The PV industry is set for a humbling 2025, with the current manufacturing downturn expected to extend well into 2026.

Representing the second major PV manufacturing downturn of the past 20 years, this period of the industry’s evolution could nonetheless create an ideal environment for PV technology to take its next logical step forward to the final chapter of the single-junction c-Si cell architecture era.

Unlock unlimited access for 12 whole months of distinctive global analysis

Photovoltaics International is now included.

- Regular insight and analysis of the industry’s biggest developments

- In-depth interviews with the industry’s leading figures

- Unlimited digital access to the PV Tech Power journal catalogue

- Unlimited digital access to the Photovoltaics International journal catalogue

- Access to more than 1,000 technical papers

- Discounts on Solar Media’s portfolio of events, in-person and virtual

In this article, I explain why capital expenditure (capex) has now become the accounting metric of choice—in the absence of tracking equipment suppliers’ book-to-bill numbers—in order to track the progress of the downturn and when it will become clear that a rebound is imminent.

Furthermore, I discuss why 2025 will be a year of maintenance and final-upgrade-spending, almost as a prerequisite for technology to make the likely move to back-contact cells, as this premium single-junction concept becomes the next mainstream offering as we move towards the end of the decade.

And finally, I dive into the archives and look at some of my commentary on the sector during the last downturn of 2012-2014, and do a side-by-side comparison of what happened then—and if there will be any parallels to draw upon when things start to pick up again (probably in 2026).

Why is capex so important to track?

When I started analysing the PV sector more than two decades ago, the industry had evolved from the shadows of more mature adjacent technologies, such as semiconductors and flat panel displays. Each of these had grown with a ‘Western’ (mainly Japanese, European and US based) equipment supply chain and most were public-listed entities.

Post ‘Enron’, accounting practices largely resulted in listed (mainly US) companies having to report revenues that were fully recognized and bookings (new order intake) that were ‘real’ and not artificially inflated.

This allowed one of the most useful forward-looking industry metrics to be tracked: the book-to-bill. This ratio—taken by dividing new bookings (order intake) by recognized revenues (shipped and recognized product)—could show if a sector was approaching a growth or decline phase. And it typically gave a 12-to-24 month window ahead of manufacturing spending (capex committed) eventually being reported. There is nothing more insightful than a book-to-bill ratio, from a leading indicator perspective, nor will there be in the future.

Between about 2010 to 2015, the PV book-to-bill was a relatively simple metric to track. Major equipment suppliers were Western and listed on stock exchanges. Many even reported revenues and bookings for newly-created solar PV business units, or (in the case of German tool suppliers) had evolved in a way that solar equipment activities were dominating their business.

Building up their cumulative book-to-bill—even across specific process tool types (such as Applied Materials’ screen printers)—could predict what would be happening in the PV manufacturing space 12-18 months out.

An entire ‘downturn’ phase could basically be mapped out, well ahead of the first ‘signs’ of this from the manufacturers themselves.

As such, the capex stated by the PV manufacturers became a lagging indicator, not the leading one that book-to-bill offered. This was due to capex generally being a metric that is stated retrospectively (often itself embedded in ‘investments’) and not essential to include in guidance. Even when capex is ‘guided’ in the PV industry, one often takes this with a pinch of salt.

The first PV downturn, during 2012-2014, was played out almost entirely in alignment with book-to-bill data accumulated during 2010 and 2011. So, why have I not been talking about the PV book-to-bill for the past two years? I explain this now.

Can the past help us now?

I went back and looked at media coverage from one of the press releases I wrote back in 2013, while I was working as a market analyst at a company called Solarbuzz. This was right in the middle of the previous PV manufacturing downturn. I was curious how early the last downturn had been seen, compared to the one happening now.

