Researchers in Saudi Arabia have reported the “the first ever” successful damp-heat test of perovskite solar cells, which they claim has moved the technology closer towards commercial viability after it withstood 1,000 hours of harsh conditions and maintained a 95% efficiency.

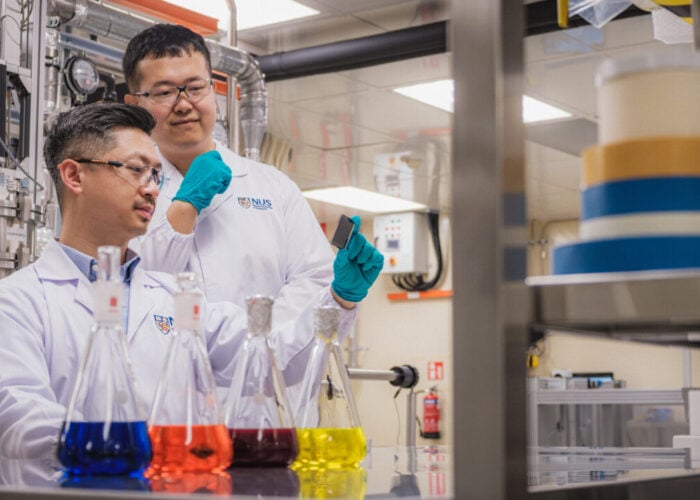

Scientists at King Abdullah University of Science & Technology (KAUST) in Saudi Arabia subjected the perovskite cells to a controlled environment of 85% humidity and 85 degrees Celsius in order to examine their ability to withstand real-world conditions such as corrosion and delamination.

Unlock unlimited access for 12 whole months of distinctive global analysis

Photovoltaics International is now included.

- Regular insight and analysis of the industry’s biggest developments

- In-depth interviews with the industry’s leading figures

- Unlimited digital access to the PV Tech Power journal catalogue

- Unlimited digital access to the Photovoltaics International journal catalogue

- Access to more than 1,000 technical papers

- Discounts on Solar Media’s portfolio of events, in-person and virtual

Test conditions were designed to replicate the effects of 25 to 30 years of use – the typical warranty period of crystalline-silicon solar modules – and were in line with commercialisation requirements, the researchers said.

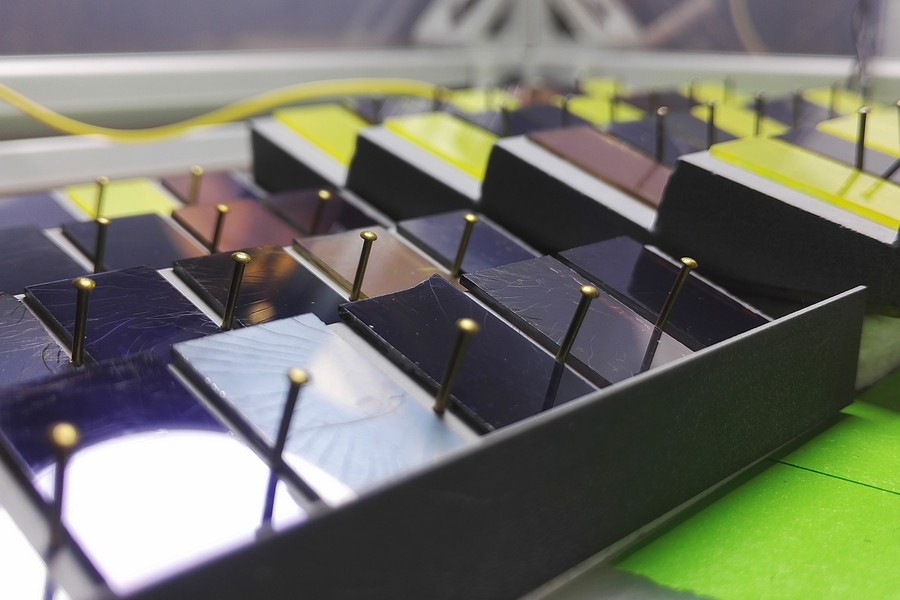

One of the issues of perovskite technology has been leakage caused by infiltration of atmospheric agents and a limited resilience against heat. Perovskite cells have proven extremely sensitive due to their thin film coating process, which makes them particular vulnerable to humidity.

