India is in the midst of a frantic large-scale solar tender bonanza that seeks to emulate China’s colossal PV deployment. Doubters say the plans are ill-timed given the Indian sector’s stuttering at the hands of various trade disputes and additional taxes, but the hunger for new capacity could be satiated through a promising new outlet. A 10GW consultation exclusively for floating PV has been issued by the Solar Energy Corporation of India (SECI) and it is conceivable that no such plans would be on cards had it not been for the completion of a humbly sized but strategically significant project in the southern state of Kerala. Given its size and potential, India was a relative latecomer to the multi-gigawatt solar markets of the world stage and its module procurement remains stuck at the low end of product ranges on offer. However, floating solar, the up-and-coming saviour of PV’s traditional land constrictions, could turn out to be a technology on which India is amongst the early adopters on a grand scale.

With plenty of hydroelectric reservoirs in certain states and a vast number of manmade ponds used by thermal power plants, there is no shortage of water bodies to keep India’s floating pioneers busy. But first, the industry needed proof that such projects could work in India, which is seen by many as a somewhat tricky market.

Try Premium for just $1

- Full premium access for the first month at only $1

- Converts to an annual rate after 30 days unless cancelled

- Cancel anytime during the trial period

Premium Benefits

- Expert industry analysis and interviews

- Digital access to PV Tech Power journal

- Exclusive event discounts

Or get the full Premium subscription right away

Or continue reading this article for free

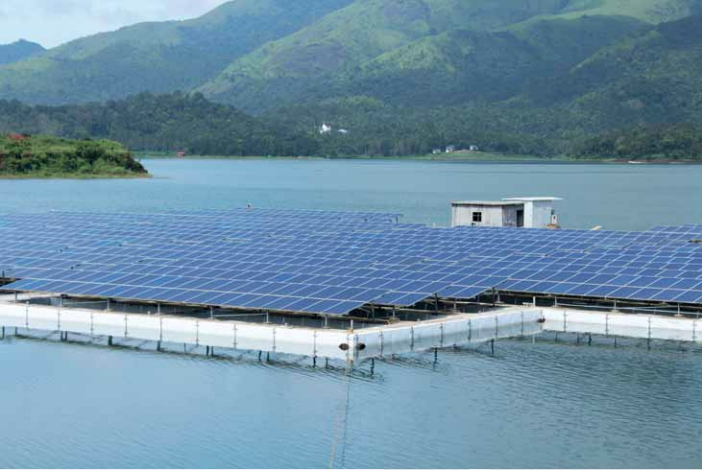

No doubt under the watchful eye of the central government in 2015, one state utility, Kerala State Electricity Board Limited (KSEBL) went about tendering for a 500kW system at the Banasura Sagar reservoir in Wayanad, which now stands as the largest floating PV plant in India following grid connection in late 2017. Local firm Adtech Systems, based in Trivandrum, won the tender and proceeded using modules assembled by Telangana-based manufacturer Radiant Solar and 32kW string inverters made by ABB, a firm that is well established in India and has service support locations in the city of Bangalore, not far from the project location. Two other major contributing firms were Floatels India and Regen Power, which is based in Western Australia.

The first 2018 edition of PV Tech Power is now available, including a 'Floating Solar: Special Report' and a lengthy discussion of this burgeoning technology from the Solar Energy Research Institute of Singapore (SERIS).

KSEBL was not primarily looking for payback, says Raveendran T. Nair, vice president, projects, Adtech, because the aim of the floating plant was more to act as a technology demonstrator. As the utility of Kerala, a green and tropical state with plentiful rainfall, KSEBL was also looking to make the most of its many reservoirs. Moreover, as one of India’s most densely populated states, Kerala has expensive land, which gave added impetus to the search for viable alternatives to land-based projects. Likewise, Nair believes the utility had no worries about the long-term outlook for floating PV tariffs once the technology becomes widespread in India, given the extreme drops seen in utility-scale ground-mount prices across the country in recent years. With this confidence, the stakeholders in the Wayanad project chose to focus on using highest quality materials and components to make it a successful proof-of-concept undertaking. Total project cost was INR92.5 million (~US$1.46 million).

While the surrounding area was scarcely populated before the government procured the land and built a dam to support the Kakkayam hydroelectric power project in 1979, many locals were displaced when the dam project was started. It remains the largest earth dam in India and the second largest in Asia. Regular dams are made of concrete, whereas this is made of an earth embankment that is nearly 100 kilometres in length, adds Nair. Now the site attracts tourists drawn by many surrounding waterfalls and smaller lakes and adventure sports.

To test project viability in this location, a scaled down 10kW version of the system was installed in the same reservoir by Vaatsa Energy, a young start-up company with technical support from Floatels, says M.R. Narayanan, chairman of Adtech Systems and managing director of Floatels India.

Bar a few minor cuts, the next 500kW was completed without accident although Nair says the main challenge was constructing the floating platforms due to a lack of suitable facilities on site. Progress slowed down for this period due to the site’s lengthy distance from any main industrial base. As a comparatively new reservoir, the soil around it was soft, meaning that mechanised equipment could not be taken near to the shoreline. Such difficulties would be less likely in other locations around industrial or thermal power plants, adds Nair.

The solar plant will not affect the quality of the water in any way, Nair assures, claiming that there are no effluents from the equipment and even forecasting that the structure might improve fishing figures by providing a section of water that is shaded and therefore of a lower temperature than the rest of the reservoir. The environmental effects of floating solar are certainly a concern in the industry and it is not just water quality that causes concern. The impact of a sudden lack of sunlight on biodiversity in these water bodies is often raised as a potential problem, but has not yet been well-studied in the context of floating solar as far as PV Tech Power is aware.