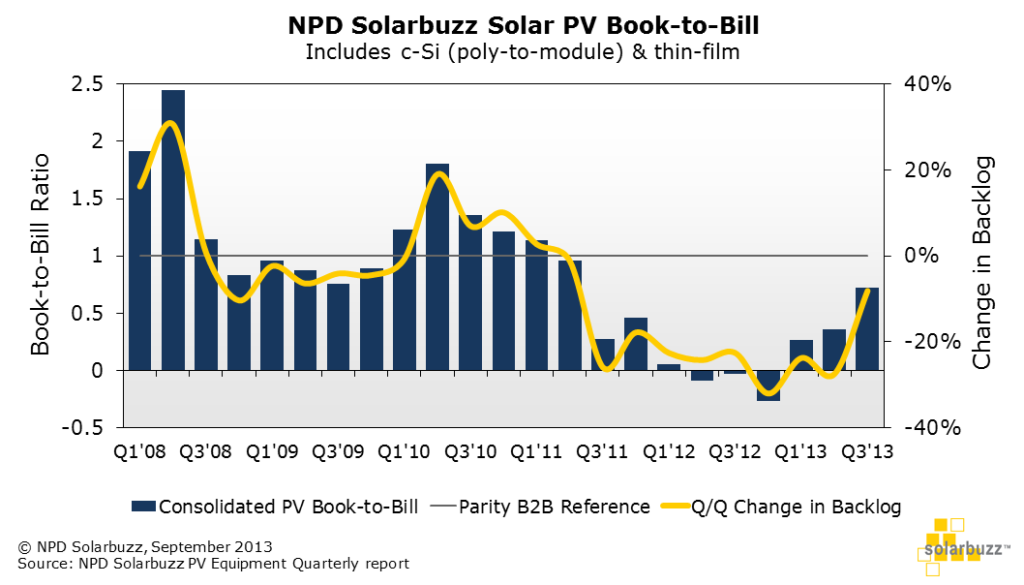

I remember collating the data and making the graphic in Figure 1. But more than anything, it gets me thinking: if only this type of analysis was possible today?

Just as a reference point in the graph above: the 2008/2009 cycle was actually an artificial effect arising from thin-film spending anomalies and was not related to any real manufacturing downturn.

A fascinating element to the graph is that the first signs of ‘green shoots’ (recovery from the sector downturn of 2012-2014) can be seen clearly as the book-to-bill starts to recover towards parity during 2013.

There is nothing as powerful as a meaningful book-to-bill analysis, when trying to forecast how an industry is set to play out two years in the future. The trick is knowing what numbers to use for company’s group revenues and bookings and how much of the market (specific equipment share) this equates to. Even with the Western suppliers of the past (mostly transparent!), this was challenging and almost a full-time occupation. But in the end, worth the time and very do-able. And incredibly useful.

Sadly, Western equipment suppliers lost to China

The downturn of 2012-2014 didn’t just kill off Western cell and module activity in the sector at the time, it also indirectly halted the ability to track the key book-to-bill metric.

As the PV sector rebound started in 2015, equipment-supply soon became the domain of the burgeoning Chinese PV eco-system, and many of these Chinese equipment suppliers were privately-held entities, bound at arms-length to the customers (wafer, cell and module suppliers) they were largely created to serve. Few were even shipping product outside China, as there was so little left of Western cell and module manufacturing after the last downturn.

For the past ten years, visibility on the ‘book’ part of the PV book-to-bill has become an invisible metric. Even after most of the Chinese equipment suppliers aspired to Chinese listings through IPOs, the outside world was left to scrutinise an accounting system that had no fiscal responsibility to report bookings (new order intake). And it would have been impossible even to know if these orders had any credence anyway.

Therefore, it simply became impossible to do a meaningful PV book-to-bill analysis. As such, capex became the go-to metric and this has been the case for the past decade.

While capex (as reported) is most often a retrospective number, the trick is to forecast capex better than the PV manufacturers themselves. (Most companies inflate capex guidance to look good, then reign it back in later. Or they simply have no idea what they will be spending six months down the line, so it a non-question in the first instance.)

In the rest of this article, I focus on what I think will happen going forward once the current downturn is over. And when green shoots may emerge to suggest that the sector is moving towards a collective and sustained period of profitability.

Green shoots likely during 2H’25

Let’s define what aspects of capex to look at. Capex in theory covers spending on new manufacturing facilities (fabs)—including buildings, infrastructure and production equipment—upgrade investments, and line maintenance.

However, when China began controlling the manufacturing segment as a whole, capex effectively became a combination of new equipment and maintenance spending. Building and upfront investment in China can be measured in pennies, typically a provincial quid-pro-quo arrangement, straight-line depreciated in the noise.

Therefore, over the past decade or so, capex has been somewhat binary: high when building new fabs and low when in maintenance mode.

