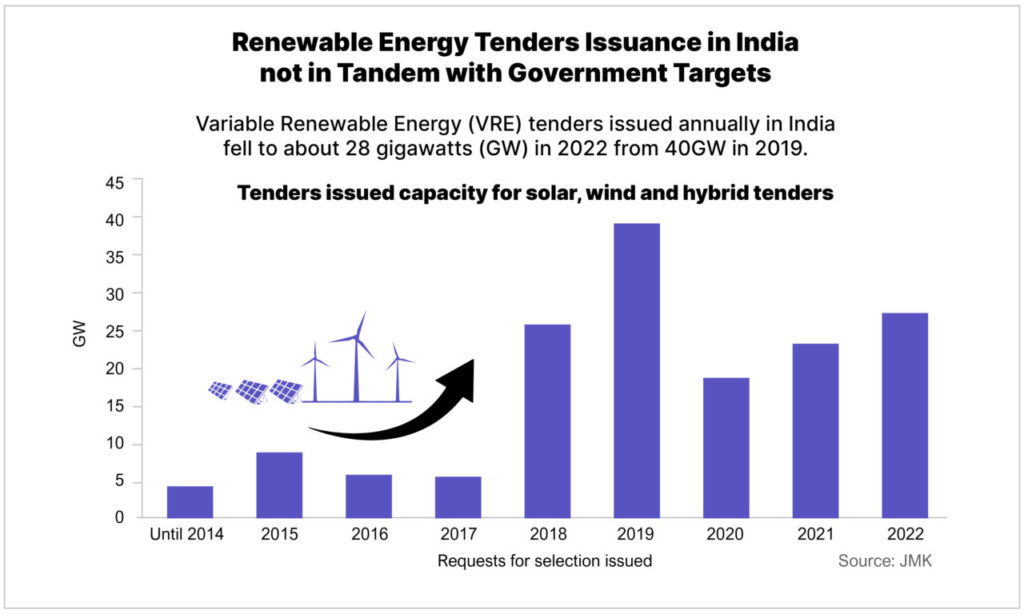

India needs to issue more renewable energy tenders if it is to meet the government’s target of 450GW of installed capacity by 2030, as the changing preferences of distribution companies have seen less uptake and states have been inconsistent in fulfilling purchase obligations.

According to a joint report from JMK Research & Analysis (JMK) and the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), 2022 saw 28GW of renewable energy tenders issued in India, falling from 40GW in 2019. Co-author of the report, Vibhuti Garg said: “To reach the 2030 target, India will need to open renewables tenders for at least 35GW annually.”

Unlock unlimited access for 12 whole months of distinctive global analysis

Photovoltaics International is now included.

- Regular insight and analysis of the industry’s biggest developments

- In-depth interviews with the industry’s leading figures

- Unlimited digital access to the PV Tech Power journal catalogue

- Unlimited digital access to the Photovoltaics International journal catalogue

- Access to more than 1,000 technical papers

- Discounts on Solar Media’s portfolio of events, in-person and virtual

One of the central reasons for the drop-off in variable renewable energy tenders has been the changing tastes of distribution companies (DISCOMs) away from straight solar and wind projects towards wind-solar hybrid or solar-plus-storage projects.

JMK said that the shift is due to the inherently intermittent generation of solar and wind assets, whilst hybrid projects or those paired with storage can offer more stable and consistent power which is more attractive to offtakers. However, these projects are more costly and often the economics are not viable without support from the government.

Tenders have also been inconsistently applied across the states in India, which has contributed to the decline in national additions. Renewables Purchase Obligations (RPO) apply to all states, but uptake has been varied; ome states have fully met their requirements whilst others are being wavied, carried over or relaxed.

Prabhakar Sharma, consultant at JMK Research said: “Renewable energy-rich states like Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh have already achieved their RPO targets. Hence, tender issuance from these states has slowed significantly despite the still-free interstate grid transmission access for variable renewable energy.”

PV Tech Premium spoke with analyst firm Bridge to India last month, which said that all states would need to be obligated to meet their RPO targets if 2030 solar targets are going to be met. As it stands, just five have publicly agreed to the targets.

Developers have also been participating less in tenders, the report said. The effects of the Approved List of Models and Manufacturers (ALMM) and basic customs duty (BCD) policies have pushed prices up as projects have struggled to procure modules, which has in turn lessened developers’ willingness to expose themselves to risk and bid aggressively for tenders.

The government recently announced plans to relax the ALMM for two years to allow a broader spectrum of companies to supply PV projects in India.

In terms of solutions and pathways to reaching the 2030 targets, the report suggested that tender authorities need to take a harmonious approach to considering the desires of both developers and offtakers (DISCOMs) in designing their tenders and tariffs. Prices must be kept in check whilst still fostering competition.

Last month PV Tech covered another report from IEEFA that pointed to the investment potential of hybrid solar projects and corporate PPAs in the future for India.

RPOs must also be enforced firmly across all states, the report said, with penalties for failure introduced, as well as payment assurances to assuage developers’ fears of delayed payments on tender projects.

If these measures are enacted, Vibhuti Garg said that 35GW annual capacity additions are possible, though it remains ambitious.