A chaotic period of policy and trade tariff disruption in the US has created a complex maze of new rules and regulations for developers to navigate. Jonathan Touriño Jacobo recaps the key developments and assesses how they are impacting America’s solar supply chain.

To say that it has been a busy time for the US solar industry lately would be an understatement. This is especially true at the policy and tariff level, where many changes have already occurred or are imminent.

Try Premium for just $1

- Full premium access for the first month at only $1

- Converts to an annual rate after 30 days unless cancelled

- Cancel anytime during the trial period

Premium Benefits

- Expert industry analysis and interviews

- Digital access to PV Tech Power journal

- Exclusive event discounts

Or get the full Premium subscription right away

Or continue reading this article for free

From the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBA) to the antidumping and countervailing duty (AD/CVD) cases, passing by the UFLPA, the “reciprocal” tariffs or Section 232, there are many pieces ofthe puzzle that have and will affect the US supply chain of solar products. This article will provide an in-depth examination of each piece of legislation or tariff that must be considered when securing the supply of new products, whether manufactured in the US or elsewhere. Especially with the 4 July 2026 and the end of 2027 deadlines looming.

UFLPA can come into play at any time

The Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA) was signed by US President Joe Biden on 23 December 2021 and went into effect in June 2022. The legislation was enacted as the US response to China’s systematic use of forced labour against Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR).

The UFLPA creates a “rebuttable presumption” that any goods mined, produced, or manufactured wholly or in part in the XUAR, or by entities on the UFLPA Entity List, are made with forced labour and therefore prohibited from importation into the US under Section 1307 of Title 19 of the US Code.

When it was implemented in 2022, the US Customs and Border Protection Agency (CBP) detained US$709.9 million worth of PV shipments, which represented around 2GW of solar modules.

“The first two years were marked by very high levels of product detentions. Suppliers had tremendous difficulty getting their product released. It took many months and, in some cases, cost suppliers hundreds of millions. Just the cost of having their product sit in bonded warehouses was enormous,” says Christian Roselund, senior policy analyst at Intertek CEA.

Since then, most of the biggest suppliers have been able to navigate the UFLPA, explains Roselund; however, he adds that some companies have never seen a big return on shipments.

Even though the detention of goods in the electronics sector remained at a low level this year, there’s nothing preventing this from changing, as seen in August 2025, with the detention of solar cells from the Korean company Hanwha Solutions under suspicion of use of polysilicon produced under forced labour in Xinjiang.

That shipment was eventually leased, as told by Qcells’ CTO, Danielle Merfeld, to PV Tech: “We’ve demonstrated effectively to the enforcement agents that we were in compliance with all US laws.”

Although the solar cells were eventually released, this generated a nearly two-month hold on the goods before they were allowed into US soil, and in November it emerged that Qcells had been forced to furlough staff in its US facility as a consequence of the customs issues. Obviously, every case is different, but the enforcement of the UFLPA is still present more than three years later.

“This year, it stayed at a low level for the electronics sector. It could change at any time. We’re getting the impression that the Trump administration is just now starting to decide what it wants to do with UFLPA,” explains Roselund.

Trump’s tariffs have not forced a giant shift in manufacturing

Unlike other trade tariffs, Donald Trump’s tariffs, which were unveiled at the beginning of his second term as US President, have targeted every country. Since the first iteration of the tariffs in April 2025, they have been reduced for most countries and have become less impactful, as nearly every Southeast Asian country, except Laos, has a 19% tariff. This will still drive costs and prices up, explains Roselund, but this will be the same for every country, which doesn’t necessarily give any advantage to one over the other.

“It’s not something that is really forcing these giant shifts in manufacturing the way that AD/CVD is,” Roselund says. “The big producers, including the Chinese producers, can absorb some of these tariffs and duties to stay in the market and still have a healthy margin.”

Although not tied to the tariffs set by Trump, there is another element regarding tariffs in general that the administration could be considering in the future: trans-shipment—the process that moves goods from one country to another before reaching their final destination.

With parts of the supply chain being built across different countries, this could impact the final price of imported wafers, cells, or modules, potentially adding a further 40% tariff on top of the ones already set for each country.

AD/CVD: from one country to another

Over the years, the solar industry has faced several antidumping and countervailing duty (AD/CVD) investigations, which have led to the shifting of solar product manufacturing from one country or region to another.