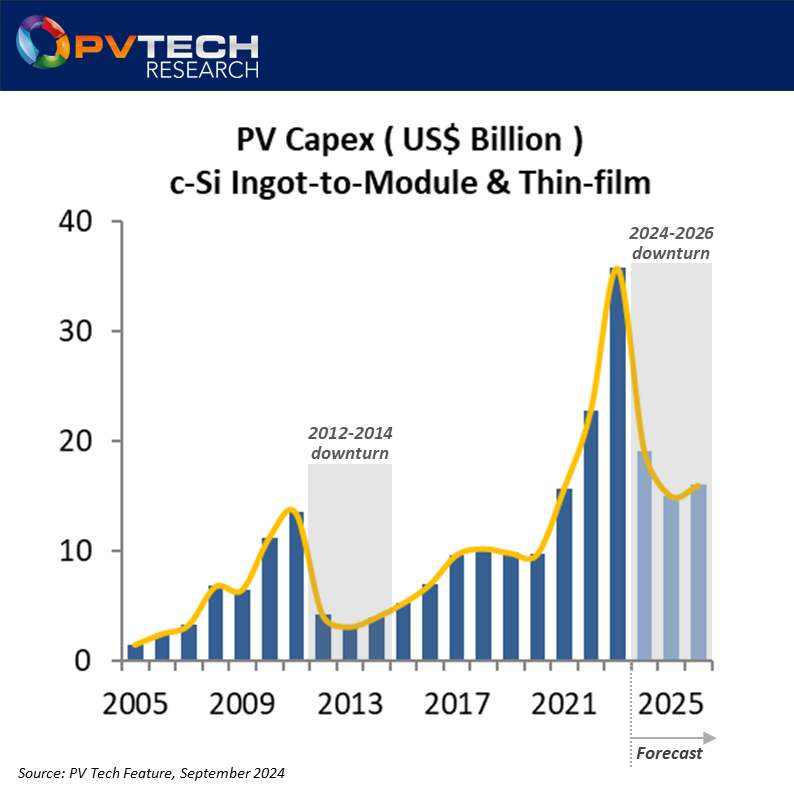

Despite these anomalies spanning the Western-to-China migration of PV equipment spending, the rise and fall of capex during the past downturn (2012-2014)—and the one today—are clear to see from annual capex data.

Before looking at the graph, remember that the other key issue in tracking capex is to work out what parts of the value-chain are meaningful to sum up. In this respect, polysilicon is the main anomaly, as the phasing of capex (even in China) is measured in years, not quarters.

Therefore, PV capex is best understood when looking at c-Si ingot-to-module spending, allowing thin-film contributions (a 100% First Solar phenomenon today) to be correctly incorporated.

The graphic below is, by default, a snapshot of the PV industry over the past 20 years. It covers PV capex from 2005 (actual) to 2026 (forecast).

A picture-that-is worth-a-thousand-words; one could narrate the history of the solar industry based solely on Figure 2 above.

The previous downturn of 2012 to 2014 was stimulated by two factors: thin-film investments from new entrants (mostly Western) and a wave of gigawatt-scale cell/module fab builds in China. The lure for most of the Chinese companies was to ship more modules to Europe, where feed-in-tariffs (FiTs) were still in force. Sound familiar?

As margins went negative through the value-chain in 2012, cash-preservation and maintenance-only capex allocations were the modus operandi for most of 2013 and 2014. Get ready for déjà vu.

The shake-out of sorts (not to be confused with consolidation) allowed the leading cell makers of the day to move technology from the mainstream offering up to 2013 (p-type multi back-surface-field cells) onto p-type mono substrates. This then opened up the road to changing back-surface-field (BSF) processing on the rear of the cells to allow passivated emitter and rear cell (PERC) concepts becoming a reality in manufacturing. PERC then made bifaciality an easy option for cell processing and module assembly.

In short: within a few years, mono ingot pulling (rods) had replaced multi ingot casting (bricks), and cell manufacturing was in the ideal place to make the natural shift from p-type to n-type. This started with a conventional passivated emitter rear totally diffused (PERT) process flow, before being upgraded to tunnel oxide passivated contact (widely abbreviated by this point to TOPCon).

Looking back, the ten years between the two downturns (2013 to 2023) can probably be considered as a golden age of technology progress in solar cell manufacturing. Not simply because of the efficiency benefits by moving from p-type multi BSF to n-type mono TOPCon, but through production equipment and factories, with nominal nameplate capacities and throughputs enabling 10-20GW expansions (almost exclusively in China) becoming the norm.

What went wrong this time around?

Back in November 2023, I wrote an article on PV Tech titled: ‘Can anything prevent a PV manufacturing downturn in 2024?‘ This largely set the scene for what was about to unfold during this year, and eight months into 2024, the forecast done back then is essentially correct. It was not particularly hard to see things were spiralling out of control a good year plus before then.

Looking again at Figure 2 above, it is overspending in the period 2021-2023 that has finally impacted the entire sector. No industry could sustain this level of mostly-unfounded exuberance. And while the impact is being felt mostly in China, it is a problem exclusively created by their own actions. Established companies in China blame the new entrants; the new entrants blame the overcapacity caused by their very actions—not to mention the established players all wanting to grow market-share versus each other! It’s a crazy way to run a five year plan, while destroying your own margins on offer from exports.

The past few years in China’s PV ecosystem have been bizarre, even by modern standards.

