Finlay Colville, head of market research at PV Tech, provides a detailed look at solar’s value chain, assesses the key motivators for supply chain scrutiny today and begs the question, just who makes what – and where – in today’s solar sector?

The PV industry is still awash with module ‘suppliers’. No one really knows the exact number; some come and go, some have mothballed fabs that never get restarted, some decide that simply being a distributor is a safer bet than trying to make money producing modules.

Unlock unlimited access for 12 whole months of distinctive global analysis

Photovoltaics International is now included.

- Regular insight and analysis of the industry’s biggest developments

- In-depth interviews with the industry’s leading figures

- Unlimited digital access to the PV Tech Power journal catalogue

- Unlimited digital access to the Photovoltaics International journal catalogue

- Access to more than 1,000 technical papers

- Discounts on Solar Media’s portfolio of events, in-person and virtual

The real number of active module suppliers is probably close to 100, but this is being very generous and counting 20-30 MW fabs as being of value to the sector as a whole.

When the Xinjiang question arose during 2021, there seemed to be a chronic kneejerk reaction globally, but mainly within the US and with brand-aware global corporates/utilities. They rushed to check in with a subset of these 100 module suppliers that the modules supplied did not contain polysilicon made in Xinjiang (or the raw material for polysilicon, metallurgical-grade silicon).

This article explains why the industry is fundamentally wrong in looking at this as simply a ‘tick-box’ exercise, and why the focus should be on a far more relevant issue: who is making what themselves, and where?

The article follows directly upon the key themes introduced through a series of extended pieces I have written on PV-Tech since the start of 2022, looking at why the industry is now in a production-led paradigm, how global module supply is concentrated across about 50 module suppliers of significance, how n-type technology adoption is likely to proceed within the industry over the next few years, and why module pricing is expected to remain at current levels for the next 18-24 months.

Module suppliers, module producers & PV manufacturers: what’s the difference?

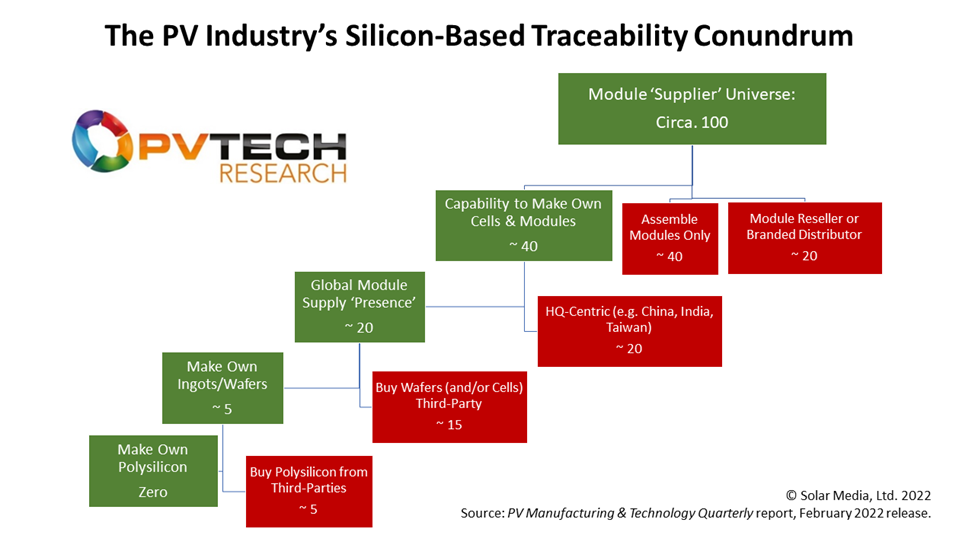

Let’s start with this estimated 100 PV module suppliers globally today, and why most of them have virtually no control over their upstream supply chains, technology roadmap, and bill of materials. I have tried to visualise this in the flow diagram below.

The first thing to realise is that the numbers are not exact; these change frequently in terms of how many module suppliers are making components in-house or actively shipping to overseas markets. Therefore, I have rounded the numbers to show the basic concept here.

