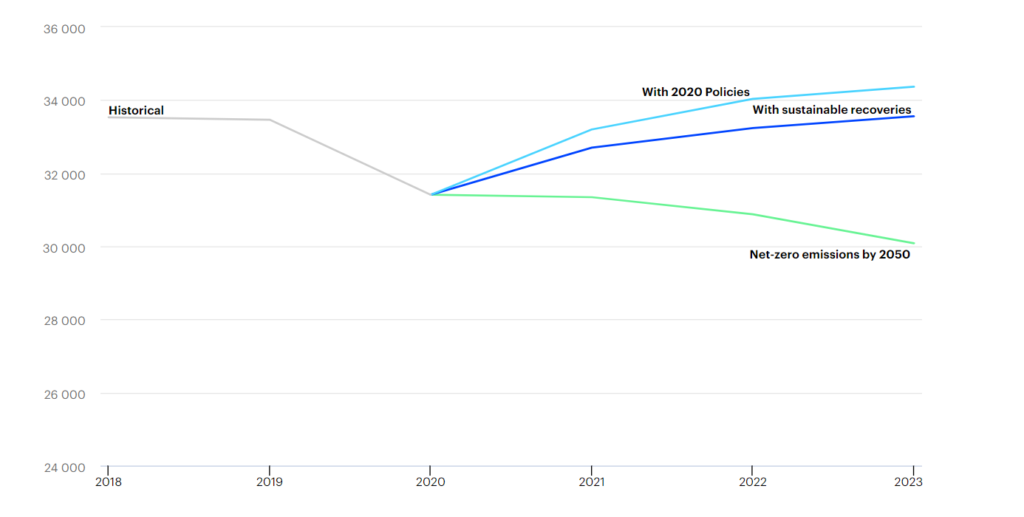

G20 member states are investing in fossil fuels at levels that make reaching Paris Climate goals unachievable, giving more than US$3.3 trillion in subsidies for coal, gas and fossil-fuel power from 2015-2019. Meanwhile, global greenhouse gas emissions are likely to rise to record levels in the next two years (34 gigatonnes in 2023) as governments fail to invest enough in green recovery programmes following the pandemic.

These stark warnings come from two reports released this week: BloombergNEF’s Climate Policy Factbook and the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) Sustainable Recovery Tracker. Taken together they make for grim reading, but may provide the ammunition needed to increase pressure on governments to invest more in renewables such as solar.

Unlock unlimited access for 12 whole months of distinctive global analysis

Photovoltaics International is now included.

- Regular insight and analysis of the industry’s biggest developments

- In-depth interviews with the industry’s leading figures

- Unlimited digital access to the PV Tech Power journal catalogue

- Unlimited digital access to the Photovoltaics International journal catalogue

- Access to more than 1,000 technical papers

- Discounts on Solar Media’s portfolio of events, in-person and virtual

What the reports say

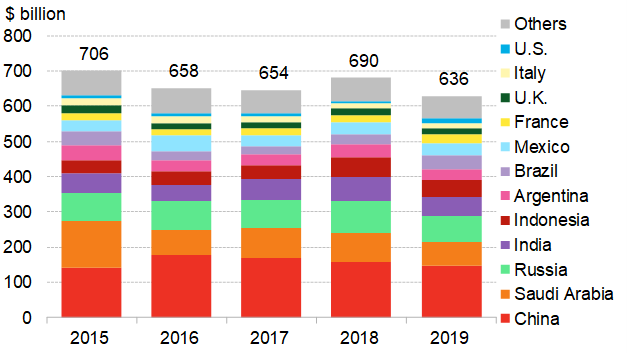

BloombergNEF’s report shows how G20 governments continue to provide substantial financial support for fossil-fuels, despite setting ambitious climate targets.

It details how the US$3.3 trillion spent on fossil fuels from 2015-2019 could fund 4,232GW of new solar power plants, which is more than 3.5 times the size of the current US electricity grid.

China, Saudi Arabia, Russia and India are the main culprits here, collectively investing more than half of the US$636 billion spent by all member states on fossil fuel support in 2019.

But support from these countries is decreasing over time, unlike the US, Canada and Australia who, from 2015-2019, have increased their support for fossil fuels, which the report said risked distorting prices and ‘locking-in’ long term carbon assets.

Crucially, the BloombergNEF report only covers up until 2019, before the onset of COVID-19. Since then, governments have failed to invest enough in their green recoveries, supporting fossil fuels at the same time and compounding the situation of the previous half decade.

