Researchers from the University of New South Wales (UNSW), Australia, have directly observed how silicon solar cells can self-repair UV damage under sunlight, offering new insights into degradation and lifetime performance.

The researchers have developed a microscopic, real-time monitoring method that reveals how crystalline silicon solar cells can self-repair following ultraviolet-induced damage, advancing fundamental understanding of photovoltaic material resilience under real-world operating conditions.

Try Premium for just $1

- Full premium access for the first month at only $1

- Converts to an annual rate after 30 days unless cancelled

- Cancel anytime during the trial period

Premium Benefits

- Expert industry analysis and interviews

- Digital access to PV Tech Power journal

- Exclusive event discounts

Or get the full Premium subscription right away

Or continue reading this article for free

The findings, published in Energy & Environmental Science, directly observe chemical bond reconfiguration during degradation and subsequent sunlight-driven recovery, a capability long inferred from electrical measurements but previously unresolved at the material level.

Solar cell performance is compromised by ultraviolet-induced degradation (UVID), a decline in efficiency caused by high-energy UV photons interacting with surface layers, particularly in high-efficiency silicon devices.

Traditional accelerated ageing tests expose cells to intense UV radiation to simulate years of outdoor exposure, but until now researchers lacked a non-destructive method to distinguish reversible changes from permanent structural damage.

UNSW’s research team used ultraviolet Raman spectroscopy to monitor chemical bond changes in operating cells exposed first to UV light and then to visible sunlight, enabling atomic-scale observation of damage and recovery processes without dismantling the device.

The experiments showed that UV exposure initially disrupts bonds involving hydrogen, silicon and boron near the cell surface, weakening passivation layers and reducing performance.

When the cells were subsequently exposed to visible light, however, the material partially returned to its original state as hydrogen atoms migrated back toward the surface and broken bonds reformed.

This confirmed that some forms of UVID are not permanent but instead involve reversible atomic-scale rearrangements driven by sunlight.

“This confirms that recovery is not just an electrical effect. The material itself is repairing at the atomic level,” said Dr Ziheng Liu, from UNSW’s School of Photovoltaic and Renewable Energy Engineering.

The ability to distinguish reversible degradation from permanent damage has important implications for module testing and reliability assessment. Current accelerated testing protocols may overestimate long-term performance losses by inducing degradation modes that would naturally self-heal under outdoor operating conditions.

The UNSW method provides a basis for refining test standards and improving the accuracy of lifetime predictions, particularly for high-efficiency silicon technologies.

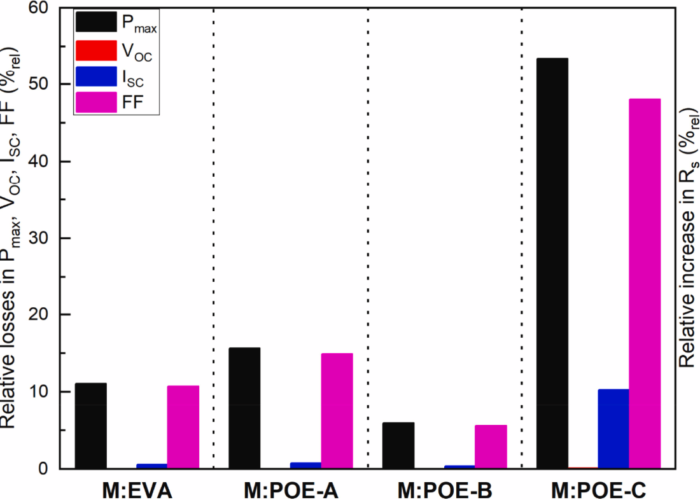

Material durability and degradation mechanisms have been a recurring focus of UNSW-led research reported by PV Tech. Previous work demonstrated how solar module encapsulant materials and construction quality significantly influence damp-heat performance, highlighting the interaction between material choice, manufacturing processes and environmental stressors.

Similarly, degradation pathways linked to passivation layer design remain a critical concern for advanced cell technologies. PV Tech reported on research earlier this month showing that thicker aluminium oxide layers are a dominant parameter limiting UVID in TOPCon solar cells, underlining how surface passivation design choices directly affect long-term stability under UV exposure.

The significance of these findings is reinforced by field performance data. UNSW recently revealed that up to one-fifth of deployed solar PV modules degrade around 1.5x faster than the industry average, underscoring the importance of understanding degradation mechanisms beyond nameplate specifications and laboratory efficiency metrics:

By directly linking atomic-scale chemical changes to macroscopic performance recovery, the UNSW study bridges a long-standing gap between laboratory ageing tests and real-world solar module behaviour.

The Energy Storage Summit Australia 2026 will be returning to Sydney on 18-19 March. It features keynote speeches and panel discussions on topics such as the Capacity Investment Scheme, long-duration energy storage, and BESS revenue streams. To secure your tickets and learn more about the event, please visit the official website.