At the top of the org. chart, the starting point is the circa. 100 module suppliers today that make up the industry (or 99%-plus of global shipments). First, I split this into three categories; non-producing distributors/resellers, those just assembling the module (i.e. buying in solar cells from other companies), and those that have (meaningful) in-house capacity to make both cells and modules.

The split here is about 20:40:40. Meaning that there are about 40 companies today that could supply a module within which the key component (solar cell) was made also by the same company (either within the same manufacturing facility or at a different site/region/country).

Going down the left hand side of the figure above, the next key segmentation (of these 40 cell/module producers) relates to their module supply ‘universe’; namely, is the company simply making product (cells and modules) in the same location that dominates final module shipments.

This is most prevalent today for some companies in China, Taiwan and India, but vastly weighted to Chinese versions of this PV business model. The reason this is important is that these companies tend not to have any access to overseas markets, and in many cases are frankly not interested in doing anything other than being a domestic-centric operation. They can largely be eliminated from any global module supplier short-list.

This brings us down to 20 module suppliers today that have in-house cell/module production capability and have a global (non-domestic) module supply footprint.

Next, I segment this grouping further, based on how many of these circa. 20 companies make their own ingots/wafers. This has the effect of ringfencing just five companies today that are in control of ingot-to-module production, and are module players on the global scale. The other 15 companies that were in the cell/module producing, global-module supplying category, buy wafers from other companies, mostly of course from within China.

Therefore, the list of module suppliers has now been reduced from about 100 to just five that can be said to be in control of in-house production from ingot pulling to module assembly. This alone probably will come as a surprise to many, but the next step is even more revealing.

None of these five module suppliers makes its own polysilicon. Each one is dependent on someone else making the one part of the value chain that is seeing short-term scrutiny today. Or – put another way – the PV industry does not have a global module supplier that is fully vertically-integrated, and that is a massive problem.

This is a problem that the industry alone (in particular the Chinese solar sector) has allowed to happen over the past 20 years. It is a problem that has impacted everyone else in the past 12 months (owing from polysilicon pricing). And it is a problem that has simply been brushed under the carpet as all-and-sundry across the value chain managed to convince themselves that the product they were buying (EPCs for modules, module makers for cells, cell makers for wafers, wafer producers for polysilicon) was a commoditised item.

The simple fact is that there is not a single global PV module supplier (of silicon-based modules) that is fully in control of all the key parts produced (poly, ingot, wafer, cell, module) of the modules sold to the end-market. In fact, from the above graphic, only a handful even make the wafer, and less than two dozen make their own solar cells.

Tell me this is not a problem.

Years of dismissing the value of in-house production

For years, PV module suppliers have treated the in-house production issue almost in a blasé manner; it doesn’t matter, fab-lite is the way ahead, all wafers and cells are the same, etc. Moreover, most of the companies that started to ramp up vertical integration (at least from ingot-to-module) some 10-20 years ago were highly vocal about how good a flexible supply chain was, allowing more margin to be made by selling in-house wafers and cells and buying cheaper versions from competitors for their own modules!

This rather carefree and dismissive approach to in-house quality control even extended to downstream operations of several Chinese module suppliers that had adjacent in-house business units developing and owning solar farms. Where possible, other modules would be used to build out plants, because they were cheaper. I could never get my head around that one, and what it implied for overall plant build quality if the main component of a solar farm (the panels) was being compromised.

In fact, for years, getting to the bottom of ‘who made what’ almost seemed like an undercover covert exercise. Companies with in-house wafer/cell/module capability stopped reporting any production numbers, and many today give barely more than a business unit revenue (of which module sales are just one part).

For years, I have felt almost a lone voice in the sector, writing about why I thought it was important to understand who made what. Mostly I suspect I sounded like a broken record. Nobody seemed to care.

The drive for this, from my side, was based mostly on quality control and technology roadmap ownership. How can you have any real grasp of module quality, if you are not in control of the key parts that make up the module? How can you have any form of technology roadmap if, for example, you only assemble a module?

