of multiple, plural, “transitions” often, suggesting that the world’s energy mix will not necessarily benefit from, for example, replacing all oil production with solar power generation, but that a mixture of technologies and scales of operation will be necessary to make the world’s power generation more sustainable. This is reflected in the growing number, and scale, of hybrid renewable power projects in various stages of development around the world, including Avaada and the Gujarat government’s plans to develop a massive 6GW solar-wind portfolio in India.

“We’re looking at timing and [deploying] green energy in the right place at the right time,” added Bergmann Mølgaard, whose approach of considering multiple technology types can be applied to the different economic and political factors that determine the viability of a project. “There are a lot of different things that determine exactly when the demand will come, and there are some things that, on a more governmental level—on both an EU and national level—they can look at some of the subsidy schemes that are in effect right now and ask ‘what are we doing to help drive the demand towards green energy?’”

Working in tandem

“The transmission system operator (TSO) has no desire to put 3GW of solar on the grid too early,” continued Bergmann Mølgaard, who suggested that investors and IPPs would also benefit from working more closely with bodies such as TSOs. I think it’s more clear than ever that we need to collaborate, we need strong partnerships and we need to know what each other is planning.

“[Previously] if we had the permits in place we could build, as there was demand all over; but now, there will be regional demand, and I think the main things in terms of the political shift, should be in terms of driving demand towards flexibility and flexible consumption. Those things are massively important, because no matter how much we put on the grid, we won’t fix the variable nature of renewable energy.”

When asked about what kind of projects could benefit from this more joined-up way of thinking, Bergmann Mølgaard was keen to stress that large-scale projects can likely be the most flexible, as they have fewer administrative moving parts than small-scale or decentralised projects.

“By far, the easiest type [of project to commission quickly] is large-scale projects,” he said. “Then you’re handling one set of stakeholders, and one grid connection and one dialogue with a TSO. I think if you had 200 different projects, ranging from, say 5-50MW, it would be almost impossible to [commission] that strategically in the long-run.”

Perhaps it is this type of thinking that led Better Energy to look to build 3GW of new solar generation capacity in Denmark in the first place; and this kind of thinking that has made the company confident in postponing the commissioning of this capacity until economic conditions are more favourable.