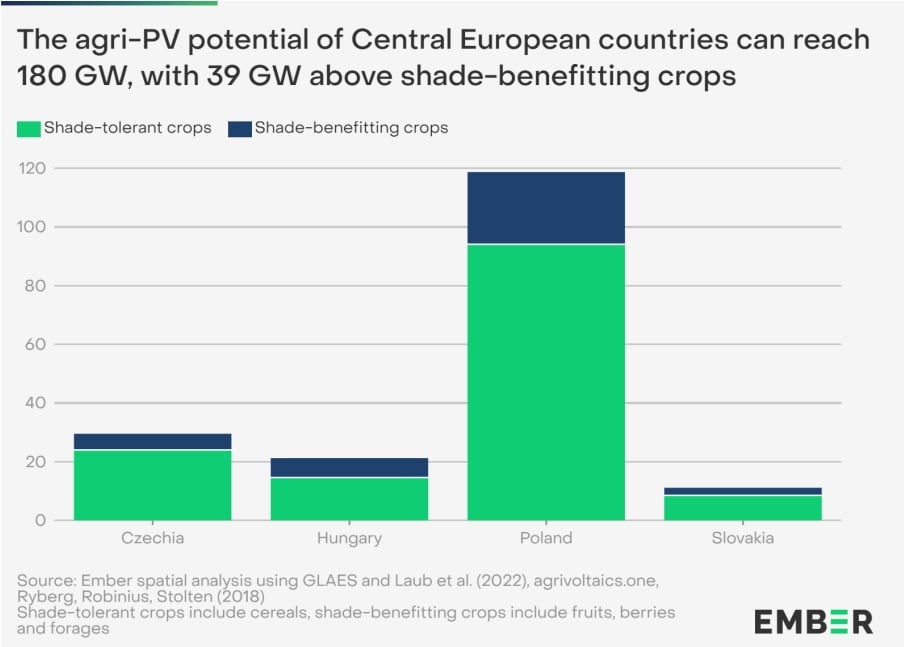

Countries in Central Europe have the potential to deploy up to 180GW of agrivoltaics (agriPV), according to energy think tank Ember.

In a report looking at four countries in Central Europe—Czechia, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia—Ember estimates that 39GW of agriPV could be deployed above shade-benefitting crops, such as berries, while an additional 141GW could be deployed through vertical solar panels placed between cereals.

Unlock unlimited access for 12 whole months of distinctive global analysis

Photovoltaics International is now included.

- Regular insight and analysis of the industry’s biggest developments

- In-depth interviews with the industry’s leading figures

- Unlimited digital access to the PV Tech Power journal catalogue

- Unlimited digital access to the Photovoltaics International journal catalogue

- Access to more than 1,000 technical papers

- Discounts on Solar Media’s portfolio of events, in-person and virtual

Between the four countries, the deployment of 180GW agriPV could nearly triple the region’s annual renewable electricity production, from 73TWh to 191TWh.

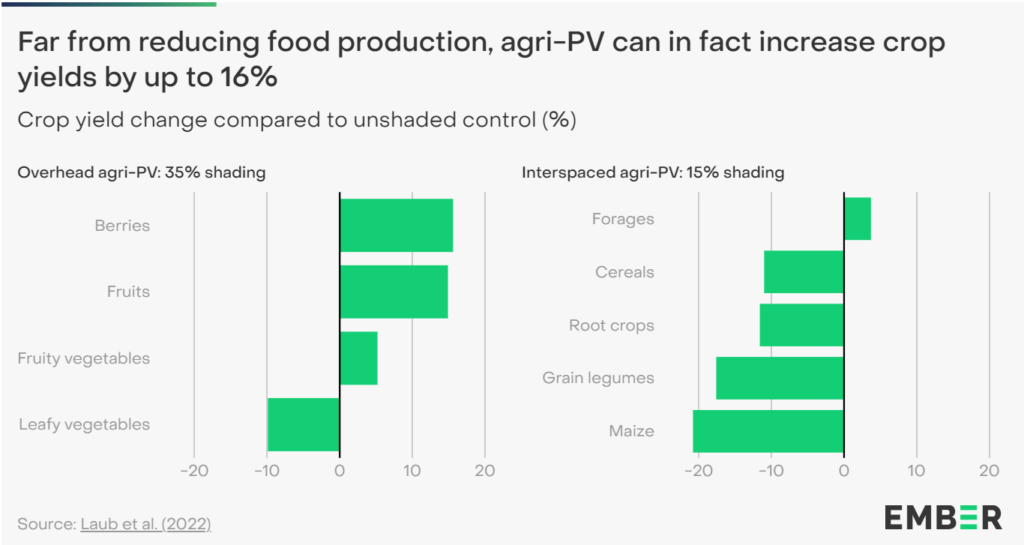

The combination of solar PV with agricultural land for food production also offers a benefit for the crops, with fruits and berries capable of increasing their yields by up to 16%.