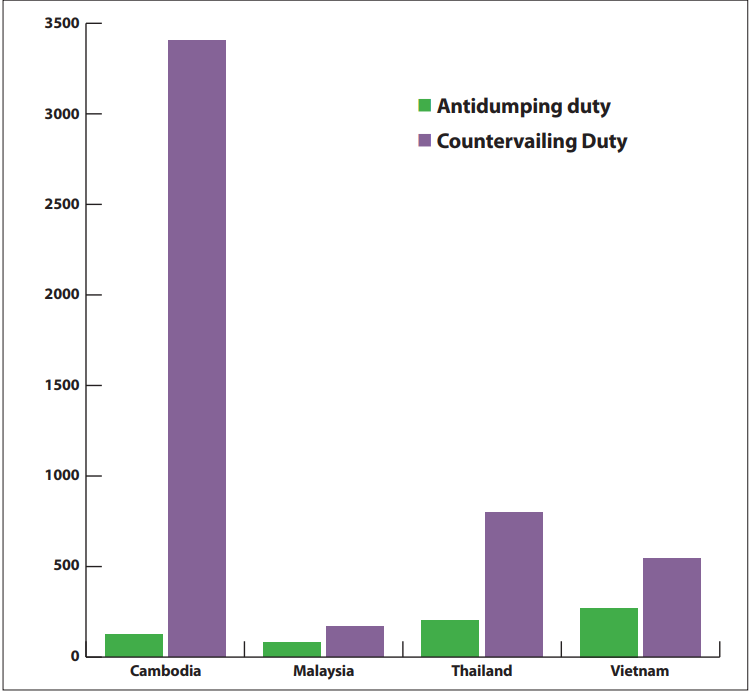

The latest example of this is the tariffs that were imposed on four Southeast Asian countries—Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia and Cambodia—with very steep rates for almost every market (Figure 1). Aside from Malaysia, all other countries ended up with tariffs higher than 100% (in the case of Cambodia, rates of up to 3,400% were imposed), which basically meant that the price of solar cells from these countries at least doubled and shut down the supply of capacity.

“AD/CVD cases, in most situations, effectively cut off supply from the countries that are under AD/CVD orders for those products,” says Roselund.

A similar fate is expected for the ongoing investigation involving India, Indonesia and Laos. The US Department of Commerce initiated an investigation in August, with preliminary determinations for the CVD investigation expected any day, while the AD investigation is anticipated to be completed by the end of the year.

“We expect the next three countries to receive similarly high rates, in the tripledigit range, compared to what most of the [other] countries received. Because of this, we expect that supply will be cut off. Already, clients are not planning to buy supplies after the preliminary duties take effect,” adds Roselund.

But even before the preliminary determinations are released, companies are already wary of the possible tariffs and how this could increase the price of modules.

“I would say there are concerns with signing contracts with supply chains that come from countries that are going to be impacted by the latest AD/CVD petition that exposes the buyer to those duties,” says Mike Hall, CEO at Anza.

Hall adds that currently, the focus is on buying products that are already in the US. “That’s where our customers want to go first,” he says. “There’s not as much inventory as there was, but there are still pockets of inventory available, and a significant number of the transactions that we’re doing with customers now are focused on that, because that reduces risk.”

With a decision on both investigations expected to be released by the end of the year, the focus is already on who could be the next target of an AD/CVD investigation. This time, the country that could be involved is much closer to Europe than those affected so far, as Turkey is taking advantage of the ongoing case, says Roselund.

“The winners of the last AD/CVD session are the losers of the next case. Right now, Turkish manufacturers are cashing in on their ability to serve the US market. We expect there will be a case filed against Turkey next year, as Turkey is the largest remaining source of crystalline silicon cell imports not yet subject to AD/CVD duties,” adds Roselund.

OBBBA’s negative impact on US manufacturing

On 4 July 2025, Donald Trump signed into law the One Big Beautiful Bill Act—more commonly known as OBBBA or OBBB—which repealed several tax incentives that had a significant impact on the renewables industry, although to a lesser extent for energy storage.

The impacts of the bill on the US solar industry as a whole, the residential market and energy storage were the focus of the previous issue of PV Tech Power, and as such, will not be explored further here. However, one consequence that has become clearer since July is that it has made the development of projects more complicated.

“[What] The OBBB has broadly done is force people to start projects earlier, and force companies to deploy capital earlier, which is painful,” says Hall.

The main factor here is the foreign entity of concern (FEOC) rules, of which the ownership and material assistance cost ratio is causing most concern, adds Roselund.