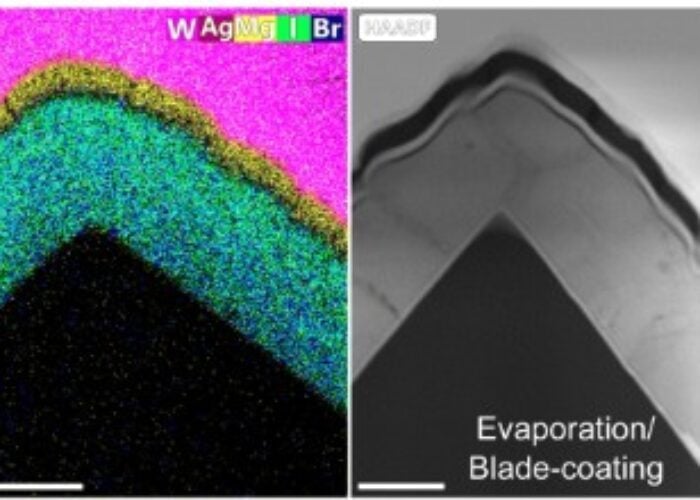

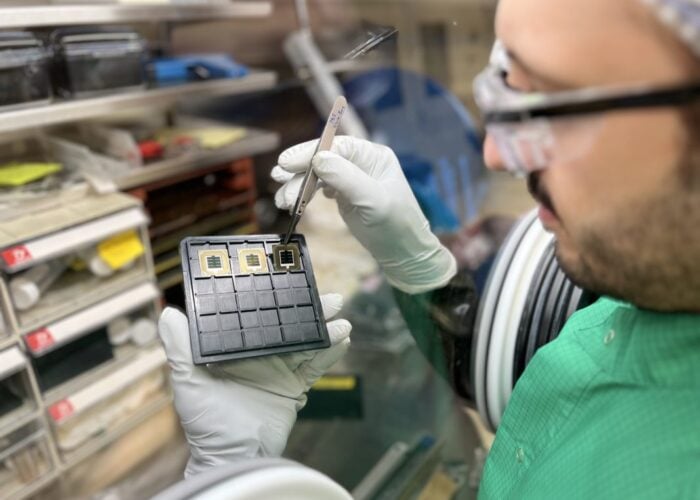

In response to these shortcomings, the researchers at KAUST introduced “2D-perovskite passivation layers” to simultaneously enhance the power conversion efficiencies and lifetime of the perovskite cells.

Unlike silicon wafers, perovskites can be coated directly on a glass substrate, using a precursor solution made with a solvent that gets crystallised into a solid state.

One advantage of this is that the precursor material can be made without the need for expensive facilities and energy-intensive environments of over 1,000 degrees, which is the case for silicon.

“It’s a very simple way to make solar cells,” said Professor Stefaan De Wolf, head of the PV laboratory at KAUST. “Also, while the optoelectronic properties are not unique, they are excellent. They’re on-par with very high-quality traditional semiconductors. That’s quite remarkable.”

The results follow more positive research on perovskite technology. In November last year, researchers from the University of Cambridge said they had “unlocked the mystery” behind perovskite’s apparent tolerance of defects and, back in May, scientists at the University of Bath and Imperial College London showed how the careful selection of layers within perovskite can prevent against degradation.

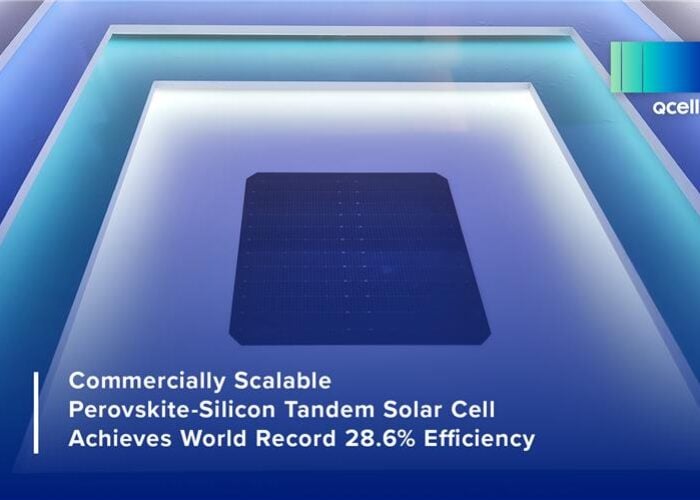

That said, Wolf did not believe perovskite cells were going to replace silicon-based cells anytime soon: “The market is silicon-based, and it will be silicon-based for the next 20 years at least,” he said, adding that KAUST was mainly focused on improving the performance of perovskite solar cells to advance more efficient “tandem” solutions pairing both traditional silicon and perovskites.

The KAUST study was led by postdoctoral fellow Randi Azmi.