Less shade-tolerant crops, such as wheat, could still achieve 80% or more of their typical yield. Despite the grain losses, farmers would still offset their revenues from the sale of electricity, an important aspect given that these four Central European countries represent 20% of the EU’s wheat production. Food production, including wheat, is at risk in these countries due to declining financial conditions for farmers, impacts of climate change and the volatility of fertiliser prices.

These benefits are in stark contrast with the recent ban on ground-mounted solar PV projects on agricultural land from the Italian government and the Ontario government, a Canadian province. In Italy, the ban was intended to preserve Italy’s productive agricultural land, a move which could cost the country up to €60 billion (US$66.5 billion) in lost private investment and tax revenues.

Legislation is key to agriPV deployment

Legislation is a key element to harness the potential and benefits of agriPV projects in Europe, which lacks an harmonised definition of what constitutes an agriPV project.

“This legislation needs to ensure that agricultural land retains its characteristics following any installation of agriPV systems so that it remains eligible for agricultural subsidies under the Common Agricultural Policy,” said the Ember report, regarding the legislation of agriPV.

Facilitating the deployment of agriPV would require efficient spatial planning, and easing permitting and grid connection procedures.

The report concludes that agriPV legislation should prioritise and incentivise continued food production, allowing farmers to benefit from agriPV systems for their crops and financial conditions.

Dr Paweł Czyżak, regional lead of Central Eastern Europe at Ember, said: “Far from reducing food production, agriPV actually increases yields for some crops. AgriPV combines the best of both worlds – electricity and food production, preserving precious land for agriculture, yet still enabling the energy transition to move forward, benefitting societies and economies. Governments in Czechia, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia can capitalise on the agriPV opportunity, increasing food and energy security while simultaneously combating the climate and cost of living crises.”

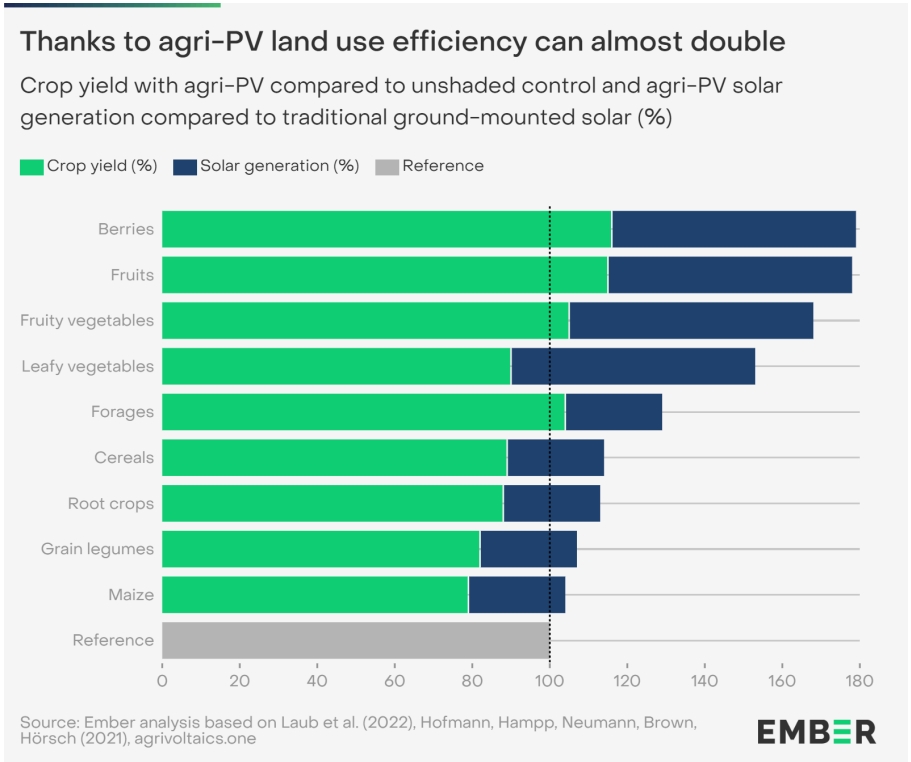

Moreover, the report highlights that the combined production of food and electricity increases the efficiency of land use compared to its use for only food or energy purposes.

Despite a ban on agriPV in Italy, interest in the technology throughout Europe remains high, as shown earlier this week with the 753MWp agriPV project in Germany from solar developer SUNfarming. The German developer partnered with energy services firm SPIE to design and install the substation for the project, which will span eight districts and 500 hectares in eastern Germany.

Ember’s report follows another report from the European Environmental Bureau (EEB), which highlighted that Europe could meet its net zero targets with “minimal” impact on land availability, through technologies such as agriPV.