The material assistance cost ratio determines whether a project is eligible for tax credits, based on the total cost of all manufactured products and the proportion of that cost that was non-FEOC-compliant. This will take effect for projects that begin construction in 2026, with an initial threshold of 50% of products required to be domestic and increasing by 10% every year until 2029.

It also raises concerns about its impact on the domestic manufacturing industry, about which Hall says: “This bill is definitely bad for US manufacturing.”

Considering that the global supply chain is still heavily reliant on the Chinese industry, with most of the capacity either built in China or by Chinese-owned companies, FEOC only leaves a small percentage of global capacity that is not tied to a Chinese company.

“Everyone is still figuring this out. We’re helping a variety of companies to figure it out,” says Roselund. “There are those buyers who have a supply chain that comes from manufacturers with vertically integrated, domestic US production, who are now feeling much more confident that they can get their product, assuming that factories come online in the anticipated timeframes.

“A lot of the other suppliers are not looking like they’re going to be able to supply FEOC-compliant materials, either due to their own FEOC status or due to a relative shortage of non-FEOC cells.”

However, given the timeframe set in the OBBBA, projects seeking to be eligible for tax credits must start construction before 4 July 2026. As a result, there may not be many projects that will, in fact, require FEOC compliance, according to Hall.

“Our theory, and we’ll see if it plays out, is that the majority of procurements next year for solar will not have to worry about FEOC,” he says. “We see this narrow window between 1 January and 4 July, in which projects that commence construction in that time period will have to comply with FEOC. But everything that’s before that won’t have to comply with FEOC, because the law says it only goes into effect at the end of this year. Many options after that are probably foregoing the ITC anyway.”

For solar manufacturers building in the US, FEOC can also be an issue, especially if some of the companies involved in their construction have Chinese origins.

“A large number of the factories that were announced or were under construction or being built out have FEOC compliance issues, even in the US,” Hall explains. “And we don’t know whether or not we’ll see large-scale divestitures from Chinese companies. I’m not sure we’ll see as much as people think, because, again, this FEOC compliance window is only really six months. The real question for these companies is whether they think it makes sense to have a US factory in a post-ITC world.”

He adds that the reshoring of solar manufacturing to the US had two significant incentives from the IRA, which were both “jeopardised because of the OBBB”. The two incentives were the 45X tax credits for advanced manufacturing, which Hall highlights is a FEOC issue, and the other is the tax adder for developers and independent power producers. “If there’s no ITC, then there’s no adder. That means that there’s no hard economic driver to pay more for domestic content.”

Indeed, the advantage of using domestically made products lies in the tax advantages that companies get out of it. If, for some reason, a solar project cannot benefit from the tax credits that were included in the IRA, it could end up being more costly to use domestic modules than export them from another country, depending on how much tariffs that country is exposed to.

Roselund adds: “If you step out and look at this big picture, there are two things going on. One is that there are increasing tariffs, some of which are restrictively high on importing products from various geographies. The second, foreign entity of concern, does not work strictly according to geography. It works according to the ownership of the company.

“Between the two of these, you just really end up getting squeezed, particularly on the ingot and wafer side.

Safe harbour still happening despite change in rules

Although not tied to the OBBBA, it is still worth highlighting a policy change that affected the safe harbouring of solar projects that are aiming to secure tax credits before the deadlines set by the OBBBA.

Days after signing it into law, Donald Trump issued an executive order calling for new rules to tighten restrictions on renewable energy tax credits, which required a much harsher definition of the “beginning of construction” for solar and wind projects eligible for IRA tax credits.

Published in August 2025, the new safe harbouring rules tightened things for PV projects over 1.5MW by removing the 5% safe harbour provision and instead requiring a “Physical Work Test” to meet the “start of construction” threshold.

The test must confirm that “physical work of a significant nature” has begun on a project. According to the new guidance, this focuses on the nature of the work performed, rather than its cost or the amount itself.

Despite that negative impact on the solar industry, it still remains feasible to safe-harbour projects, according to Hall.

“It certainly was a negative for the industry, because it closed down a pathway that many companies were using. That being said, the majority of the activities that people were using to safe harbour are still viable. So it hasn’t been as big a hit as many feared it could be. We still see a lot of safe harbour activity happening.

“I’ve seen estimates of over 150GW of projects already safe-harboured. I can’t substantiate those estimates, but it doesn’t surprise me, given what we’re hearing from our IPP and developer clients,” Hall says.