An ecosystem that seemed to have money growing on trees to support anyone (from any manufacturing background) to convince provisional lenders to build new wafer, cell and module fabs. The monstrous polysilicon expansion plans of the top five polysilicon producers in China coming online. The move from 5-10GW wafer or cell production to 20-50GW in a matter of months. The easy availability of production equipment from domestic suppliers, many only recently having completed IPOs itching to show revenue growth post-listing.

It is a recipe for disaster that is (of course) not confined to solar manufacturing, but one that had inevitability written all over it.

The impact of the over-investments is clear to see today. Margins reported mid-year by most Chinese PV manufacturers in the red, sometimes at horrific levels (often 30-50% loss making). Working capital non-existent. Mountains of debt building up. And few of these companies with anything else to sell but a loss-making wafer, cell or module.

And just to confuse things, we have the Chinese heterojunction drama that appears to have busted before it boomed.

But to get a better idea of how some of the leading manufacturers have fared so far in 2024, I return to a second feature I wrote at the back of 2023: ‘First Solar could be the only profitable volume PV module supplier in 2024‘.

This article fed off the previous cited link and is an ideal starting point to look at some of the tactics being used to keep margins positive while having to sell today with blended ASP’s at or around the 10c/W (USD) mark (excluding selling in the US of course).

‘Flexible integration’ once again rears its ugly head

For 20 years, I have been sceptical of almost all cost models propagated in PV circles. Mostly, I considered the methodology to be largely academic in nature; somewhat naïve as to how the real world worked. But essentially, not what happened in reality and specifically not how Chinese manufacturing entities operated to show profits on their books (even during a downturn).

Very few Chinese module suppliers have ever been fully vertically-integrated (at least including ingot pulling, wafer slicing, cell fabrication and module assembly). A small handful has the cited capacity to do this: but even these few companies rarely rely on having all key components made in-house.

Vertical integration should have benefits that make it a no-brainer: control of manufacturing quality, ownership of transparent supply-chains, the ability to control technology change, and in theory being able to keep overall production costs to a minimum. Well, this is the idea at least.

In reality, vertical integration (at least in China) can become a millstone in the wrong manufacturing environment. And this certainly comes to the fore during a downturn; especially when the mainstream technology of the day (TOPCon) has become somewhat ubiquitous in mainland China.

Essentially, what you get is a group of wafer and cell producers that are almost running as zombie companies in fire-sale mode. Or put another way, an abundance of wafers and cells on the market at cut-throat price levels.

This makes it an easy decision (at least for a financial controller) to stop trying to make the wafers or cells internally, but to buy them from outside. And this then becomes the most viable way to eke out any sort of profits, when sticking to a fully in-house vertical model would simply see costs exceed module sales prices.

I have noted on many occasions: making wafers and cells is a zero-sum game. Even a 50GW Chinese pure-play cell maker cannot exist in the sector long-term and will inevitably get squeezed during periods when module market pricing is low. For the leading module suppliers globally, having wafer and cell production in-house is not to make profits here, but to minimize costs to allow module sales margins to remain in positive territory.

Most of the leading Chinese module suppliers are now in strong wafer and cell outsource mode, with perhaps Canadian Solar the most prominent in this regard. How else can 15-20% gross margins be obtained when selling modules just north of 10c/W range?

It is a short-term tactic. Sooner or later, the fire sales die out. More worrying here today is that this approach is counter to the need for increased supply-chain scrutiny by module buyers (particularly in the US and across development portfolios relying on institutional investment). Traceability, sustainability and ESG are key metrics today. Relying on others to make the wafers and cells is not a good strategy in this regard.

What will 2025 look like and will 2026 be the rebound year?

The sub-title here is the big question today in the PV industry, not what 2024 looks like. This year has basically come and gone.

There is certainly going to be a huge fall in capex next year. Likely around the next reporting season (November/December 2024), the few Western-listed Chinese PV entities will get pushed (or at least should be prodded) about capex guidance for 2025. Maintenance-only will become the buzzword to look out for, not to mention any outstanding wafer and cell expansions being put on hold. The only company in the world that will probably be unaffected here is First Solar. To understand why, flip to the previous hyperlinked article above, written at the end of 2023.

Cash-preservation and cost-cutting will move to a different level next year. What this means for final module quality is anyone’s guess. With little prospect for module pricing (outside the US) even being in double figures, there is really not a plan B on the table. Polysilicon is highly unlikely to be in short supply next year, such is the determination of the leading China pack here to run newly built plants.

The sixty-four thousand dollar question for 2025 is simply: when will we see the first signs that the downturn is ending? For now, it is too early to contemplate this. It is likely things are still to get worse, before they get better. But as soon as signs emerge, hopefully I will be able to write here in a much more positive manner!