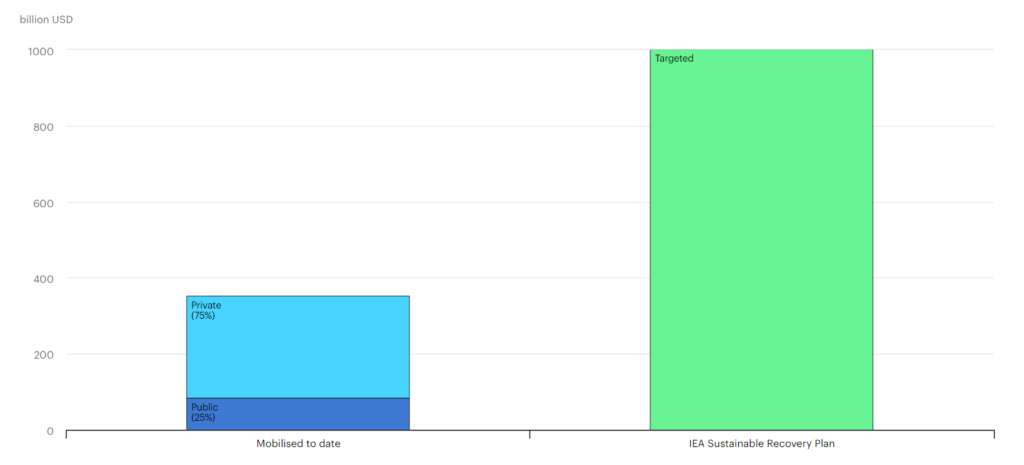

The IEA’s Sustainable Recovery Tracker showed that governments around the world have allocated only 2% of the total fiscal support of US$16 trillion on clean energy measures, which accounted for US$380 billion.

This spending has mostly been in the world’s 50 richest countries, particularly the G20, while poorer, developing nations are falling behind in their energy investments. With 90% of new emissions forecast to come from the developing world, there is a huge amount to be done to increase green investments in these countries.

Most policy measures thus far have sought to leverage private sector investment, with government spending representing only 25% of the total mobilised so far.

While new spending and policy initiatives will see an extra US$350 billion added over the next two years, this is still only 35% of the amount needed under the IEA’s Sustainable Recovery Plan to put the world on track for net zero emissions by 2050.

What it means

Not only are governments not spending enough on their green recoveries from COVID-19, but they have also demonstrated continued support for fossil fuels in the run up to, and emergence from, the pandemic. It would be reasonable to expect renewed pressure on governments from campaigners, companies and international bodies to match words with action when it comes to climate targets.

In the IEA’s Sustainable Recovery Plan, US$1 trillion of investments are needed each year, with governments contributing 30%. This presents a huge opportunity for private sector investment, supported by government policy, to fill the US$700 billion gap and move closer to hitting climate targets.

“It confirms what we’ve known for a long time: there is government money for energy,” Jenny Chase, head of solar analysis at BloombergNEF, told PV Tech. “Let’s hope to see it redirected to non-fossil energy.”

World leaders, and in particular those of the G20, are being urged to change course, removing financial support for fossil fuels and increasing both public and private sector investment in new technologies, as well as being more ambitious with their renewable energy targets.

Seeing as 75% of green investments are expected to come from the private sector over the next couple of years, companies should be looking at government incentives, policy mechanisms and industrial strategies carefully to see how they can expand their business operations.

The BNEF report points to three areas where immediate action is needed: phasing out support for fossil-fuels, putting a price on emissions and encouraging climate risk disclosure.

When it comes to pricing emissions, there have been mixed results so far. France and Germany have made good progress due to domestic policies and involvement in the EU Emissions Trading System, while other countries have either set the carbon price too low or the concessions for emitters too high.

It points to the US’s state level systems as covering less than one-tenth of national emissions, with relatively low prices on top. Some of the biggest polluters – Saudi Arabia, Russia and Brazil – are yet to even put a price on emissions. Given that pricing carbon emissions are a key means whereby organisations such as the UN and the EU are looking to reach net zero, greater scrutiny in this space may be forthcoming.

Moreover, the report called for greater climate risk assessment reporting so that financial institutions can better consider the impact of climate externalities and urged central banks to stress test their economies against changing climatic conditions, with some European banks already running their own assessments.

“We do know that government support for fossil fuels worsens the economics of renewables, particularly in places like Indonesia and Russia, and it would be better for everyone if governments got behind the transition in where they put their money,” said Chase.

Companies worldwide, but particularly in the G20 economies, will be able to use the findings of both reports to press their governments to step up their actions in line with their climate commitments. Armed with this data, and mapped against current emission trajectories, the case for significantly increased policy attention is overwhelming.

“Our hope is that G20 members take this report to heart, use its recommendations to hit their Paris Agreement targets, and show the world the health and economic benefits of building a resilient, sustainable global economy,” said Michael Bloomberg, founder of Bloomberg LP and the UN Secretary-General’s special envoy on climate ambition and solutions.