A recent note from investment bank Roth Capital highlighted the possibility of Section 232 on polysilicon being released imminently. Only a few weeks ago, during PV CellTech USA, many expected the investigation to take months (subscription required) as it wasn’t viewed as a pressing matter compared to Section 232 on semiconductors. However, the note from Roth Capital indicates otherwise, with a decision to be released by mid-November.

Ahead of its publication, several questions need to be understood quickly by any manufacturer or participant. The answer to these questions will affect the industry and the manufacturing landscape in the US.

Try Premium for just $1

- Full premium access for the first month at only $1

- Converts to an annual rate after 30 days unless cancelled

- Cancel anytime during the trial period

Premium Benefits

- Expert industry analysis and interviews

- Digital access to PV Tech Power journal

- Exclusive event discounts

Or get the full Premium subscription right away

Or continue reading this article for free

Will there be a different tariff for every region?

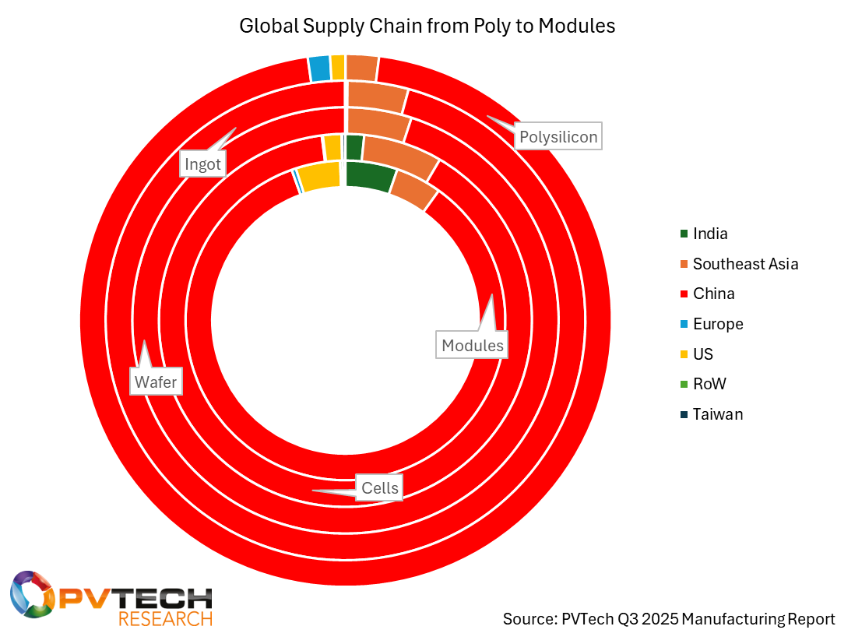

If this investigation aims to end the game of whack-a-mole that the US government has been playing with the Chinese manufacturers around Southeast Asia with the antidumping and countervailing duties (AD/CVD) investigations, then it would make sense that Chinese polysilicon becomes the most-tariffed.

After all, our data indicates that nearly 60% of the foreign modules entering the US originate in Southeast Asia. Thus, it would make the most sense to target them at the source. This would be bad news for most manufacturers that still source their polysilicon in China, but it would be great news for companies like OCI.

However, would that not replace one game of whack-a-mole with another? Instead of cells, would it be polysilicon? The answer is potentially, but if this policy aims to remove the Chinese monopoly over polysilicon, that would be a very effective way to do it.

The other option, which is much less likely, would be for all polysilicon entering the US from abroad to become heavily tariffed. While this would be ideal for internal US manufacturing, it would hurt short-term pricing throughout the supply chain and, more importantly, could slow future solar deployments.

What does that mean in the short term? In recent months, we have seen an increased demand for polysilicon, most notably Daqo New Energy (see chart below), suggesting that they are now managing to sell some of their inventory at a higher price. This indicates stockpiling in the US as market participants prepare for the decision. However, Section 232 can be retroactively applied, and the stockpiled quantity might not be safe.

What does this mean for supply chain management in the US?

Section 232 has the authority to target byproducts from the original raw material. Will this investigation target all the byproducts from polysilicon? The most likely answer is yes! It would be nonsensical if they only targeted polysilicon without the rest of the supply chain. It is, after all, a crucial piece in the puzzle of policies aimed at creating a downright domestic solar supply chain.

That poses the question of meeting the demand in the US. Our data indicates that the polysilicon-module gap in the US is approximately 18GW, excluding any other bottlenecks that exist around wafers and cells.

The US does not have enough supply to meet its demand and will not do so in the short term, as shown in the chart below. The US must procure the difference from external providers; thus, it would make sense to expect some quota of exempt polysilicon, and we would look for it when the decision is published.

The Coalition for a Prosperous America (CPA), a nonprofit organisation that focuses on US manufacturing policy, has called for a polysilicon tariff-rate quota that would affect the entire supply chain, and not only polysilicon.

In its comments sent to the Department of Commerce (DoC), it called for a “protective tariff” of US$0.20 per watt against all solar modules imported to the US, due to the country having sufficient domestic manufacturing capacity to cover the market. As the organisation estimates this is not the case for ingots, wafers and solar cells, it established a different rate for each, with a US$0.10 per watt tariff for “over-quota imports of solar cells”, which it sets at 30GW.

For ingots and wafers, it calls for a rate of US$0.07 per watt, while for polysilicon, it would be set at US$10 a kilogram with a limit of in-quota allocation of 40,000 metric tons of polysilicon.

The second part of the question concerns the transboundary nature of the polysilicon supply chain. Currently, the US has nearly zero wafer capacity (outside of that owned by Corning, which brought its plant online in the third quarter of this year). If you procure polysilicon in the US, you must ship it abroad to process it into wafers, cells and other products before bringing it back.

In the short term, anyone who wants to do that will have strict governance over their supply chain. Additionally, they might avoid one tariff (232) but expose themselves to another tariff (AD/CVD). It would simply be a question of which tariff is more palatable.

When will the tariffs come into effect?

The rules for a 232 investigation allow the relevant departments to complete their investigation, and another 90 days for the president to make policy decisions. However, the reality is that this timeline should be taken as indicative, and the investigation timelines rarely abide by that timeline.

To add to the confusion, we have been receiving varying estimates for the investigation’s date of completion. The measuring stick other analysts are using is the copper 232 investigation, which took an estimated 121 days. The pharmaceutical investigation was also expedited; although, we believe the US might delay the investigation results as it develops a more comprehensive pharmaceutical policy.

This highlights that the investigation’s findings may not be sufficient; they will also require a political will to translate them into policy. Nonetheless, the lack of mention of solar during the meeting between president Trump and president Xi would indicate that the investigation would proceed unimpeded by any political interference.

That said, we currently estimate that the investigation will be relatively brief. The facts are that there is a clear Chinese monopoly in the market, and for the US industry to compete on a fair and level playing field, it would need to protect its homegrown industry. These facts are not in dispute by any party; the only question in debate is how much an effective tariff would be that would help support local industries without damaging the rest of the supply chain.

Thus, we agree with many other analysts, most notably Roth Capital, that the tariffs should be ready in the next few weeks (if the government shutdown has not impacted the timeline).

To learn more about managing your supply chain risk in these times, please reach out to our market research team here. More to come on PV Tech and from PV Tech’s Market Research when the investigation’s decision is released.