Europe’s solar industry has endured a tough year, as the impacts of a longstanding oversupply crisis have combined with macroeconomic challenges and a faltering European manufacturing sector to cool interest in new solar developments at a time when climate goals loom larger than ever.

“Not only the solar industry, but the economy in Europe in 2024 was much weaker,” Christian Carraro, general manager of Europe at inverter manufacturer SolarEdge, tells PV Tech Premium. SolarEdge is just one of many companies to have endured financial struggles in 2024, with its own figures showing a loss of around US$1.81 billion in 2024, and a negative compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of -46.2% since 2022.

Unlock unlimited access for 12 whole months of distinctive global analysis

Photovoltaics International is now included.

- Regular insight and analysis of the industry’s biggest developments

- In-depth interviews with the industry’s leading figures

- Unlimited digital access to the PV Tech Power journal catalogue

- Unlimited digital access to the Photovoltaics International journal catalogue

- Access to more than 1,000 technical papers

- Discounts on Solar Media’s portfolio of events, in-person and virtual

These struggles are present in the manufacturing sector, where French PV startup Photowatt was closed down by EDF Renewables in January after failing to find a buyer. The same is true on the legislative front, where the European Solar Manufacturing Council (ESMC) has suggested that, in its current form, a draft of the European Commission’s Clean Industrial Deal will not alleviate the “extreme pressure from unfair Chinese competition”.

But, as Carraro says, these are not challenges unique to the solar sector. “I think the external factor of the economy – which is impacting interest rates [which are] quite high – means there is much less sense of urgency versus the electricity crises and the gas crisis,” he explains. “All this has had an impact; if you just look at the car industry or other consumer industries, they were down in 2024.”

In fact, while European solar struggled in 2024, Carraro suggests that these are the teething problems of a sector that has seen rapid growth in a challenging economic environment, rather than indications that European solar is a doomed industry. Looking ahead to 2025, he says that, despite these challenges, “we will see a growth, pushed specifically by commercial and industrial (C&I) and utility-scale”.

Beyond utility-scale

Carraro is most optimistic about Europe’s prospects for manufacturing in the distributed sectors.

“For specific niche applications – carports, agrivoltaics (agriPV), floating – we are seeing a lot of new niches popping up, that of course are going to increase in megawatt size,” says Carraro. “As always, in different industries, there is a difference between volume and quality. For sure, European production can find the space in all the quality-related marketplaces, and in all the niches.”

Carraro also draws a distinction between “technologies”, which are technically impressive but have not yet been deployed at scale, and “commodities”, which have more established supply chains. He suggests that Western European manufacturers, on the whole, are still producing “technologies”, rather than “commodities”.

“In general, Western European producers, especially when we look at technologies like inverters and batteries, [produce] technologies, not yet commodities,” says Carraro, who adds that European producers could be better served by focusing on technologies with niche applications, rather than trying to compete with China on sheer scale of production.

Carraro also suggests that these markets, while having considerable potential, have not yet reached the same level of maturity as utility-scale solar in Europe. He points to complex home energy systems in countries such as Italy, Germany and the UK as propositions that are attractive to people in these countries, but are less mature as the large-scale sector.

“People don’t buy a solar home system anymore [but] a solar system with a battery, maybe coupled with a heat pump and an EV charger,” says Carraro.

Oversupply drives a ‘clear supply chain issue’

When asked about the main challenges facing the European solar sector, Carraro is clear that oversupply remains the most important issue, saying there is a “clear supply chain issue” in Europe.

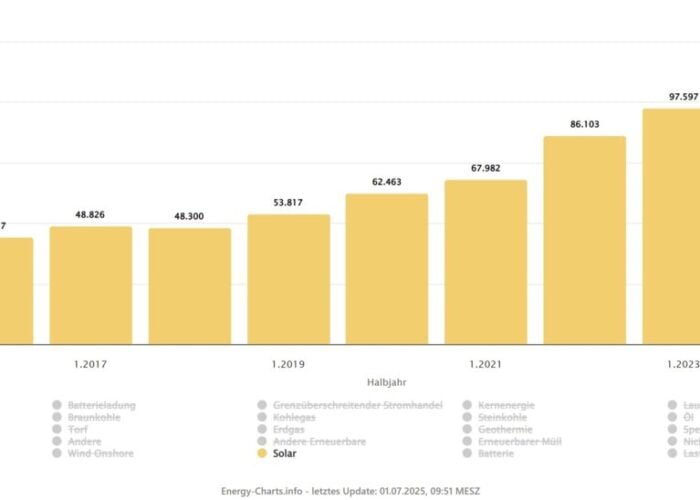

According to figures from EUPD Research, Europe imported around 100GW of solar modules from China alone, compared to annual installations of around 65GW in 2024. While Europe has increased its annual solar capacity additions each year from the 22GW added in 2020, this rate of installation has not been enough to eat into the backlog of modules that have been brought into the European market, but have yet to be connected to the continent’s grids.

“Over 2022, 2023 and early 2024 there was a big demand [for modules],” adds Carraro. “This very quick turnaround of the demand has resulted in big stocks and therefore price pressures.”

These price pressures are reflected in some of the more recent figures from pv.index, which cover module prices on a product-by-product and month-by-month basis in Europe. The end of 2024 brought to a close almost a year of consistent price drops across all types of PV modules, but, crucially, this did not dampen appetite in buying new products, with at least half of respondents to a pv.index survey saying they intended to buy more modules in the following months in each month of the year, save August.

“The demand is still very good,” agrees Carraro, suggesting that there is still appetite to acquire more modules in Europe. “If I do a comparison to the demand in 2022 and 2023, we still see a steady demand; but it’s not growing as exponentially as the industry was used to in the last two years, and it was preparing itself to meet that [exponential] demand.

“It’s a moment where, in general, all the different players need to adapt and resize for a market that is strong and probably will still grow, but it will grow at a much lower speed,” he continues. “That’s what we saw in the last two years, we saw 10-30% growth in specific markets, and this is honestly unhealthy when it’s combined with an unavailability of material.”

Greater legislative support

Carraro also notes that many of the broader macroeconomic headwinds have cooled interest in solar investment in Europe. Frustratingly, this is particularly true in the distributed sectors, the same ones that Carraro thinks ought to be the focus of European PV investment.

“[Macroeconomic challenges] have an impact in solar, especially residential – more than commercial – and that’s a trend we see,” says Carraro. “Homeowners became much more careful in investing money, and investing money in solar, and in some cases, even those who invested reduced their level of investment.”

He calls on lawmakers to deliver more supportive policies that will help encourage more investment in European solar manufacturing and deployment of products made on the continent.

“We have some unclarity on some policies,” he says. “For example, the Netherlands has changed its government and there have been a lot of uncertainties on the future of the net metering scheme in the Netherlands. This, of course, has a huge impact on the market and in the coming one or two years, this scheme will not be very effective. This is a policy issue.”

However, individual European governments have passed a range of policies regarding solar deployments and generation in the last year, from Italy banning agriPV to Germany curbing excess PV generation. In response to this somewhat scattershot policy approach, Carraro calls on the EU to implement more consistent legislation, but acknowledges the challenges associated with delivering such sweeping policies.

“I think the European government will have to do something otherwise manufacturing … will be almost dead,” says Carraro. “Because we are Europe [and] every country still has a lot of independence, it will take a lot of time.”