Researchers from the University of Cambridge have unlocked the mystery behind perovskite’s apparent tolerance of defects, with potentially huge implications for the future efficiency of solar PV modules.

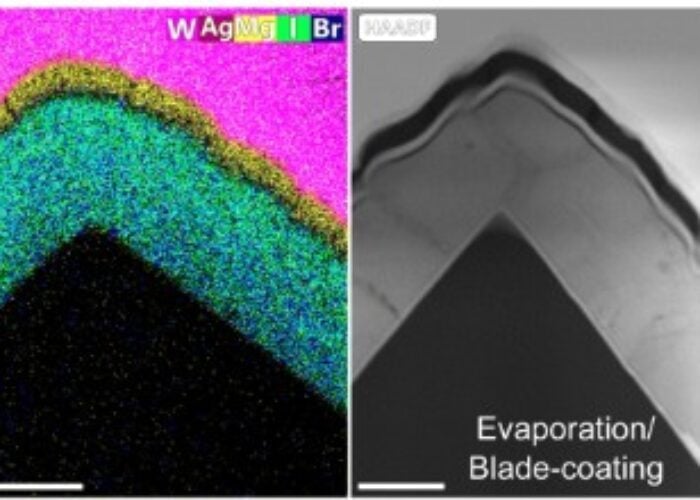

Using new microscopic methods to visualise perovskite materials and their seeming tolerance to defects in their structure ‘for the first time’, researchers concluded that two forms of disorder operate in parallel: electronic disorder and chemical disorder.

Unlock unlimited access for 12 whole months of distinctive global analysis

Photovoltaics International is now included.

- Regular insight and analysis of the industry’s biggest developments

- In-depth interviews with the industry’s leading figures

- Unlimited digital access to the PV Tech Power journal catalogue

- Unlimited digital access to the Photovoltaics International journal catalogue

- Access to more than 1,000 technical papers

- Discounts on Solar Media’s portfolio of events, in-person and virtual

It is the chemical disorder that mitigates the electronic disorder resulting from defects by funnelling the charge carriers away from such “traps”, researchers said.

“And what we’ve found is that the chemical disorder – the ‘good’ disorder in this case – mitigates the ‘bad’ disorder from the defects by funnelling the charge carriers away from these traps that they might otherwise get caught in,” said Kyle Frohna, a PhD student at Cambridge University and lead author on the study, which was published in the scientific journal Nature Nanotechnology.

So, despite the heterogeneity in the material structure leading to microscopic traps that reduce photovoltaic performance, perovskite still shows efficiency levels similar to polysilicon alternatives, even when damaged.

In fact, earlier research by the group showed that the disordered, messier structure can even increase the performance of perovskite materials.

The findings will enable the group and others in the field to further examine, explore and refine how perovskite cells are made in order to maximise module conversion efficiency.

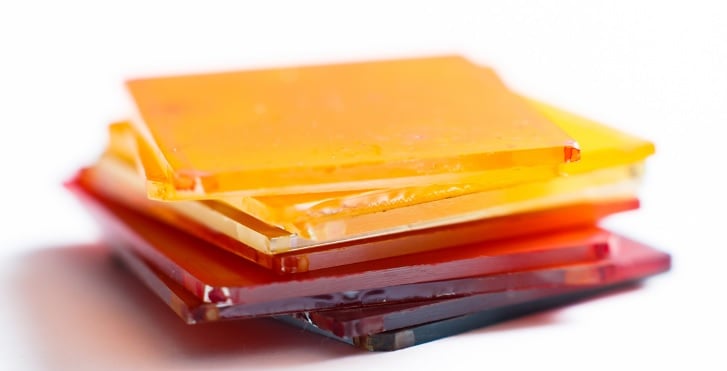

In the last decade, perovskite materials have emerged as a promising alternative to silicon based solar modules. The lead salts needed to make them are abundant and cheap, and they can be made in a liquid ink that is printed to produce a film of the material. In contrast, polysilicon-based modules require huge amounts of energy and time to produce the highly ordered wafer structure required.

As a result, many in the solar sector are assessing the potential application of perovskite materials, with the US Department of Energy funding research into the development of perovskites and companies such as Toshiba exploring how to get the most out of the material.

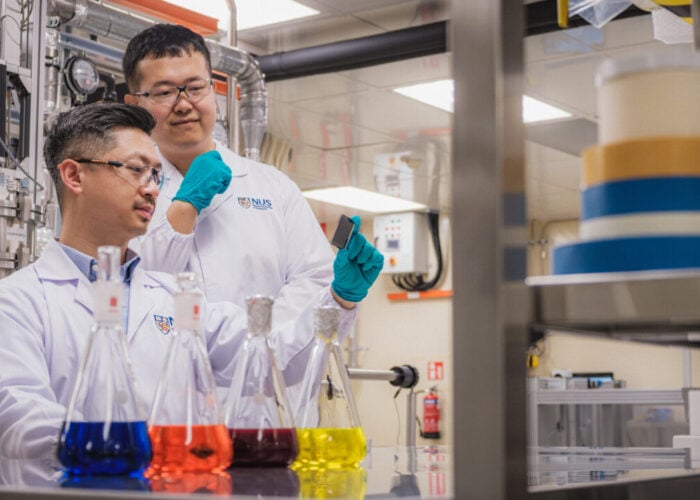

In collaboration with Cambridge University’s Cavendish Laboratory, the Diamond Light Source synchrotron facility in Didcot, England and the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology in Japan, the researchers used several different microscopic techniques to look at the same regions in the perovskite film to perform multimodal microscopy, which “is a fancy way of saying” looking at the same area with multiple different microscopes, said Frohna.

“This methodology enables new routes to optimise them at the nanoscale to, ultimately, perform better for a targeted application,” said Miguel Anaya, Royal Academy of Engineering research fellow at Cambridge’s department of Chemical Engineering and Biotechnology (CEB).

According to Sam Stranks, university assistant professor in Energy at CEB, the study “revealed blueprints for design of new semiconductors that may have similar attributes – where disorder can be exploited to tailor performance”.