Section 232: the one that has everyone’s attention

In July of this year, the US Department of Commerce (DoC) initiated an investigation into the imports of polysilicon and its derivatives under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962. Even though it’s still too early to know what the outcome of this investigation will be, this was the one policy that everyone was worried about at our PV CellTech USA conference in San Francisco in October 2025. Solar manufacturers and developers alike highlighted Section 232 before FEOC, as the policy that they were most worried about, or as some speakers put it, “keeping them awake”.

It was the same with industry experts PV Tech Power spoke with, and as Hall puts it: “This is the big one that’s on everybody’s radar right now.”

Roselund adds that “Section 232 gives the President the ability to impose trade remedies, including tariffs”.

The Coalition for a Prosperous America (CPA), a nonprofit organisation that focuses on US manufacturing policy, has called for a polysilicon tariff-rate quota that would affect the entire supply chain, and not only polysilicon.

In its comments sent to the DoC, it called for a “protective tariff” of US$0.20 per watt against all solar modules imported to the US, due to the country having sufficient domestic manufacturing capacity to cover the market.

As the organisation estimates this is not the case for ingots, wafers and solar cells, it established a different rate for each, with a US$0.10 per watt tariff for “over-quota imports of solar cells”, which it sets at 30GW. For ingots and wafers, it calls for a rate of US$0.07 per watt, while for polysilicon, it would be set at US$10 a kilogram with a of in-quota allocation limit of 40,000 metric tons of polysilicon. If the CPA proposition is adopted, this could have a significant impact on the US solar industry and the supply chain outside the US soil.

Regarding the proposal from the CPA, Roselund says: “That’s just one proposal. The truth is, no one is sure how this will end up working. We are taking the Coalition for Prosperous America’s proposal as our base case. And we’re expecting something like that.”

The industry consensus is that a decision on Section 232 regarding polysilicon and its derivatives is expected soon and will need to address some of the ongoing concerns. One of which, as mentioned earlier, is whether it will ultimately impose tariffs only on polysilicon or its derivatives up to the modules, as per the CPA’s proposal.

The other is which countries will be impacted by a possible tariff. The difference from AD/CVD cases, which are targeted to specific countries, is that Section 232 can target any and every country at once, which would put an end to the tactic used by Chinese manufacturers in Southeast Asia of moving manufacturing capacity from country to country to bypass previous AD/CVD rulings and avoid tariffs.

The current uncertainty regarding how Section 232 on polysilicon will end up looking has accelerated the procurement of modules, explains Hall. “Because there’s so much uncertainty as to where that will land and what the implications will be for the actual finished imported solar modules that aren’t using domestic poly, which is almost all of them.”

Houston, we have a wafer problem

Depending on the outcome of Section 232, this would create a much narrower bottleneck in the US supply chain, especially at the ingot and wafer level, according to Roselund. Currently, only one company, Corning, has begun producing ingots and wafers in the US, however, this will not be sufficient to supply the market’s needs.

“According to our estimates, Corning’s annual wafer capacity is approximately 2.5GW. Total cell capacity in the US is estimated to be 3GW, which is expected to increase significantly over the coming years. The gap is even more pronounced when compared to the estimated 35GW of modules being produced domestically,” says Joe Henessy, analyst at PV Tech Market Research.

The current policy landscape in the US puts Corning in a favourable position with its ingot and wafer manufacturing plants. If Section 232 ends up imposing tariffs on the entire supply chain, it would make it much easier for the company to further expand its capacity to meet domestic demand.

“You really need to pay attention to what the choke points are in the supply chain. I’m not worried about polysilicon. Yes, polysilicon from non-Chinese suppliers is more expensive, but there’s enough of it. What I’m worried about is wafer, and to a lesser degree, about cells,” says Roselund.

Roselund explains that there is a bottleneck in solar cell supply that is not subject to AD/CVD, while any cells not impacted by these duties come at a higher price. “Where are you going to get these cells from?” Roselund asks, adding that if procuring solar products was a very complex environment before, it has become even more complicated now.

“I used to say we’re in a very complex procurement environment. Well, now we’re in an even more complex procurement environment, and prices are going up. Since RE+ [in September], we have had a lot of suppliers go back and just retroactively change their prices.

“Because the supply is just getting that limited. There are concerns that this will cause projects to get cancelled,” concludes Roselund.