I thought for years that the few companies that could make at least ingots/wafers and cells/modules might go vocal on this, and use it as a major differentiator in the market. But this did not even happen, and is probably because even these companies frequently outsource wafers, cells and modules (OEM supplied) when it suits them (mostly when a few margin points can be eked out at the end of the quarter).

Fast forward to 2022, and the industry is now obsessed with somehow getting a piece of paper that says the polysilicon was not made in Xinjiang. And this appears to be driving in-house auditing from a bill of materials standpoint.

How completely kneejerk and fundamentally missing the bigger picture.

Yes, there are plenty of reasons why the global sector needs to know this today. Getting visibility on the Xinjiang question is a massive deal for much of the western world. But how on earth has it taken this question to finally get people to ask who is really behind the production of components that go into a solar module?

How can the industry move forward in terms of auditing

Today, there is clearly a driver to have some kind of auditing that results in a box being ticked that says: this module does not contain polysilicon made in Xinjiang. It is only being done to tick a particular box today and for no other reason related to module quality and understanding who makes what.

Now, if you merge this with the fact that barely any global module suppliers are fully integrated back to wafers, far less polysilicon, then it does beg the question of how many module suppliers are in control of who makes what and where further up the value chain. How do these companies know what their cell makers are going to be doing in 12 months? Whose wafers will they be buying? What polysilicon will be used then?

The one saving grace for most of the downstream (module buyers and users) is that it would appear value chain auditing is only forward-looking and not retrospective. Cue a collective industry sigh of relief, for if it was to be retrospective then panic would surely unfold across the whole sector.

It makes sense that the starting point for any value chain auditing has to be from the basis of who is making what in a solar module. For example, once knowledge is gained if the company is a module-assembler only, or is likely to use cells or wafers in-house for its own modules, then it is possible to form a judgement if this module supplier will simply be buying whatever is available from cell makers in 12 months, far less have any say on where the polysilicon is coming from within China.

Knowing who makes what and where is probably also the best way to proceed, as it puts everyone in a good position for the next ‘event’ that occurs in the PV industry. Today, the two events impacting on this are the Xinjiang question and US import tariffs. No one knows what issues will be on the cards in 3-5 years, but it will almost certainly require knowledge of global PV manufacturing and supply-chains.

Currently, it is hard to know who is driving clarity on production and value chain auditing. We do know there is a strong desire for this, and increasingly global buyers of modules are raising this question to module suppliers. But the best way for this to work would be if the leading global module suppliers – starting with the five or so that make ingot-to-module – took a proactive position to ‘come clean’ on their own products. And not simply specific to Xinjiang polysilicon going into modules that get made in Southeast Asia and shipped to the US market. That is way too narrow and misses the big picture.

The leading five actually have an opportunity to put a clear divide between themselves and the other 95-or-so module suppliers in the industry today. Should that alone not be a driver? Sadly it would seem that everyone doing the bare minimum they need to do today, and no one is grabbing the current state of affairs as an opportunity to emerge as a leading supplier of choice in the future. But it would just need one of these five players to act on this, and the others would have to follow.

Could the industry ‘change’ to have fully-integrated c-Si module suppliers?

Well, this question is perhaps the big one to look at now, again!

The issue of full vertical integration (from polysilicon to module production) was flirted with briefly about 15-20 years ago. It quickly became unfashionable and no one has really been pushing this as a credible business model in the past 10 years.

However, there are a few signs that this model could emerge again, and create a new class of global module suppliers set to dominate the industry in the 2025-2030 period. This will be the focus on my next blog on PV Tech, with a working by-line currently of: Who will be the leading global PV module supplier in 2025? Watch out for the piece next week on PV Tech.

Finally, it should be remembered that there is one global module supplier that does have full control if its in-house components and does not rely upon polysilicon from China (or anywhere else for that matter). The company in question is of course First Solar. Not by choice, but by default, being the only thin-film producer in the sector today forces 100% in-house component and roadmap ownership. What a pity the other 200 companies that tried to set up thin-film fabs in the past 20 years are not in the mix today to force the silicon-based sector to smarten up its act.