The system

The project involves fibre-steel-based floats that were designed with ferrocement, which involves applying reinforced mortar or plaster over layers of metal to create a hollow structure, making the project very stable, says Narayanan. “Our company has been specialised in making ferrocement platforms and floating structures for the last 20 years,” he adds. “They are guaranteed for a 50-year life.”

Unlike similar materials, the ferrocement uses either welded mesh or expanded metal to make the metal to mortar ratio higher, so that if taking a cross-section, the metal content will be higher than in regular concrete. Nair is surprised that it has not become a more popular material since it is thin, lasts well beyond 50 years and requires little maintenance.

“With steel it tends to rust – you have to scrape and bend it and all that, whereas this needs no such maintenance,” he adds.

Each floating platform has one string inverter. The 415V from these inverters is fed to the ELT 415V switchboard, which is then transformed to 11kV. An 11kV XLP underwater cable, from major Indian cable supplier APAR, has been laid along the bed of the reservoir to the shore. Many other floating solar designs have the cables above water, but in this case the reservoir attracts many tourists for boating so underwater cabling was required to prevent any hindrance to those activities. Adtech also felt that it was more aesthetically pleasing to have the cables hidden.

Generation benefits

Being located on top of a hydro plant means the solar generation can support daytime peak load and more hydro power can be reserved for the evening peak, says Nair. It’s a major opportunity, particularly in Kerala, given that almost all of the state’s locally generated power comes from hydro already. The state relies on energy imports from other states for a significant portion of the rest of its power mix.

“The water available in these generating stations in the reservoir is not sufficient for running these hydro generators for 24 hours, 365 days so they have to stop the generators over substantial periods,” adds Nair. “So instead of that they can run the hydro plants during night and you can utilise the solar generation during daytime.”

The hydro plants also guarantee that transmission infrastructure is already available in close proximity to any co-located floating PV plant. Nair describes this as a “win-win” situation.

From a logisitics perspective, while the Banasura Sagar reservoir is remote, it was still relatively accessible by lorry, being located just 20 kilometres from the Calicut- Mysore-Bangalore road.

O&M

Adtech was awarded the EPC contract for the project by KSEBL as it put in the lowest price bid, and under this contract it must perform O&M services on the plant for a two-year period; subsequently, it has to maintain the equipment in case of any faults for another four years.

Cleaning the plant is easy given regular rainfall on location for nearly six months of the year, which naturally washes the panels. Dust, which can cause soiling of the panels, is also minimal at the location. Of course there will still be occasional build ups of sediment on the panels and the two-man team uses long handheld mops to clean them. They brush using rainwater as it falls or pump water onto the panels from the reservoir itself. An ABB remote monitoring system keeps tabs on each string feeding the inverters and can record energy generation statistics.

Tenders

With the successful completion of the project, the government is now scanning the rest of India to see where the opportunities lie and how much appetite there is. Besides hydro dams, industrial units and thermal power ponds are the most obvious targets for now and Nair says they are a multi-gigawatt prospect.

Since the project was completed, Adtech has received enquiries for dozens more megawatts of projects, Narayanan adds, which demonstrates a desire to try out this technology already at this early stage.

To drive the technology further, Nair suspects that KSEBL will now go down the tender route to procure more floating PV, although he expects there to be strict prequalification requirements.

Anchors and huge water level variations

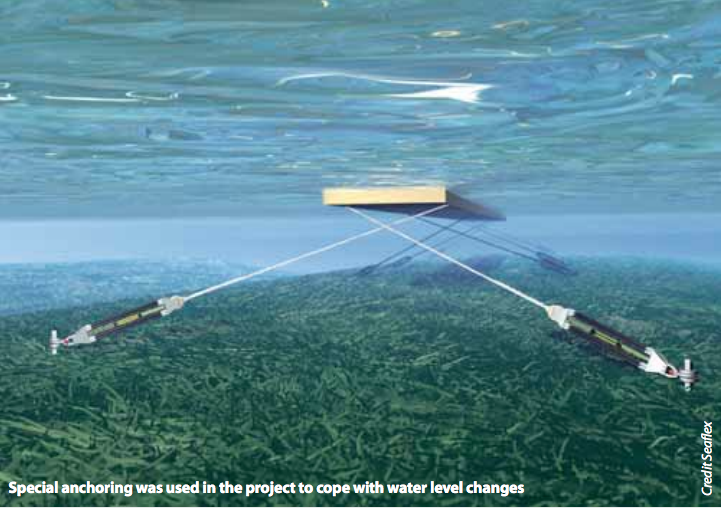

The main challenge for the project was a water level variation of up to 25 metres between summer and monsoon seasons, says M.R. Narayanan, chairman of Adtech Systems, so the firm had to procure and design special anchoring systems to ride the variations as well as high-speed wind conditions while lasting 25 years.

Swedish specialist in mooring and anchorage systems, Seaflex AB, supplied the Wayanad project (see picture above). Company CEO Lars Brandt says that harbours and marinas from around the world have done business with Seaflex to make use of its floating marine structures. A Seaflex representative visited the Indian project in March 2017 to survey the site and surrounding area. Based on these details Seaflex designed the anchoring system and Adtech installed it.

Withstanding the huge water level variations was a key challenge. For this, the anchoring system uses a patented polypropylene rope assembly where the ropes, tied to the floating structure on the surface of the water above and to the anchors on the bed of the reservoir below, can stretch to roughly 70% of their initial length. A total of eight anchors were used to allow the floats to withstand wind from several directions and the slight stretching of the elastomer rope can alleviate the wind forces.

The depth of the reservoir at the plant location is around 35 metres when full. As the water levels rise and fall with seasonal rains, the ropes can stretch or contract as necessary. The stretching rope means that once assembled, installed, tested and put in place it operates automatically without requiring any external forces.