Up to one-fifth of solar PV modules degrade 1.5 times faster than average, according to new research from the University of New South Wales in Australia.

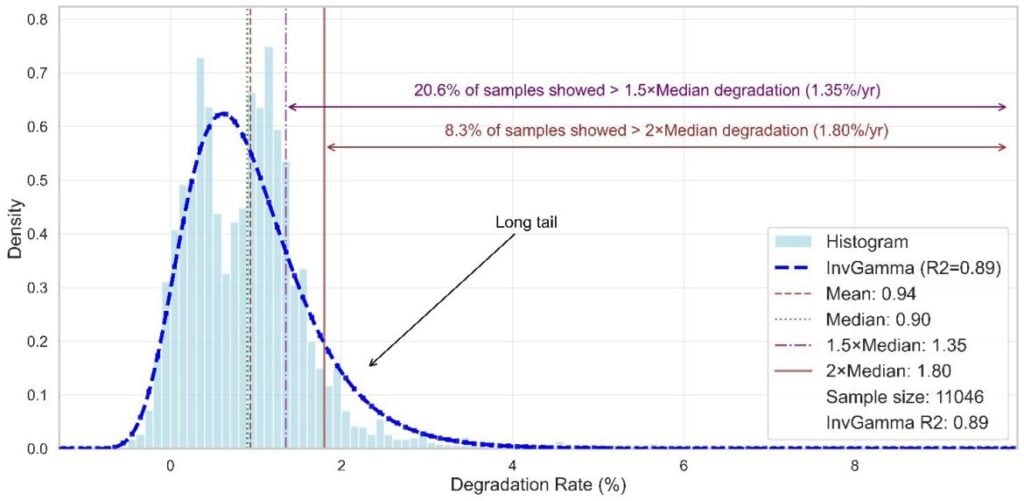

Researchers from the university analysed the performance of close to 11,000 PV modules, to investigate the reasons behind the ‘long tail’ in the probability distribution for module performance over time; this refers to the shape of the graph showing the frequency of the degradation rate of various solar panels.

Try Premium for just $1

- Full premium access for the first month at only $1

- Converts to an annual rate after 30 days unless cancelled

- Cancel anytime during the trial period

Premium Benefits

- Expert industry analysis and interviews

- Digital access to PV Tech Power journal

- Exclusive event discounts

Or get the full Premium subscription right away

Or continue reading this article for free

The graph, from UNSW PhD student Yang Tang, is included below and shows how the majority of panels assessed have a degradation rate of around 1%, but that the degradation rate of some modules could reach 4%, or even higher.

“For the entire dataset, we observed that system performance typically declines by around 0.9% per year,” said Tang. “However, our findings show extreme degradation rates in some of the systems. At least one in five systems degrade at least 1.5 times faster than this typical rate, and roughly one in 12 degrade twice as fast.

“This means that for some systems, their useful life could be closer to just 11 years. Or, in other words, they could lose about 45% of their output by the 25-year mark.”

The researchers identified three major reasons for some panels to have a much higher degradation rate than average. These include “interconnected failures”, where a problem with one component exposes other components to risks, multiplying the rate at which the module degrades; so-called “infant mortality”, where modules suffer from critical manufacturing defects not picked up during testing and cease functioning relatively early in their operating lives; and “minor flaws” that can lead to a sudden decline in performance at a random point in time.

However, the researchers also noted that the environmental conditions in which the modules were deployed did not have a significant impact on the ‘long tail phenomenon’, suggesting that the deployment of modules in more extreme environments, such as very hot climates, does not necessarily expose them to greater risk of failure.

“A subset of the data shows information specifically related to solar modules in very hot climates which we know causes higher degradation,” said Dr Shukla Poddar, another of the researchers.

“However, in other climates, when those hot regions are being excluded from the analysis, we see similar long-tail pattern in the probability distribution of performance degradation rate. This suggests that the issue is consistent regardless of where the panels are operating.”

‘So many different factors’ affect module performance

Poddar went on to suggest that there is a combination of “so many different factors” affecting module performance in the field, suggesting that assigning blame to a single cause, such as extreme weather, is perhaps too simplistic.

“But when they are actually operating in real-world conditions there are so many different factors coming into play, and those cascading failures can be very significant,” said Poddar. “So I think we need to start thinking about different testing standards which would help to ensure we have more resilient types of modules.”

Poddar’s comments, and the team’s research, comes as the solar industry’s testing houses report high rates of module failures. Last June, Kiwa PVEL’s Module Reliability Scorecard showed that five-sixths of modules had at least one failure in the testing process, a record figure that is up from two-thirds the year prior.

The UNSW researchers note that uncertainty regarding the long-term performance of solar modules “challenges the financial models that underpin the industry’s growth”, as module breakages and failures many years into a solar project’s operating life can interfere with the long-term electricity output and profit projections that are essential components of both the energy transition and the business case for solar investors and developers.

There is something of a vicious cycle at play too, where the longstanding manufacturing downturn in the global solar industry has encouraged manufacturers to cut costs in the module production process, according to Tristian Erion-Lorico, VP of sales and marketing at Kiwa PVEL, who spoke to PV Tech Premium last year.

“Stronger frames are necessary,” Erion-Lorico said. “It’s likely that [weaker frames] broke due to various cost-cutting measures related to both the glass quality and the frame quality.”

However, this has led to lower-quality glass and frames being used in modules, which could lead to more module breakages in the future, further eroding the profitability of the sector and prolonging the problem.